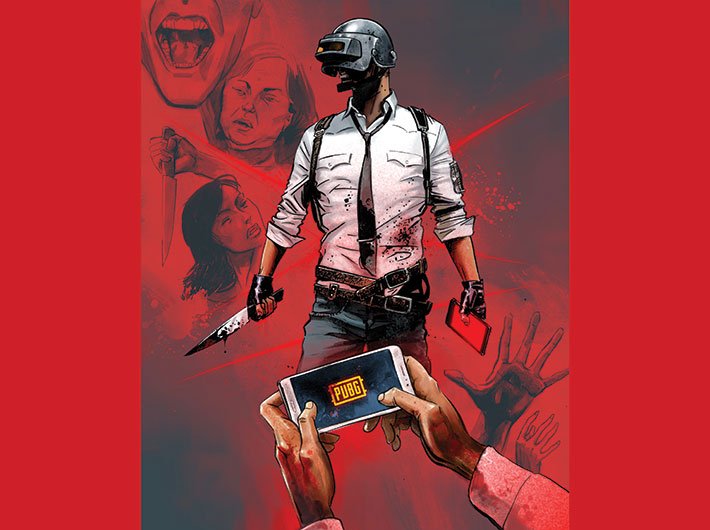

Violent virtual games are the new addiction, driving teenagers to alienation – and sometimes, violence

Hitlerkiller, a sniper, has landed in Georgopol, a city with many disused brick buildings and container depots hugging a bay in a U-shape. To survive for the next thirty minutes in the unknown land, he needs to find weapons, a motorcycle and a first-aid kit.

He will be attacked by unknown enemies. He will need to cross many hurdles.

Before all that, he needs to kill 99 people to win himself a chicken dinner.

After he shoots them down, racing against the ticking clock, the screen flashes: Winner Winner, Chicken Dinner!

Hitlerkiller, in real life, is Sarnaam Verma, 19, of Kishangarh village in south Delhi. All the time he plays PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG), a violent, interactive online game of survival pitting individuals and teams against each other on a shrinking map that squeezes them into conflict. The numbers on the timer swirl as players rattle and rumble through skirmishes and ambushes, hideouts and shootouts. Till there’s a last man/woman standing.

On October 10, Sarnaam stabbed his father, mother and sister to death. He’d apparently been angry with his parents. He had failed his Std XII board exam but obtained admission in a diploma course in civil engineering in a private institution in Gurgaon. His father Mithilesh, 44, a construction contractor, had wanted him to eventually take over the business. His mother, Siya, was a homemaker. His sister, Neha, was 16. The young man stabbed his father first, eight times. When his mother intervened on hearing the commotion, he stabbed her 18 times. Then he rushed to his sister’s room. She was found strangled and with seven stab wounds.

Sarnaam, also known as Suraj, told investigators he hated his family because they always faulted him and praised his sister. He claims he failed his Std XII board exam because his father pressed him into supervising the construction of the building they live in. He was thrashed on occasion. Blamed for poor grades and wasting his time on online gaming and bad company. He had rebelled by hiring a room in nearby Mehrauli, where he and his friends would hang out, watching TV, drinking beer, smoking hookah. And playing online games for hours, sometimes from 7 am to 6 pm. He had recently broken up with a girl.

“We literally worshipped him,” says one of Sarnaam’s friends, who all admire his exploits on PUBG. They are on a WhatsApp group of 11 for coordinating activities, meet-ups, game challenges and tournaments. Many of them have bunked school or college to hang out at Sarnaam’s room in Mehrauli.

Kishangarh village is contiguous with Mehrauli and lies near Vasant Kunj in south Delhi. Like most urban villages, it houses many original farmer inhabitants who have turned landlords of a different kind, renting out flats to migrants, students, nurses and paramedics at the nearby Fortis hospital, first-time jobbers, Africans, patients (or medical tourists) from Iran, Iraq, the Gulf. Many migrants have also made it their home, buying flats where the only source of light is from the large front window opening on narrow street. Shops line the streets, and above them rise the apartments with cramped parking space and dark entries and staircases.

Mithilesh raised one such building, about 18 years ago, after coming to Delhi from Kannauj, in Uttar Pradesh, to work as a civil engineer and building contractor. He had named the building after his wife. They refurbished the building two years ago, and Sarnaam had been asked to oversee part of the work. The Vermas had a steady rental income from the apartments, and occupied one of them, a 3BHK. Those who know the family say the boy thought he needn’t study or work hard because they were well-off.

“We may be shocked by the reason for these murders, but it’s the truth and the changing face of the Indian family,” says Devendra Arya, deputy commissioner of police (DCP), southwest Delhi. “The way his parents treated him is normal in India. The boy flunked Std XII, spent the entire day on the phone. He shows no sign of remorse.”

Arya does not believe Sarnaam may have psychological problems. He thinks Sarnaam is an unconscionable liar, mature enough to know the consequences of his actions. He says Sarnaam’s friends had no idea of his tiffs with his parents, his struggles with his studies, or his background. “He was a stud among his friends, had a rented room, drank beer, smoked and had a girlfriend,” he says.

***

Pavan Duggal, a cyber law expert, calls games such as PUBG “hunger games”. Clash of Clans, H1Z1, King of the Kill, The Culling, Counterstrike, Contra – they all throw players into virtual worlds where they must compete to kill and kill to survive till there’s no one left but the winner. There are points to accumulate, prizes to win, such as the chicken dinner, all totted up against the bodies hitting the floor, the structures destroyed. Privileges such as weapons of various grades and destructive power or how a player appears to other players are awarded against points won at each stage of the game. These features make for an addictive hunger.

While it is not clearly established whether addiction to violent virtual games predicates violent behaviour by players in real life, porn addiction has been widely acknowledged as affecting the sex lives of men and women alike. Similar effects, such as loss of touch with reality, and mimetic behaviour might be expected from addiction to violent games, along with a sense of alienation. High stress levels, sleeplessness and inability to concentrate is common among game addicts. So is addiction to alcohol, tobacco, marijuana or other drugs, especially ‘uppers’ that enhance alertness.

“These games give players a sudden adrenaline rush,” says Dr KK Aggarwal, a former chief of the Indian Medical Association (IMA). “The mainstream view of gaming has become less curmudgeonly. Parents no longer think of online games as a horrible evil that will corrupt their children.” He goes so far as to call the games hypnotic, and says that if an individual is guided and passively hypnotised by the explicitly violent game, he will become the character and act out the violence of the game in real life.

Dr Kamna Chibber, head of mental health and behavioural sciences at Fortis Healthcare, blames the addiction to online games to the change in societal structure in recent years. “Family members are away on the computer or the internet...there’s an empty space that should be filled by outdoor games or in time spent with family members, and this empty space is taken up by online games. Parents are constantly pushing children to achieve perfection, ignoring the fact that natural development occurs through the sharing of health criticism, not by deprivation or scolding. The appreciation that children crave from their parents is given to them by the games. ‘Great job!’, ‘You’ve won!’, ‘You’ve got so many points!’ Even if they lose, they can start all over again. Such activity boosts serotonin levels in children. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that makes you feel happy and relaxed, and this too fuels addiction.”

The addiction cuts across classes. “It’s not about the lower or the middle or the upper middle class,” says Dr Mansi Wadhwa, a psychologist. “At my clinic in Greater Kailash-I, every month I get three-four parents who complain about the behaviour of their children. But many of them do not want to discuss the problem with their children or want a professional consultation. The problem requires a holistic approach, reworking how the family structure works and how the internet is used.”

Parents, teachers, counsellors and students need to come together to help prevent the problem and draw addicts out of the spell of violent virtual games. Dr Chibber does not go so far as to blame gaming for violence: they can only be one of the reasons, parents’ attitudes, peer groups, home environment have a role too. Curbing internet usage can help. Says Neha Singh Malan, a teacher at Greenfield Public School, “In schools, the use of technology is largely monitored. But at home, the child is free to spend long hours on the net, with parents often taking pride that they know nothing about using the internet while their child is an expert. They even consider it okay that the child plays 20 games at a stretch online. They forget that sometimes it’s best for the child to study from books, without going online.”

***

Cyber crime advocate Duggal says India doesn’t have laws to regulate online games, with the Information and Technology (IT) Act 2000 leaving those aspects untouched. “India has begun to see the violence caused by the online games. The IT Act 2000 was passed without discussion in both houses of parliament. It is silent on regulating online games that force a player to do self-harm or incite violent behaviour. The police too seem reluctant to register cases as there’s no telling who to name as the accused. There are games that tell you how to rape or kill someone...and the dark net is taking away our right to access safe online space. It’s high time we have a gaming law,” he says.

Talish Ray, another legal expert, however, feels parents and schools need to step in and teach children how to use technology and information from the net without getting trapped in behavioural problems like addiction to games or online gambling. “Our IT laws are pretty rudimentary. In some cases, the penal code is applicable, such as when someone incites someone to violence, but that’s tough to prove in terms of gaming...who will you hold guilty?” he asks. “Regulating gaming legally is challenging, not just in India but all over the world. Most of these games come up with guidelines and clearly mention a safe age to play. But they are available for anyone who cares to play, however young. As a society, we’re failing because our kids are not able to differentiate between online and offline worlds. Isn’t that scary? It’s high time, school and parents need to address the issue and include the topic in the curriculum.”

He offers an analogy. “There are fire hazards in every home. But we don’t hear every day of children dying in fire accidents at home. This is because from an early age, it’s dinned into their ears that they must not play with fire, matchboxes, electrical mains and so on. Similarly with technology: children must be taught to access it, and use it with care.”

In June 2018, the World Health Organisation (WHO) added gaming disorder to its International Classification of Diseases. The condition is still sporadic, with less than three percent of all gamers believed to be affected. But it’s a clear and present danger, as Sarnaam’s story shows. India has the third largest base of internet users. The online gaming industry is estimated to be the highest growth segment in media and entertainment, with projected average growth rate of 27.5 percent between 2016 and 2020, compared to the overall industry’s 11.6 percent for the same period, according to a March 2018 report by FICCI and Ernst & Young. Its revenues are already more than the radio and music industry.

***

At Duggal’s home, a battle of a different sort has been fought and won.

He remembers how his 10-year-old son would be embittered and frustrated: the 15-year-old daughter would either not allow the boy to play car-racing games online or would let him play and defeat him mercilessly. There would be whining and shouting and sibling rivalry playing out in all its forms. “And whether they played or not, they’d forever be unhappy!” he says. “Addicted to them, they’d play and lose, feeling frustrated. And if they kept off the games, they’d again feel bad, because it was a craving they could not control.”

His solution: No video games, no use of the internet during weekends. Time was to allotted for friends, family, outings, cooking, playing offline games. And no phones.

“I started to limit the use of the internet during weekends in 2013 for my kids and results were quite clear. They start appreciating things around them and eagerly wait for weekends. In 2014, my daughter chose to lose in the same car racing game for the sake of her younger brother,” he says. “That doesn’t mean she’s not doing well. But she understands that the virtual world is not the real world.”

deexa@governancenow.com

(The article appears in November 30, 2018 edition)