9.44 The irresistible force of even as powerful an idea as UBI will run into the immovable object of a resistant, pesky reality. So, what is the way forward, always remembering that the yardstick for assessment is not whether UBI can be perfect or faultless but only whether it can improve substantially upon the status quo?

Poverty reduction and illustrative fiscal cost calculations

9.45 What would a UBI potentially cost? This is not an easy calculation because it depends on a number of objectives and assumptions. This is described carefully in the following manner.

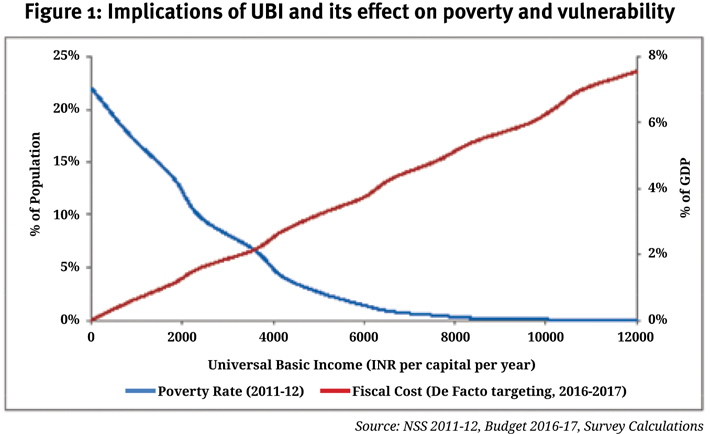

9.46 Based on the 2011-12 distribution of poverty it seems clear that going from a certain very low level of poverty to eliminating it will be prohibitively high. So, a target poverty level of 0.45 percent is chosen. Then the 2011-12 consumption level is computed for the person who is at that threshold. The next calculation is the income needed to take her above INR 893 per month, which is the poverty line in 2011-12. This comes to INR 5400 per year. Subsequently, that number is scaled up for inflation between 2011-12 and 2016-17: this yields INR 7620 per year. This is the UBI for 2016-17. For reasons explained later, the survey assumes that in practice any program cannot strive for strict universality, so a target quasi-universality rate of 75 percent is set. The economy-wide cost is then the UBI number multiplied by 75 percent. This yields a figure of 4.9 percent of GDP.

9.47 One important point to note. This UBI calculation does not require any assumption about the poverty headcount rate. It only requires consumption data on the marginal poor (the person at the 0.45 percent threshold) and the poverty line. Figure 1 shows UBI for various target poverty levels and corresponding fiscal costs.

9.48 The calculation assumes that private consumption has not changed at all implying that real income of the poor at the threshold poverty level of 0.45 percent in 2016-17 has not increased in real terms since 2011-12.This is unlikely to be true. Thus, the actual cost of a UBI to the government could be lower. If, for example, the real income of that marginal poor grew at the same rate as overall GDP per capita (which would be about 2 percent per year), the UBI amount will decline to INR 6540 per capita per year, costing 4.2 percent of GDP.

9.49 Since these calculations are based on 2011-12 consumption data projected forward, the implicit assumption is that UBI will be additional to the poor’s existing consumption which includes consumption from public programs (PDS, MNREGA, etc.). Is this reasonable or plausible?

9.50 On the one hand, a case could be made that if current programs are prone to exclusion error, which is likely to affect the poorest amongst the poor to a greater extent, then this methodology is not unreasonable.

9.51 However, there will be cases where PDS or fertilizer subsidies do reach most beneficiaries which will then have be taken into account if a measure of UBI as a replacement program is to be calculated. This is a complicated task because there will be a number of general equilibrium effects which will need to be considered. For example, replacing the PDS will increase market prices of cereals the poor face. Similarly, phasing down MGNREGS might reduce market wages for rural casual labour. Calculating these effects and hence the exact magnitude of subsidies will help refine any costing of the UBI.

9.52 However, as discussed earlier the UBI is likely to be more effective than existing programs in reducing misallocation, leakage and exclusion errors. In that case, the prior would be that not accounting for replacement would still not seriously affect the costing of UBI. After all, replacing one rupee of the fertilizer subsidy should require a compensating UBI of less than one rupee.

9.53 The process of determining a UBI amount is not a one-time exercise: as the UBI is a cash transfer, its ‘real’ value tends to be determined by inflation in the economy. Over time, the same amount of cash transfer may not buy the same amount of goods. It is, therefore, important to index it to prices such that the amount gets revised periodically. Politics can play a huge role in determining the exact amount each time it is up for revision and so it is important to set up a sufficiently politically neutral mechanism to do so. Ray (2016) proposes setting UBI as a constant share of the GDP to overcome this complication.

Where is the fiscal space to finance universal basic income?

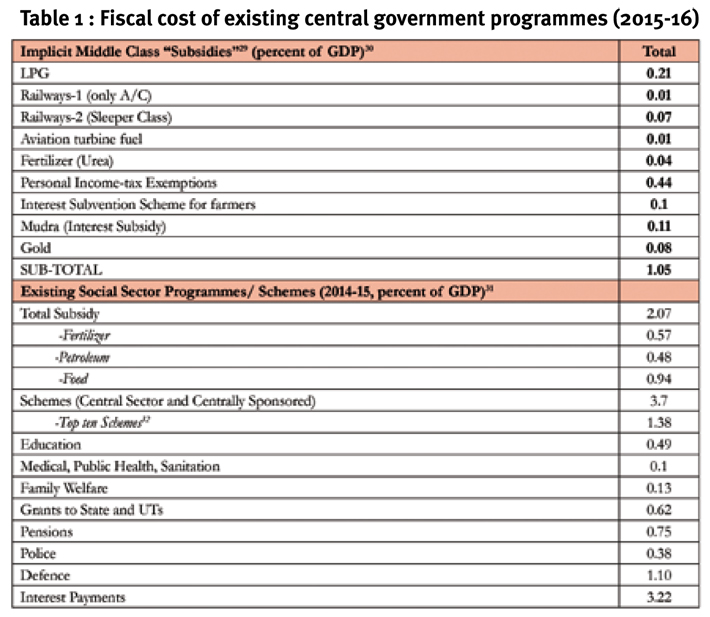

9.54 Table 1 presents the costs to the centre of running various welfare programmes and provision of services. Any government will have to decide on what programmes/expenditures to prioritize in order to finance a UBI. The lowest rungs of the table are presented for completeness, and it may not be advisable to replace these. In other words, while a UBI may certainly be the shortest path to eliminating poverty, it should not become the Trojan horse that usurps the fiscal space for a well-functioning state.

9.55 The first few rows of Table 1 are the subsidies for the non-poor/middle class households, equivalent to about 1 percent of GDP. Next listed are the government subsidies that account for 2.07 of the GDP (2014-15 actual). The corresponding figure for the states in 2011-12 is 6.9 percent. Among these,as table 1 shows, the subsidies for fertilizer, petroleum and food constitute the largest amounts. Previously, the chapter argues that the government runs a plethora of schemes– the top ten centrally sponsored or central sector schemes (not including subsidies) cost the state about 1.4 percent of GDP (2014-15 actuals). The remaining 940-odd sub-schemes account for 2.3 per cent of the GDP. Further below in the table, we list the other government expenditure: spending on education, health, pensions, police, defence and interest payments.

9.56 Here, it is clear that the magnitude of middle-class subsidies would be roughly equal to the cost of a UBI of INR 3240 per capita per year provided to all females. This will cost a little over 1 percent of the GDP – or, a little more than the cost of all the middle-class subsidies. However, taking away subsidies to the middle-class is politically difficult for any government. It is clear that while the fiscal space exists to start a de facto UBI, political and administrative considerations make it difficult to do this without a clearer understanding of its larger economy-wide implications.

Guiding principles for setting up universal basic income

9.57 Conceptually, a well-functioning UBI can be designed. How should one go about attempting to implement the same in a country as vast and complex as India? There exist, when translating the idea into reality, tensions that tug in opposing directions: there is the pull of universality, the need to contain fiscal costs, the difficulty of exit from existing programmes and the need to introduce a system that is not beyond the admittedly constrained ability of the Indian state to implement things at scale.

9.58 Below are three principles that could help guide thinking in this direction.

Guiding Principles for Setting up a UBI

9.59 If universality has powerful appeal, it will also elicit powerful resistance. The popular reaction to demonetization reveals a deep sense that the well-off gain from and game the current system to their advantage. In that light and keeping in mind fiscal costs, the notion of transferring even some money to the well-off may be difficult.

9.60 It is, therefore, important to consider ideas that could exclude the obviously rich, i.e., approaching targeting from an exclusion of the non-deserving perspective than the current inclusion of the deserving perspective. And there are a number of possibilities here.

Gradualism

9.61 A guiding principle is gradualism: the UBI must be embraced in a deliberate, phased manner. A key advantage of phasing would be that it allows reform to occur incrementally – weighing the costs and benefits at every step. Yet, even gradualism.

Choice to persuade and to establish the principle of replacement, not additionality

9.62 Rather than provide a UBI in addition to current schemes, it may be useful to start off by offering UBI as a choice to beneficiaries of existing programs. In other words, beneficiaries are allowed to choose the UBI in place of existing entitlements. This strategy has many advantages, beyond simply containing costs. It gives people agency, not only in that they have greater choice, but importantly because they have greater power in negotiating with the administrators who are currently supposed to be giving them benefits. This threat, expressed or latent, will then provide incentives to the administrators of existing programs to improve their performance. In the case of a fertilizer outlet, for example, the dealer knows that if he diverts the rice for his own purposes, he faces the threat of exit – beneficiaries will switch to a UBI. This, in turn, will reduce the quota of fertilizers allocated to his outlet.

9.63 Designed in this way, UBI could consequently not only improve living standards; it could also improve administration (and cut the leakage costs) of existing programs.

9.64 However, there are at least two concerns with the process listed above: one, by allowing the UBI as a choice over current entitlements, it reinforces all the current problems with targeting. This also ensures continuity of the misallocation problem with richer districts having a greater access to welfare benefits; furthermore, those excluded from the system will be unable to give anything up to avail themselves of the UBI; those well-off who are currently (wrongly) included will continue to have the right to be included.

9.65 Another problem is that this would be administratively cumber some. Although arguably a one-time event, who, for instance, in the case of fertilizer subsidies identifies and compiles the lists of persons who have given up access? This would likely be another opportunity for corrupt actors.

UBI for women

9.66 A UBI for women can, therefore, not only reduce the fiscal cost of providing a UBI (to about half) but have large multiplier effects on the household. Giving money to women also improves the bargaining power of women within households and reduces concerns of money being splurged on conspicuous goods. The UBI could also factor in children in a household to provide a higher amount to women. This addition, though, has three potential problems – one, it may not be easy to identify the number of children in a household; two, it may encourage households to have a greater number of children; and three, phasing out boys from beneficiary list once they reach a certain age (say 18 years) may not be easy to monitor and undertake.

Excerpted from the Economic Survey, 2016-17.