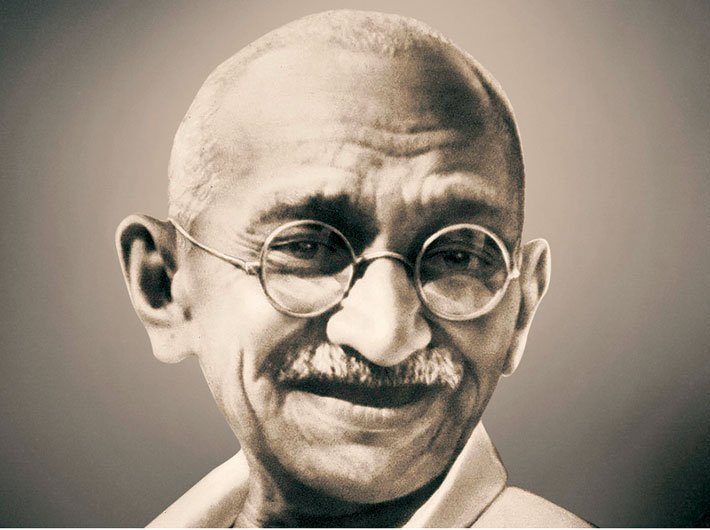

On Gandhi’s birth anniversary, reproducing excerpts from historian Amar Farooqui’s essay exploring the two sides of the Mahatma

On the occasion of the birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, renowned academic publishers Sage have opened access to many notable articles and essays on the Father of the Nation. Here we reproduce an excerpt from one of them, well-known historian Amar Farooqui’s highly original and detailed article investigating the links between Gandhi’s spiritual quest and his politics.

The formal citation of this article is thus:

Farooqui, A. (2020). Gandhi’s Spiritual Politics: Austerity, Fasting and Secularism. Studies in History, 36(2), 178–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0257643020953564

Here is the beginning of the article:

An Austere Beginning

It is rather astonishing that very early on in his life, in his late teens and early twenties, during his fairly short stay of a little less than three years in London, Gandhi should have managed to get acquainted with such large number of people, people from very varied backgrounds with extremely diverse interests and ideas, unlike run-of-the-mill students in England. Surely this experience had something to do with his temperament, his ability to have a conversation with anyone whose views interested him irrespective of whether he agreed with them or not. The ‘argumentative Indian’ in him was irrepressible even in his early youth, his shyness notwithstanding.

A robust interest in ideas about dietary discipline, rather than a narrow obsessive concern with abstaining from the consumption of flesh, as has at times been assumed, took him to unusual eating places in London. On his voyage to England, he had already discovered aboard the ship that it was possible to have wholesome vegetarian food if one was not too finicky. He tells us that he requested

“the chief steward to supply some vegetable foods and I had usually for breakfast oatmeal porridge, milk and stewed fruit and bread, butter and jam and marmalade and cocoa. For dinner I had rice, vegetable curry, milk and jam pastry, stewed fruit, bread and butter. For supper, bread, butter, jam, cocoa, some lettuce with pepper and salt and cheese.”

Within three weeks of his arrival in London, he had located a good vegetarian restaurant offering a wide range of dishes at reasonable rates. Besides, he had soon put in place arrangements for cooking some of his own meals in order to cut down on his expenses as well as to be able to have a more nutritious diet.

There were quite a few fashionable restaurants in London which catered to a clientele experimenting with forms of vegetarianism as part of an intellectual and spiritual quest. Some of the patrons propounded theosophical ideas, others sought to promote versions of vegetarianism, while yet others were connected with the Esoteric Christian Union. Gandhi’s engagement with vegetarianism and theosophy gave him access to overlapping intellectual circles comprising an assortment of characters with unorthodox ideas, lifestyles and fads. Charles DiSalvo perceptively observes,

“[i]t was in his study of theosophy and his embrace of the cause of vegetarianism that he discovered a way to bridge the distance between faithfulness to himself and things Indian, on the one hand, and, on the other, his attraction to the higher strata of British society where, at least at the edges, theosophy and vegetarianism were thriving.”

These were not necessarily people with the most progressive ideas, though they were often well meaning and had no intention of being nasty or disagreeable. Gandhi was at ease among them. He soon learnt to converse with these new friends, overwhelmingly English, on equal terms, which would have made him more self-confident. Thus, he exhibited no diffidence while accompanying a Gujarati writer, then residing in London, to call on the venerable Cardinal Manning, Catholic archbishop of Westminster. Although the meeting was very brief and formal, the cardinal’s personality left a deep impression on Gandhi who had just turned twenty. He was still somewhat in awe of him when he vividly recalled the meeting nearly thirty-seven years later, devoting several paragraphs to it in his autobiographical account. There is a passing reference in these passages to the great 1889 strike of dock workers, in which Cardinal Manning intervened on the side of labour and helped to bring about a settlement that was favourable to the dock workers. Surprisingly, Gandhi did not take much interest in the strike itself, surprising because this was a momentous struggle that was to transform the character of trade unionism in Britain. We can discern here a disinclination to be enthusiastic about left-wing ideas and radical mass mobilization. He was to remain steadfast in this attitude to the end of his life. The refusal to engage with socialist or Marxist thought marked the limits of his world view and goes a long way towards accounting for many of the contradictions in it. Gandhi seems to have been more attentive at that time to Manning’s simplicity and his reputation for frugality: ‘So far as food is concerned, his food did not cost Cardinal Manning more than nine shillings per week if what is written about him be true…. His strict abstinence from wines is notorious’. It was approvingly noted that ‘his ordinary meal, in public or private, is a biscuit or a bit of bread and a glass of water’.

Nineteenth-Century Saurashtra: The Curse of Colonialism

As we know, it was a respected family friend, Mavji Joshi, who had initially encouraged Mohandas to go to England with the objective of becoming a barrister. This was shortly after his father passed away in 1885. Mavji’s advice carried considerable weight especially since his own son, Kevalram, was a busy lawyer and had contacts in England. Mohandas’ elder brother, Lakshmidas, who was present during this consultation at Rajkot, concurred with the suggestion, though with a few misgivings. ‘The zeal with which Gandhi hurled himself into the project of going to London’, trying to mobilize funds, and obtaining the consent of family elders is revealing. He made a trip to Porbandar, the hometown of the Gandhi family, travelling on his own, both to seek the blessings of senior members of the family as well as to seek financial assistance. No aid was forthcoming. Besides, Gandhi had to put up with being snubbed by the principal British colonial official posted in Porbandar, his first face-to-face meeting with a European, when he approached him for support. The important point is that Gandhi continued to persevere. Twenty years later, he met the same official, Frederick Lely, at a formal get-together when he was in London in 1909 to gather political support for reversing recently introduced legislative measures in Transvaal aimed at further restricting the rights of Indians.

[The excerpt reproduced with the permission of the publishers.]

The article can be read in full here:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0257643020953564