The Fourth Industrial Revolution has steadily amalgamated information communication technology (ICT) in every aspect of modern human life, having a profound impact on economic and social systems by altering business structures and consumer habits. About two decades back, ICT infrastructure was an augmented resource for business, but today with technical advances it has become the first layer of foundation over which other layers fortify the strength of an organization, to equip the business with capabilities to compete and contribute in a digital age. The United Nations also well recognizes ICT as a critical driver of the Sustainable Development Goals and an enabler of progress on the Millennium Development Goals.

Among the ICTs, the Internet is the most powerful, combining facets of hardware and software together to build a network of networks. As per a study conducted by World Bank in 2009, a 10% increase in broadband penetration leads to 1.21% per capita GDP growth in developed countries and 1.38% in a developing country. A report by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), published in 2016, estimated that a 10% increase in India’s Internet subscribers results in an increase of 2.4% in the growth of Indian state per capita GDP.

India, the world’s largest democracy, is very much a part of the cutting-edge digital revolution with the second highest number of internet users and mobile subscribers in the world in absolute terms. However, a comparative look at the ITU database shows that India is lagging in its ICT adoption in relative terms when compared with both developed and developing nations. Nonetheless, India is fast catching up. The Indian government with massive programmes such as Digital India, Smart cities, and BharatNet and a proactive policy regulation is ensuring that India does not miss the advantages and prospects offered by the digital revolution. The initiation of emerging technologies such as 5G, artificial intelligence, machine to machine communications and internet of things (IoT) shall further advance India’s digital trajectory.

On the policy front, all telecom policies (National Telecom Policy – NTP, 1994, NTP 1999, Broadband Policy 2004, NTP 2012) have propelled the growth of the ICT sector in the country over the previous two decades. The Telecom Commission’s (TC) heads-up to the National Digital Communications Policy (NDCP) 2018 is the recent development to thrust India’s digital empowerment. The telecom sector industry body, Cellular Operator Authority of India, seems to be satisfied with the latest policy. The industry’s concerns of the sector being under financial distress have been addressed with the rationalization of various taxes and levies, such as licence fees, spectrum usage charges, revenue sharing, universal service obligation fund, GST, etc.

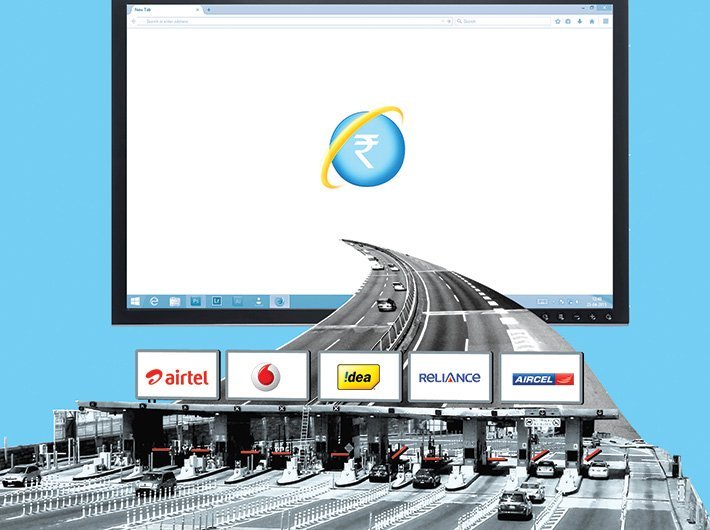

Most recently the TC gave its verdict on a much-debated issue around the world, net neutrality. The commission gave a heads-up to the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) recommendations on net neutrality put up in November 2017, which are backed by the doctrines of a free, open and non-discriminatory Internet. These recommendations forbid practices such as differential pricing, blocking, throttling, degrading, slowing down or giving preferential speed or treatment to any online content. However, TRAI recommends for fast lanes for specified services charted by the Departmentof Telecommunications (DoT) and allows operators to follow traffic management practices towarrant service quality. Also, the content delivery networks (CDN) and certain serious IoT services identified by DoT have been kept outside the ambit of net neutrality. Limited IoT services, which DoT exempts from the principle of net neutrality, include services such as autonomous transport systems that are heavily dependent on seamless connectivity and healthcare systems (for instance, if a remote diagnostic surgery is under progress). Internet traffic needs to be prioritized as even a millisecond of connectivity drop is critical.

The idea of open Internet has always been upheld in India. In December 2014, when Airtel announced to charge separately for Internet-based calls, the net neutrality debate was initiated across the country. The telecom major Airtel faced a strong backlash from Internet freedom activists and soon withdrew its plans. Subsequently, in April 2015 when the telecom giant proposed ‘AirtelZero’, an open marketing platform which let the users to access specified mobile applications for free while the data charges were proposed to be paid by the application providers. The plan was perceived as unjust and unfair and against net neutrality. A major argument was that smaller firms would not beable to pay for the operator’s data fee, which, will lead to unhealthy anti-competitive collusion between large companies and operators. At the beginning of 2016 Facebook’s ‘Free Basics’, which proposed to offer free Internet access in India for restricted content curated by the company, was also slammed.

Next, in February 2016, TRAI came up with the regulation, “Prohibition of Discriminatory Tariffs for Data Services”, thus prohibiting service providers from charging discriminatory tariffs based on thecontent/applications accessed by the users. The recent approval of the TRAI’s net neutrality recommendations has reinforced the idea that open and non-discriminatory Internet is much in favour of consumers and overall interest of the general public, thus, constitutes a solid base for Digital India.

Interestingly, India’s TC approval to net neutrality recommendations coincides with the US’s Federal Communications Commission (FCC) announcing the revoking of the Open Internet Order passed in 2015, and substituting it with the new Restoring Internet Freedom Order. Thus, the FCC consents Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to explore content discrimination and allow differential pricing models around it. The FCC’s principal concern, which motivated the repealing of the Open Internet Order, is that strict regulation would affect investments in the broadband space. Discriminatory pricing practices shall enable the service providers to earn more revenues and thus allow them to invest in broadband infrastructure and thus further facilitate Internet access in the nation.

Contrastingly, India’s regulatory authority believes that sufficient means are available to deliver Internet access to its citizens without compromise on the principles of net neutrality.

The NDCPm2018 envisages universal broadband access through initiatives such as BharatNet (providing 1Gbps connectivity to gram panchayats upgradeable to 10 Gbps), GramNet (connecting critical rural development institutions with 10 Mbps upgradeable to 100 Mbps), NagarNet (installing 10 lakh public Wi-Fi hotspots in urban areas) and JanWi-Fi (positioning 20 lakh Wi-Fi hotspots in rural areas). Meanwhile, the Telecom Commission also approved the deployment of over 10 lakh Wi-Fi hotspots in gram panchayats with viability gap funding of about Rs 6,000 crore by December 2018. Furthermore, a proposal to pilot fund projects (up to Rs 10 crore) through Universal Service Obligation Fund to provide connectivity through new alternative technologies, such as Li-Fi or light fidelity, has been cleared too. This funding shall be limited to companies, which are licensed under the DoT.

India envisages bridging the development service gap through ICT. The Internet is an authoritative medium to deliver service in healthcare, education and banking and a robust social equalizer. Unequal access to the digital world and discrimination of Internet content is likely to have repercussions for inequalities. The celebrated study by Avgerou and Madon, “Information Society and the Digital Divide Problem in Developing Countries” (2005), and a study by Wei, Teo, Chan, and Tan, “Conceptualizing and Testing a Social Cognitive Model of the Digital Divide” (2011) explains that socio-economic differences associated with digital disparities could intensify further if the existing gaps in ICT adoption are not bridged.

The absence of net neutrality in India could allow established deep-pocketed industry giants to enjoy disproportionate market power. If content and service providers could collaborate with ISPs and discriminate online content services, it would have been a significant market entry barrier for new and smaller companies in the internet service segment. This would be detrimental to new innovative digital platforms and to India’s vision of empowering citizens digitally. The TRAI recommendations are conducive for India’s start-up ecosystem and ensure a level-playing field in access, enabling new companies to reach out to the target audiences on the same terms as their incumbent peers.

While the TRAI’s recommendations are mostly upfront, there are a few controversial spaces. The regulator does not restrict the operators to engage in traffic management practices as long as they are justified and apparent. CDNs and specific IoT services also have been exempted from the net neutrality principle. CDNs enable an operator to deliver online content within its network without using the public Internet. This lowers the network congestion by freeing up space for non-exempted services to travel through the operator’s network.

As per TRAI’s recommendations, operators are forbidden from offering their customers the services of other companies like Flipkart and Facebook at subsidized rates, but the operators may buy content from companies like Amazon Prime, Netflix and host it on their network. Telcos such as Bharti Airtel and Reliance Jio offer their content concerning movies, music, etc., which is only provided on their networks, and are also permitted to practise price differentiation. Thus, even a stringent net neutrality policy draft leaves space for operators to manage limited content in a discriminatory manner. Further, Telcos concerns concerning over-the-top (OTT) service have not been addressed. OTT service providers use operators’ networks free of charge. OTT players like Google Duo, Skype, WhatsApp, and Viber offer free calls and messaging options, and operators earn nothing effectively when users use these apps. As the use of these OTT services increase, the revenue of the operators is likely to be adversely affected, while their networks gradually become dumb channels. While operators are liable to pay charges in the form of licence fees, spectrum charges, and follow the rules about the quality of service and network security, the OTT service providers are not subjected to such analogous regulations. However, as both of them practically offer identical services, telcos reason that OTT players should be regulated analogously. Defending their position, OTT players state that stringent regulation could affect and possibly choke innovation. Furthermore, consumers do subscribe and pay the fee for the data packs to access Internet services on the operator’s network, which offsets for the operator’s revenue loss.

Chavi Asrani is a PhD student of Economics at IIT, Delhi.

Palakh Jain is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Bennett University.

Tinu Jain is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at IMI, Kolkata.