This story may sound apocryphal but it was recounted by LK Advani in one of his casual conversations. Talking about Morarji Desai, he said that despite his idiosyncrasies, he was a man of impeccable integrity. To buttress his point Advani recalled this incident: After the Janata Party formed the government with Desai as its head in 1977, there was a by-election and the party wanted to field a candidate with shady background to ensure victory. When Desai heard of the choice, he raised objection on his credentials. “He alone can win this election for us; otherwise we will lose,” Desai’s colleagues told him. Desai quipped, “In that case, let’s not win this election.”

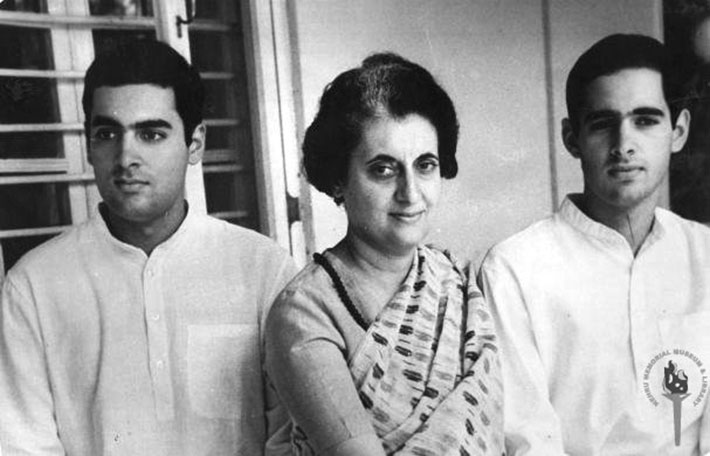

No doubt, Desai was perhaps the last among the sentinels of Gandhianism that eminently prized values and sanctity over buccaneerism in public life. His contempt for criminality had a background. His predecessor Indira Gandhi was justifiably accused of degenerating public life to such an extent that a criminalised band of lumpen under the leadership of her son Sanjay Gandhi practically monopolised the state. Desai was the complete antithesis of the prevailing political culture. He was probably the last.

Courtesy: Nehru Memorial Museum and Library

Courtesy: Nehru Memorial Museum and Library

What a fall from that point on: India even had the ignominy of a shady stockbroker alleging that he delivered cash in a suitcase to the house of prime minister P V Narasimha Rao, which the latter was hard-pressed to disprove. This was ominously symbolic: the prime minister who ushered in big-ticket liberalisation hobnobbing with a scamster.

In the 1980s, I came across the first instance of the impunity with which gangsters rule the roost – in Lucknow, in this case. That was an ordinary evening when I was cycling down the ‘monkey bridge’ and reached near the KD Singh Babu stadium when gunshots broke the serenity. A band of criminals in an open Jeep was chasing a car which carried one of the dreaded gang leaders of those times – Gurubux Singh Bakshi. Though Bakshi was hit by the bullet, his driver smartly carried him to the adjacent residence of the district magistrate. The criminals stopped at that and Bakshi’s life was saved.

Bakshi was not an ordinary gang leader. His political mentors included the redoubtable Hemvati Nandan Bahuguna, once a UP chief minister from the Congress and later an important member of the Janata Party. But then, the political class’s fascination for crime had little to do with ideology anymore. Those swearing by socialism across the political spectrum, from the communists to the Congress, tended to see underworld operators as new age Robin Hoods.

Consider the story of Hari Shankar Tiwari, the most dreaded Brahmin gang-lord of eastern UP and you would know the influence powerful warlords gradually came to wield on the Indian polity, particularly in north India. Tiwari was to contest assembly polls from Chillupar, in Gorakhpur district in the late eighties. He was in jail, but that was not to prove a handicap. An independent candidate, Tiwari is credited as the first candidate to win a major election in India from behind bars.

Tiwari is thus one of the pioneers of the trend of criminals turning into politicians. He is the prototype of the tribe now known as bahubalis. Consider the facts. Firstly, he had 30-odd criminal cases (including for murder) against him. Secondly, he was more successful than many seasoned politicians as he went on to win five more elections, representing Chillupar in the UP assembly for more than 20 years (his son is the MLA today). Thirdly, he found takers in all parties. Though he started with the help of the Congress, he served in the ministry of both Mulayam Singh Yadav of Samajwadi Party and Kalyan Singh of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and eventually also becoming part of Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP).

Tiwari, of course, was not alone to make a smooth transition from one vocation to the other. The spirit of the freedom struggle continued in the initial years of independent India, but as the Nehru era ended – and especially as the Indira era consolidated itself, politics was turning away from Gandhi and towards Machiavelli. In their race for power, few parties could bother about how the votes were won, and that is where criminals, particularly those involved in organised crime and the underworld, found their calling. They were setting up shop not only in UP and the adjacent Bihar but also in most regions of the country. Political parties also walked up to them to meet them halfway.

Over the years, the traditional characterisation of the underworld has radically mutated. Crime is not what it used to be. And conventional mafias are practically extinct; they have transformed themselves into suave, soft-spoken intermediaries between the industries and corrupt regimes across the world. They trot the globe, wield enormous clout and quite often subjugate state institutions to do their bidding. This is quite evident in the manner in which the state agencies like the police, CBI, Enforcement Directorate and Income Tax are amenable to be used as instrument for extortion and blackmail across the country. Quite clearly the difference between the state and the underworld has become indistinguishable. It would not be wrong to say that over the decades, the Indian state has been imitating its intimate enemy – the underworld – and has become much like it.

In Russia, they have a term for them, the vory. The rise of the vory is a classic case of transition and integration of the underworld into the country’s mainstream polity. Mark Galeotti, a Prague-based research scholar, has given a graphic account of internalisation of the Russian vory into the political mainstream in his book The Vory: Russia’s Super Mafia (Yale University Press, released in May 2018).

The book traces the genesis and evolution of the Russian vory since the eighteenth century, carefully scrutinizing its unique code and language, its strategies for survival and growth. Russia has witnessed tumultuous times – the Bolshevik revolution, Stalinism, the Cold War, the Afghan war, disintegration of the Soviet Union, and ultimately a turn to capitalism. Amid all these uncertainties, the vory have flourished and prospered at every stage. With Vladimir Putin, their evolution has gone a step further.

Galeotti’s conclusion is that in Putin’s time, the vory have become an adjunct of the state. They have been as thriving as they were at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution a century ago. Nothing describes it as aptly as a remark by Pavel Stuchka, a Bolshevik jurist in 1927, ten years after the revolution, who said, “Communism means not the victory of socialist law, but the victory of socialism over law.” From Lenin and Stalin to Gorbachev, the vory dominated either in the garb of ideology or pragmatism in a naked pursuit of power and wealth.

In Stalin’s time, the vory gradually acquired the language and idioms prevalent in Bolshevik revolution and carried on their criminality under cloak of socialism. Even Lenin found it strategically convenient to let a bunch of criminals infiltrate the communist ranks. Russia would have been different had Lenin shot more criminals than integrating them into the revolution.

However, the metamorphosis of the Russian mafia into a criminal-corporate entity found its bearing when Gorbachev launched Perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (opening up). In Putin’s time, the boundary between the organs of the state and the vory has become all the more blurred, and the latter are believed to have expanded their footprint across the globe.

Can we find an Indian equivalent of the Russian vory? India had its parallel to the vory in the thuggery. Like the vory, the thugs were bound by a code of conduct which was quite rigorous and backed by religious rituals. They were also blessed by the royals. In the Central Province, the ruling Scindia family was believed to be their protectors. Thugs were proud to carry on their profession of deceiving and waylaying innocent travellers and killing them in cold blood.

In a spine-chilling account of the thugs’ escapades, “Confession of a Thug” by Philip Meadows Taylor (1839), chief protagonist Ameer Ali so eloquently describes his profession when he says, “Thugee, capable of exciting the mind so strongly, will not and cannot be annihilated! Look at the hundreds, I might say thousands, who have suffered for this profession: does the number of your prisoners decrease? No! On the contrary they increase: and from every thug who accepts the alternative of perpetual imprisonment to dying on gallows, you learn of others whom even I knew not of, and of Thugee being carried on in parts of the country where it is least suspected, and has never been discovered till lately.”

How prescient are these words of Ameer Ali! Except for the fact that Indian thugs, like Russian vory, have mutated into a completely new strain of evil that has found legitimacy in the political mainstream and become intrinsic to the statecraft. Much like the vory, the thugs have got so much integrated in power structures that they are no longer distinct from the organs of the state.

If you have any doubt, look at the manner in which the country’s premier institution to combat corruption, the CBI, is engrossed in an internecine gang war within. Perhaps never in the history of the CBI was the agency so divided vertically as it is now, with different officers owing allegiance to different camps. The obvious result of this division is that the corruption cases are probed from the prism of “your corrupt” versus “my corrupt”. The CBI has not reached this situation overnight. Successive governments have turned it into a handmaiden of the party in power to browbeat rivals. The trend continues.

If you have any doubt on their modus operandi, recall the blood-curdling incident of 2016, when senior bureaucrat BK Bansal, his wife, daughter and son committed suicide in east Delhi, following intimidating inquisition by a bunch of CBI officials on the charge of corruption. The family found the abuse and torture from the CBI officials too humiliating and too frightening to handle. The suicide note named five CBI officials, but it did not stir a soul in the administration. (Its internal investigation found nobody guilty.)

Photo: Arun Kumar

Photo: Arun Kumar

More recently, a businessman from Raipur in Chhattisgarh chose to commit suicide after he was named as an accused in a case of making a video CD showing a state minister in a compromising position. Such cases are only the tip of the iceberg as the malignancy is quite deep-rooted. A criminalised CBI is enormously capable of subverting the government’s agenda. And that rot seems to be spreading furiously fast.

Ironically enough, the comprehensive report on criminalisation of politics by the NN Vohra committee in 1993 quoted extensively from a study paper prepared by none other than the CBI, on links among criminals, bureaucrats and politicians in Maharashtra. The report specifically referred to the evolution of Iqbal Mirchi from a petty thief to a redoubtable gangster and complicity of the state in his promotion. The report categorically pointed out the nexus among criminals, bureaucrats and politicians as crucial in creating an ecosystem in which the modern mafia thrives. Unlike the past when thugs used violence to achieve their ends, the new variant of mafias in today’s India are quite conversant with polite and persuasive talking but are not averse to using violence when all other means fail. They thrive on grey areas of democratic space, between individual liberty and public good.

Describing the evolution of the vory in Russia, Galeotti describes this phenomenon quite aptly by saying, “In an age of market economics and pseudo-democratic politics, where power is largely disconnected from any real ideology beyond an inchoate blend of nationalisms, arguably it is rather that the Vory have been diversified, and perhaps even colonized the wider Russian elites. There are racketeers, drug traffickers, people smugglers and gun runners – but there is also a deepening connection with the world of politics and business.”

Does it not hold for India too? Though the first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, held public life as sacrosanct, the criminalisation of the state and politics began in the time of his daughter Indira Gandhi. Deception and use of violence became intrinsic to statecraft and led to imposition of the Emergency. The state turned into a mirror image of the underworld. It went well beyond the political class, and it was during this time that the various law-enforcement agencies replicated the tactics of organised crime. Not only the CBI, but tax authorities too came to emulate the gangsters as they went out on their raid operations that were often extortion rackets. Their ways and their language started resembling that of the mafia.

Those days of the licence raj and the inspector raj had created lucrative opportunities in smuggling contraband, and the underworld could not have exploited these opportunities single-handedly.

By then the generation of freedom-struggle leaders had given way to a new breed of leaders who were practising their politics in a new India. Thus, not only the Congress, but also diehard socialists had no qualms in justifying violence and taking dreaded criminals into their fold in their quest for power.

When Rajiv Gandhi took over as the prime minister in 1984, he was conscious of the growing influence of mafias on the polity. But sooner than later, he became integral part of the sophisticated power culture spawned by the mafias. His family’s proximity to the arms dealer and Bofors middleman, Ottavio Quattrocchi, exemplified the deep penetration of mafias into the Indian state. It would be wrong to think that in Rajiv Gandhi’s time, the state was weakened. Far from it, he was a powerful prime minister with unprecedented mandate in his favour.

In the 1990s, the state had become pretty strong. Here once again a similarity can be drawn by referring to Galeotti words in The Vory: “The gangs which prosper in modern Russia tend to do so by working with rather than against the state, and a new political generation has risen to power dependent for their futures on Kremlin’s patronage rather than local underworld contacts.”

When Chimanbhai Patel was the chief minister of Gujarat, Abdul Latif – the petty bootlegger who made it big as Dawood Ibrahim’s henchman and inspired the Bollywood flick Raees – carried more heft than any cabinet minister.

India’s new-age thugs have also sailed through every dramatic transformation the nation has underwent, and economic liberalisation was no exception. The licence quota raj might have ended; the mafia raj has not. Criminalisation of politics – as measured by the number of MPs and MLAs with police cases pending against them – has been on the rise, but the other organs of the state are very much following in the footsteps of the political leadership.

Consider the relentless and ongoing series of ‘encounters’ in Uttar Pradesh in which only petty criminals if not innocents are killed while each of the bahubali is safe and secure. If anything can be more brazen than that, it can only be the chief minister proudly owning it up. His language is reminiscent of the mafiaspeak (“thok denge”) – derived, no doubt, from the lingo of the Gorakhpur underworld.

The prime minister’s call for an all-out war on black money has enthused a large section of officers, in CBI, ED, CBDT and other agencies, to launch offensive against the business class – for their own ulterior purposes. The banking irregularities have provided them with yet another cover to carry on their coercive tactics.

Granted that the modern state has violence built in its very nature, with a stated monopoly on violence (only the state can legally use force or even kill, the rest cannot). But crime is a different matter. What has happened in Russia, according to Galeotti, and what seems to be happening in India, is that the state, not knowing the limits of the use of force, has courted the underworld, and the line dividing the two has disappeared.

Ironically, this is the very opposite of what the Father of the Nation had dreamt. But he was a realist too. Writing in ‘Young India’ in 1925, just before the oft-quoted ‘Seven Social Sins’, Gandhi quotes ‘crisp sayings’ by one Dan Griffith:

“Modern society is in itself a crime factory. The militarist is a relative of a murderer and the burglar is the compliment of the stock jobber.”

ajay@governancenow.com