The family group on WhatsApp went into a buzzing frenzy. Thumbs-ups, happy emojis, congratulatory messages. All in response to a message that made it seem as if the BBC was reporting on a survey conducted by...hold your breath...the CIA and the ISI, predicting a victory for the BJP in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. Only a few wondered why the spy agencies of the US and Pakistan would conduct a survey in India, and if they did, why they would make it public. The doubters were promptly silenced by invoking nationalism. No one checked the red herring BBC link that came with the message: it dead-ended at the BBC homepage; there was no BBC report, but no one bother

Clearly, this was fake news, being forwarded mindlessly by persons and groups to with whom it had resonance. This is the power of the social media that is shaping political narratives in 21st century Digital India. Its influence is bound to grow: since 2013, the number of internet users has grown 40 percent and data costs have fallen 95 percent. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that smartphone usage will double by 2023. Besides, over 300 million Indians use Facebook, and monthly, over 250 million access YouTube and over 200 million use WhatsApp. From rising to shut-eye, people remain glued to their phones.

Going beyond communication, social media has emerged as the biggest informal media organisation, disseminating political views and even parties’ agendas. If the BJP was seen as having won the 2014 election on the strength of its social media campaign, the 2019 election is being seen as a veritable social media election. All parties have set up “war rooms” disseminating their own versions of news, false or true, targeting specific demographics. And most of these IT cells are outside the purview of the Election Commission (EC) of India, since they are not officially connected to the parties.

Shivam Shankar Singh, a data analyst who quit the BJP last year, speaks of the levels to which parties may go: “A political party usually has a message they want to deliver for which they use social media advertising. The issue arises when the message they want to convey is communal or polarising in nature. This is also where fake news comes in. To shape the narrative that Muslims are evil, a party may resort to fake statistics on crimes by Muslims and videos from Syria and claim they are from Uttar Pradesh. To shape a narrative of nationalism, they will brand people anti-national and circulate content against them.”

What was the Cambridge Analytica scandal?

In early 2018, Cambridge Analytica, a political data analysis firm, harvested personal data of around 50 million people’s Facebook profiles without their consent and used it for political purposes. The firm worked on the 2016 Trump campaign. The 2016 campaign relied heavily on ad targeting, which may have used Cambridge Analytica’s Facebook data. Cambridge Analytica’s CEO Alexander Nix has been suspended since then. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has published a post outlining the company’s responsibility and has testified before the US Congress.

Consider the “chowkidar” slogan. The minute after prime minister Narendra Modi changed his official Twitter handle to “Chowkidar Narendra Modi”, all BJP leaders and BJP supporters added “chowkidar” to their handles. In return, the Congress started #ChowkidarChorHai on Twitter, which soon became a buzzword in election speeches and rallies. Such targeted campaigning has considerable power to influence elections and appeal to voters’ minds. A study by the Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), part of US-based think tank The Atlantic Council, revealed that automated Twitter bots were boosting hashtags both in support of and in opposition to Modi and manipulated Twitter trends in February 2019 ahead of the Lok Sabha 2019 elections.

A significant swing in results can also be achieved through the manipulation of electoral news feeds. “You receive it [hate speech] 10 times in a day through social media platforms. It becomes a shared reality. If you click on it, an algorithm queries it and recommends you another extreme video, which matches the interest,” says Apar Gupta, executive director, Internet Freedom Foundation. The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data scandal of 2018 is a case in point here (see box).

Though Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp are the major social media influencers, lesser known platforms like WeChat, Sharechat, and TikTok are also used widely by political parties. Singh says Facebook has a wider reach in rural India and Twitter is an urban phenomenon, both of which the parties use to shape opinions. In fact, more than voters, they seek to influence mediapersons. However, the best medium today, he says, is WhatsApp. “It allows for targeted messaging using demographic data where groups are created along caste lines. Fake news also spreads easily on WhatsApp with very little in the name of fact-checking, as the medium is encrypted. People belonging to a group won’t correct any fake news even if they know it’s false because it supports their pre-existing biases. This gives WhatsApp an edge for political messaging,” he says.

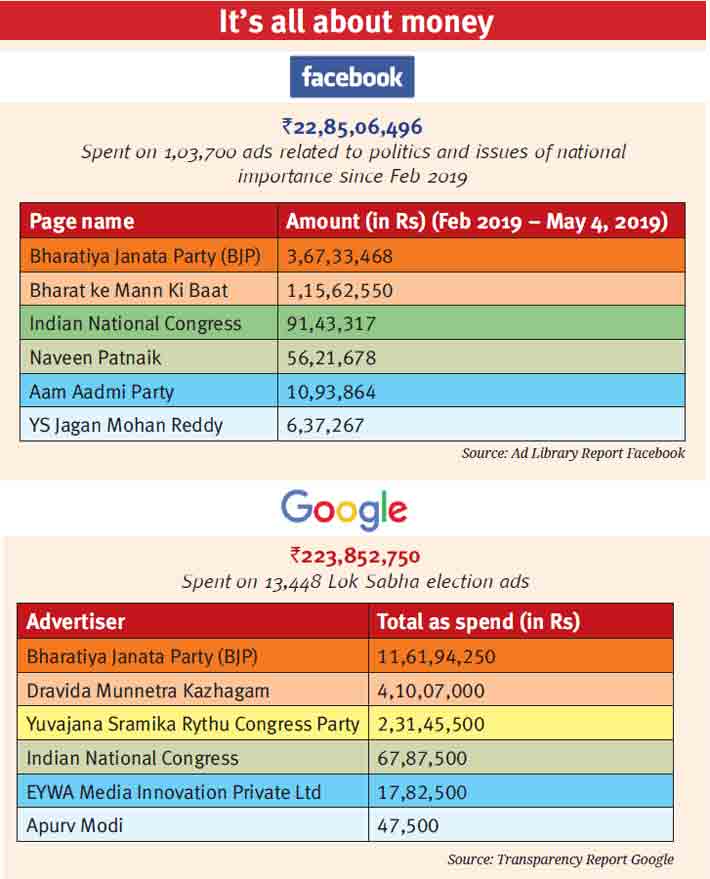

Cashing on this trend, political parties are spending huge amounts on social media campaigning with little check from the EC. As per the ad transparency reports of Google and Facebook, in February itself, Facebook had run over 51,000 political ads in India worth more than Rs 10 crore and Google declared 800 ads bought for Rs 3.6 crore. The BJP was the top spender on both platforms. Regional parties such as the YSR Congress and BJD were not far behind (see box).

Also, it is a misconception to think that the use of smartphones and therefore social media is restricted to urban areas only. “Even in rural India, with people who don’t own smartphones, social media has become a factor as the smartphone-wielding youth use the information they’ve received on WhatsApp in their daily conversations and present videos and graphics from WhatsApp as evidence of their claims,” says Singh. There are 250 million active internet users in rural India, and most of them access the internet on their mobile devices, reveals a report by market research agency Kantar IMRB. The figure is expected to reach 290 million by the end of 2019.

Therefore, in such a scenario, regulating social media is a necessity to ensure free and fair elections. The Model Code of Conduct (MCC) – the rules and regulations for conducting elections in India – does not mention anything on social media campaigning. It was only on March 20, when the EC issued some guidelines vis-a-vis social media, which are voluntary not mandatory (see box). This was in response to the efforts of a group of former civil servants and activists who had submitted recommendations to the commission, in 2018, to rein in digital platforms. The Commission had assured them it would consider their recommendations, but the group said in a press statement, “There has been little progress in the matter, except for the adoption of a virtually ineffectual Voluntary Code of Ethics mediated by the Internet & Mobile Association of India.”

At an event titled ‘Democracy, Elections and Digital Platforms’ on April 5, the group of civil society members, academics, former civil servants, ex constitutional office holders and retired CECs expressed their displeasure over the EC’s “too little, too late” code of ethics. Dubbing the EC’s step as “a token to the need of regulation”, the group urged the commission to use its power and do something tangible. It’s a tough call, for how can the election commission ensure fair play in cyberspace? But there are some do-ables.

Online spending

First and foremost, the EC can monitor online spending by parties during election campaigns – not just the spending by individual candidates. While Lok Sabha candidates are supposed to limit their spending to Rs 50 lakh-70 lakh (depending on the state they are contesting from), there’s no limit on expenditure by parties. Some reports say parties are likely to end up spending up to Rs 500 crore on online advertisement in the 2019 elections, doubling from the last election. “The entire model of online media is premised on the amount of resources you can put into it, which is a reflection of money power. So the person who has more people or money to pay for posts to trend or pay for posts to be within the ad network gets an upper hand,” says Gupta.

In order to bring a degree of transparency to digital platforms, Facebook and Google have since early this year been revealing the details of ad publishers and how much they have spent. These “Ad Transparency” reports reveal how parties have been spending heavily. But the complete picture doesn’t emerge: for in many cases, ad payments are made with cash, which is obviously not accountable. The EC should create a system for verifying and certifying such ads, and a beginning could be made by defining what constitutes a political ad. But in the free-for-all that is social media, doing this can be very difficult. For example, if a random person creates a joke meme targeting one political figure which by implication pushes for another party, would that count as a joke or an ad? Or, if a cartoonist puts out a work that favours one party one day and, at another time, puts out one favouring another party, does it amount to advertisement? The lines are blurred.

Perhaps the area in which the EC can take action is in making it mandatory for all parties and candidates to declare (a) their official websites, handles, etc. on all social media platforms; (b) whom they are paying for plugging their line; (c) consultants they have hired for digital influencing, and (d) making all payments traceable. Ways will be found around this, of course. As Singh puts it, “The BJP uses a lot of proxy pages posting pro-BJP content, but not officially the party’s. Data analytics costs [which the party is to show in accounts to the EC] are small compared to the money spent on nurturing such unofficial pages.”

As Facebook’s ad transparency reports show, unofficial pages and dummy accounts are doing all the dirty work. The two top spenders on Facebook, for instance, are ‘Bharat Ke Mann ki Baat’ and ‘My First Vote for Modi’, which have spent over Rs 2 crore from February 2019 to April 27, 2019. But the larger question is that when we don’t have full transparency in the funding of parties, how can full accountability in spending be achieved? Politicians have stuck together in parliament to allow anonymous electoral bonds (the supreme court has said these details must be shared with the EC, but in a sealed cover, so they won’t be open to public scrutiny) and funding through Indian subsidiaries of foreign companies. “The EC needs to assert its authority. In conditions that exist, parties can get secret funds and spend them through proxies,” says Gupta.

Laws and policies

For this election, the EC has woken up late to the reality of regulating social media. So why wasn’t it alert to the technological changes and think of updating the model code of conduct with changing times?

“The IT Act is completely silent on social media. The intermediary liability has also not been properly explored in the context of social media. Complicating that scenario is the fact that social media companies do not have offices in India. Therefore, mandating them to follow the mandate of Indian law itself becomes a challenge,” says Pavan Duggal, a cyber law expert.

Also, the regulations, which may appear too meek, are not binding. They were released after a few technology providers approached the EC. There was no initiative from the EC’s side. “The EC did not even hold one public consultation or release one approach paper despite fair warning after Cambridge Analytica happened. The EC had a closed door meeting with online social media platforms. They didn’t call political parties,” says Gupta.

One may argue that though regulations may appear too little, yet they are still there. But the fate of these regulations like most of policies in our country is dismal until they are enforced strictly. The role of law in preventing people is minimal. “If you are able to get an effective deterrence, the legal frameworks can be more successful,” says Duggal. Therefore, the EC can come up with “prosecutorial guidelines” which can help in enforcement of such policies, suggests Gupta.

The whole question actually rests on the EC. If the EC wants to regulate social media it should forcefully implement current regulations and take actions against those who violate the MCC. There have been so many instances of hate speeches this election, yet apart from Mayawati and Yogi Adityanath the EC did not penalise any other politician.

Curbing fake news

Social media is the new favourite medium of political parties to spread fake news, which can be used to target communities on the lines of caste, religion, ethnicity and linguistic identity. Hate speeches and fake news are politically beneficial, says Gupta. Political parties are banking on technology to promote either their own achievements – some of which might not be true – or malign other parties by circulating a particular information which is not true. In both the cases it is the false news which is being propagated.

Also, it’s never one piece of news that convinces people to switch sides, explains Singh. “It was sustained videos, graphics, media bytes and messages that together led to the success of the terms ‘anti-national’ and ‘urban Naxal’,” he says.

Social media has also played a major part in developing distrust amongst communities. “Once BJP claims that it’s the only party fighting evils while the

others are supportive of these anti-national elements, it leads to a swing in votes. The currently circulating fake news stories on how much money is being caught at Congress leaders’ houses in income tax raids is also shaping a narrative on how corrupt the Congress is,” adds Singh.

Promoting this flood of content are people like you and me. The social media phenomenon in India is very new and everyone wants to be part of it. “The only way by which they [people] know how to engage with technology is by forwarding what they receive. Today everybody has WhatsApp. The only way they engage with WhatsApp is by sharing everything. This creates a huge problem,” says Ravi Guria, deputy programme manager, Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF). “People don’t actually see the broader picture and for them it’s always one innocuous forward. But every forward makes for the information to go viral and that causes disturbance in the society,” he adds.

Therefore, curbing fake news becomes a huge challenge as it is difficult to pin responsibility on one person. “None of the political parties want to work in this direction because they themselves have understood the power of fake news and the impact of social media,” says Duggal.

As a result, we as people need to behave responsibly while dealing with technology and the EC too needs to pull up its socks. The EC should set up the strictest level of deterrence by initiating action whenever political parties and candidates indulge in fake news and hate speeches.

Duggal suggests that India can even learn from the experience of Malaysia, which enacted a dedicated law on fake news last year. “Unfortunately, India does not have a legal framework for regulating fake news. In fact the term ‘fake news’ is not defined by the law. In India people also believe that they have unbridled freedom of speech and expression on social media,” he says. Therefore, the country can come up with a legal framework that is in sync with the basic structure of the constitution and not adopt just a copy-paste approach.

Role of tech providers

So does the whole power rest on the EC and the masses alone to stop exploiting social media, or are the technology providers also responsible in some way? After all, the dubious content is shared on their platform. After much hue and cry from India and abroad, technology providers have taken some steps to curb fake news to safeguard democracy. In April, Facebook took down 687 pages and accounts linked to individuals associated with the IT Cell of the Congress, and 15 pages and accounts linked to an Ahmedabad-based IT firm, Silver Touch, for “inauthentic behavior”. Silver Touch is behind PM Modi’s NaMo App. WhatsApp, on the other hand, has restricted the number of forwards to only five.

Twitter too has taken a slew of initiatives to fight false and propaganda news. “We are continuing transparent and consistent communication with political parties from across the spectrum, as well as the Election Commission of India, so that they know how to report suspicious, abusive, and rule-violating activity to Twitter,” says a Twitter spokesperson. Twitter has developed machine learning tools to identify and take action on networks of spammy or automated accounts. This helps it in tackling attempts to manipulate conversations at scale, across languages and time zones, without relying on reactive reports.

Major technology providers like Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp have even partnered with a lot of NGOs and media outlets to spread awareness about fake news and how to use the technology in a responsible way. “We continue to hold training sessions and workshops with both regional and national parties (BJP, INC, CPI, CPI-M), and their respective state units... At the request of the various political parties, we held 15 training sessions on #ElectionsOnTwitter with different political parties, reaching hundreds of candidates, elected officials, and relevant party officials,” says the Twitter spokesperson.

WhatsApp has partnered with DEF and has conducted ‘Fighting Fake News’ workshops in 11 states across the country. “The most important finding in these workshops was that it is the older generation which is responsible for sharing misinformation as lack of awareness is more in them,” says DEF’s Guria, who is spearheading such workshops.

Therefore, he feels that it is the people who have to be aware and mature enough when they use technology. “They have to realise that they have a huge power in their hand, which is the mobile phone by which they can reach out to a larger section of people instantly,” adds Guria.

Explaining this further, Guria says, “We make the technology and technology doesn’t make us. If we stop using WhatsApp then it is harmless. For example, one can use a knife to cut either a nutritious vegetable or to stab someone. As much as we say that technology companies are responsible and I believe they need to take some responsibility but I think most responsibility lies on people who are using it.”

Facebook has partnered with third-party fact-checkers to verify the authenticity of the content posted on its platform. It has roped in platforms like Boom Live to check the veracity of content.

Voluntary code of ethics

- Facilitate transparency in paid political advertisements, including utilising pre-existing labels/ disclosure technology for such advertisements

- Verification of the identities and locations of all political advertisers

- Disclosure of candidates’ social media accounts and expenditure

- Norms aimed at curbing misinformation and hate speech by candidates include pre-certification of political ads by the ECI’s Media Certification and Monitoring Committee and the creation of dedicated grievance redressal channels through which the ECI can flag and takedown problematic content quickly (within 3 hour of violation)

- ECI to notify relevant platforms of potential violations of Section 126 of the Representation of People Act, 1951, and other applicable electoral laws. The section states that in the 48 hours leading up to the conclusion of polls in any constituency, election content shouldn’t be circulated on television and mediums — like the internet

As explained earlier, the social media giants have even released their ad transparency reports, detailing political campaigning ads and ad spent. So efforts have been made by the technology providers but users have outsmarted them. People have already come up with ways to bypass them. Also, these efforts seem very little in the face of the huge problem that we face. “Companies have already built systems to beat the WhatsApp forwards restriction. They’ll have to plug these loopholes. There’s also tremendous pressure on these tech companies from various quarters to prevent them from taking action but I hope their efforts persist,” says Singh.

But the task to rein in social media is extremely challenging and is being faced the world over. “The solution will come through technological innovation, not legislation. The platforms, to their credit, are trying to clamp down on fake news. Facebook shut down a lot of pages from both BJP and Congress that exhibited bot-like behaviour. The challenge is bigger on WhatsApp due to the platform’s encrypted nature but they are tackling new group creation – the problem here is that the BJP will have a competitive edge built into the system now as old groups haven’t been touched and BJP has a lot of them already since they started sooner,” says Singh.

But Gupta feels that putting the onus on technology providers is an easy option for the EC to wash its hands of. “When you can’t register an FIR on a clearly communal speech and at the same time you want the platforms to ban that speech to prevent proliferation – that is completely mixing up priorities in terms of the responses necessary to achieve prevention of hate speech,” he says.

Agrees Guria: “Everybody is trying to juggle with their own understanding of the role of technology. Tech companies have their own perspective, the government its own and users their own. Privacy and security are important but if you over-regulate technology then it beats the whole purpose.”

The road ahead

Terming social media as a “complex jigsaw puzzle which none of the stakeholders want to touch”, Duggal says that the legal framework for this has to be robust. The responsibility cannot be fixed on a single stakeholder and all need to take collective efforts to safeguard digital democracy.

He says that certain reasonable restrictions can be imposed on freedom of speech and expression as “right to freedom of speech and expression on social media does not mean an absolute right to defame another person”. Moreover, “appropriate political will is required, which is currently non-existing,” he adds.

Agrees Gupta, who also believes that it should be a “collective responsibility”, but the principal share of blame rests on political parties and the EC for not doing enough. “Indian elections are not only being jeopardised by fake news and propaganda, they are also being jeopardised completely by political parties,” he says.

ridhima@governancenow.com

(This article appears in the May 31, 2019 edition)