The number of women addicted to drugs is on the rise. And yet, all across India, there are only three de-addiction centres for women

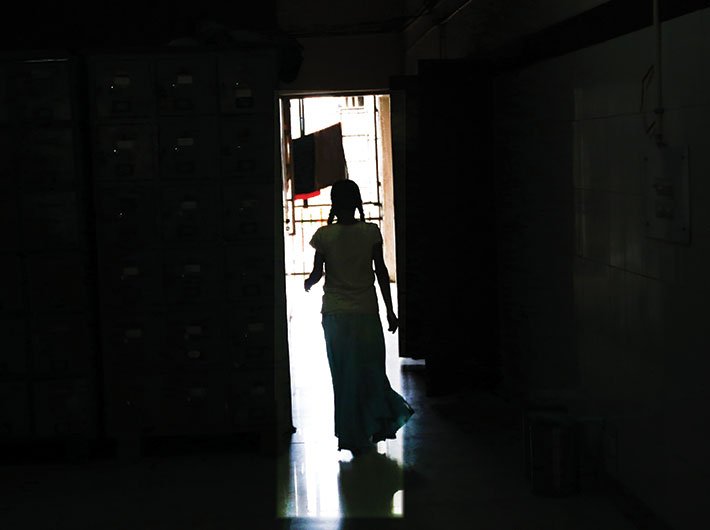

Meena, a solemn, raspy-voiced woman in a black salwar-kameez, is gyrating to a Bollywood number with gusto. The vivid range of her expressions counterpoints her lanky frame. Life is limping back to normal for Meena at what she calls her new home: Parda Bagh, the only de-addiction centre for women in Delhi, deep in the dingy lanes of Daryaganj. It’s a pale grey building. There’s a community hall on the ground floor and the first floor, divided into rooms and a kitchen, almost like a home, is where addicts like Meena endure the process of recovery.

“The numbers are going up...it’s very difficult to deal with women drug addicts,” says Vishakha, a caretaker at Parda Bagh. “It may seem to many that a girl is fragile and so would be consuming less substances than men. But it’s not so. Female addicts have their own history, and it’s very difficult for them to unburden themselves of their addiction by themselves.”

Though there is no way to arrive at exact numbers, psychiatrists and others in healthcare are in no doubt that the number of women abusing substances (from alcohol to all kinds of drugs) is increasing. According to a report of the National Institute of Social Defence (under the ministry of social justice), studies of patterns of substance abuse show the increasing use of substance among women and children. “I come across over 30 cases of drug addiction among women daily,” says Dr Atika N Sakhawat, a psychologist and researcher. “Earlier, we hardly ever saw any case of women drug addicts. The numbers have gradually increased over the years. More than 50 percent are under the age of 30.”

International organisations, too, have recognised the growing problem – and its dangers. As far back as 2005, the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs formally recognised the “adverse impact of drug use on women’s health, including the effects of foetal exposure” and urged member states to implement “broad-based prevention and treatment programmes for young girls and women” and to “consider giving priority to the provision of treatment for pregnant women who use illicit drugs”. It also asked the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to include more gender-disaggregated information in its drug reports. A 2012 Commission on Narcotic Drugs resolution noted that “women with substance abuse problems are often deprived of or limited in their access to effective treatment that takes into account their specific needs and circumstances”. It urged member states to “integrate essential female-specific services in the overall design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes addressing drug abuse and dependence”, including the integration of “childcare and parental education” in treatment services. What’s more, it zeroes in on the fact that women addicts are vulnerable to sexual abuse and violence and tells member states to take this into account in the policies they frame.

However, India has been slow to respond. For a country of more than 585 million females, India has only three de-addiction centres dedicated to women – one in Delhi, one in Manipur, and one in Mizoram. The condition of government-run de-addiction centres (where men and women are usually treated together) is pathetic; addicts who can afford it prefer private de-addiction centres, which are expensive, and those who cannot register and wait for their turn at centres run by NGOs. But state governments and the centre must act. For it is women from the worst-off sections of society, especially in cities, who are most vulnerable to drug-taking. Pushed by circumstances into an addiction, these women get trapped into an ineluctable cycle of exploitation, violence, and subservience to their exploiters. Women like Meena.

***

“The only time I would go back home was to wash and shampoo my hair, when my father was not at home,” says Meena, now in her early twenties, about her childhood. One of eight children, she grew up in Govindpuri, a poor resettlement colony in south Delhi. “My father would beat us if we stayed at home. Some four or five years ago, I decided to move out. My mother didn’t say a word, probably because she had seven other children to look after. Me and my friend Sudha, we would roam the streets and galis of Khanpur, Sangam Vihar, Tughlaqabad and beg or borrow. I was homeless and sometimes I’d not get food for five days. But I had no other choice.”

A friend introduced Meena to the company of some males, who introduced her to charas, ganja, smack – all kinds of street drugs. “Most of the time, though, I was on ganja,” she says. “I’d keep sleeping for days and wake up to busy streets around me. I could live without food, not without drugs. I couldn’t think beyond drugs. I have been raped, gang-raped many times when I was high,” she says in a level tone.

It became so bad that in order to sustain the habit, she’d frequently indulge in sex with strangers. “I’d say, ‘If I’ll get something for it, I’m ready.’ And then I would let them do anything,” she says. For more than six years she lived in a daze. In January this year, a team from Parda Bagh picked her up from Govindpuri and brought her to the centre.

“Her condition was pathetic when we brought her here,” says Vishakha. “She was unconscious for four days. She still cannot speak and hear properly. When she came here, she would burst into a rage and throw things at others. She wasn’t normal. Even now, her behaviour is unpredictable.”

***

Chanda, a quiet and pale teenager, has not been sleeping properly for the past few days. Like Meena, she was brought to Parda Bagh in January. Vishakha says not a day passes when she forgets to keep track of the number of days she will have to spend at the de-addiction centre. (Addicts are usually kept at the centre for four to six months.) “Two weeks more, and I’ll be free,” says Chanda with a sigh. “I feel homesick here.”

Chanda’s mother works at a tea stall, and as a child, her mother would take her to the workplace and that’s where she started doing drugs. She made some friends there, and one of them introduced her to some “new friends” who were smoking. “With my friend, I slowly got into smoking cigarettes, bidis, hash and ganja. First, I couldn’t take it, but soon I started enjoying it. For two years, I was completely into drugs. I would not go home. I would not eat at all, I could not see and feel beyond drugs,” she says, gasping. After that, she retires to her room.

But Vishakha offers a different way of looking at Chanda. “She’s just the opposite of what she seems,” she says. “She’s sharp, she’s crude, and has managed to run away from this centre thrice, once by breaking a grilled opening on the second floor, slipping out through it and probably shimmying down a pipe. All because of the company she moves in. They would rob people to pay for their habits.”

***

Speaking of the special care and treatment women addicts require, Dr Rajesh Kumar, executive director of SPYM, a well-known voluntary group devoted to de-addiction, says, “It’s a common perception that a woman would be consuming less quantities of substance (alcohol or drugs) than a man. But from case studies at SPYM-run de-addiction centres, we have found that women often consume more drugs. Most of the time, they are forced into drugs by boyfriends or husbands at home, or on the streets. Some are forced into sex, some into other kinds of torture. And there’s a vast difference between men and women undergoing de-addiction.”

He says the psychological profiles of male and female addicts are different; and the physiological impact of drugs on them is different too. This calls for different approaches to treating them. Dr Kumar mentions a 2014 case of a couple brought to SPYM for de-addiction. “The medicines and dosages which worked for the male did not work for the female. We couldn’t understand it. Later, we found out that, though the couple was doing drugs together, the female had been consuming far more drugs than the male,” says Kumar. “We had to give them extensive treatment and their de-addiction took much longer.”

Kumar stresses on the need for having more de-addiction centres exclusively meant for women, as the number of female addicts has been shooting up.

***

According to experts, day-to-day frustrations and the stress of modern urban life has contributed to the increase in the number of female addicts. However, exploitation and coercion or compulsion into drug use is also a major factor as far as female addicts are concerned. In the northeastern states, there has been a steady rise in alcoholism and drug abuse among women; death from overdosing or HIV/AIDS contracted from sharing needles is also on the rise.

While the northeast might have regional problems of its own, across India too, in rural areas as well as big cities, there is a rise in number of women addicted to alcohol or drugs.

“Many families are unwilling to accept that a woman member is addicted to drugs or alcohol because they don’t want society to know or judge their family, so we send peer educators to counsel them and make them understand the consequences of denial,” says Vishakha.

The very fact that there are only three de-addiction centres for women in India shows that the government is yet to wake up to the problem. Officials in the ministry of social justice say they do not have data about the number of women addicts. “There is hardly any such data,” says Kumar. “It hasn’t been formulated by any government agency till now. In fact, at SPYM, we are now encountering more and more cases of young women addicts, both from affluent and humble families. From the trends we have observed here, the indications are that women are taking to drugs in a big way.”

A caregiver who works in an NGO-run de-addiction centre speaks of the problems of having male and female addicts in the same facility. She says a government-run centre in Delhi is meant to accommodate 60 patients but is choked with more than 80. “Male and female addicts have to live together, sharing rooms, bathrooms, toilets. When an addict is brought to a centre, he or she is in no condition to interact with people, leave alone sharing rooms. In such a condition, male and female addicts are often forced to share space, which can be pretty uncomfortable. There are cases of addicts having sex, hooking up with other patients. Plus, it can be potentially dangerous for women addicts,” she says.

Given such conditions, it isn’t surprising that many women leave midway. Moreover, the nature of addiction being such as it is, many patients – male and female – suffer relapses. Lack of education among the poorer sections, and the social conditions they return to after treatment, too, create fertile conditions for them to return to the habit. Vishaka, in fact, is quite sure that some of her wards will return to the same company that pushed them into addiction.

“We cannot help it,” she says. “The rehabilitation policy is to be blamed. According to the policy, once the process of de-addiction is complete, it is the patient and her family who are the deciding authority as to where the addict would live. In most cases, the addict decides to live either in their dysfunctional families or go back to the streets.”

(The story appears in the July 1-15, 2017 issue of Governanance Now)