The theorist of the self and modernity is the great diagnostician of our everyday pathologies. The introduction to a new collection of essay by fellow thinkers charts the path his inquiry has taken over decades

Modernity, its Pathologies and Reenchantments

Modernity, its Pathologies and Reenchantments

Edited by Shail Mayaram

Orient BlackSwan, xx+396 pages, Rs 995

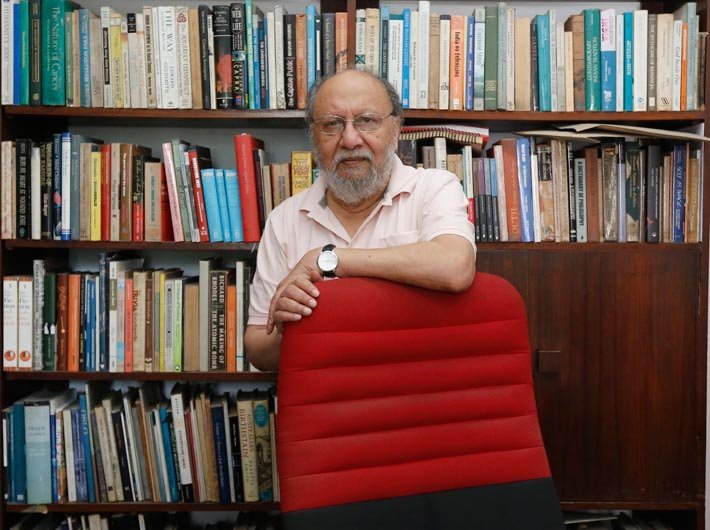

Ashis Nandy is for long known as India’s preeminent public intellectual. He is so, however, by virtue of his interventions from public platforms – short articles and interviews in mass media, speeches and lectures at public events like lit fests. His core theoretical work is something the larger leadership might not have accessed much. His numerous books – especially ‘The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self under Colonialism’ (1983) – might be perceived as academic works, meant for students, scholars and specialists.

That is unfortunate. Moreover, we do not have introductory works on the lines of ‘Ashis Nandy for Beginners’. Simplification has its own pitfalls and it is looked down upon for a variety of reasons. But Nandy’s thoughts on what colonialism has done to the Indian mind offer the most explanatory illuminating commentary on post-independence India, especially its politics.

Also read: An interview:

http://www.governancenow.com/news/regular-story/ashis-nandy-interview-i-am-afraid-we-are-in-trouble

A force that was once on the margins starts gaining traction, what was unthinkable till yesterday becomes commonplace today, what is unspeakable will become the norm tomorrow. Political analysts are flummoxed, how could it happen? With a clinical finesse, Nandy makes the diagnosis: the conflicts engendered by colonialism and modernity have bruised our collective sense of the self.

Terms like ‘fascism’ and ‘authoritarianism’ have often been thrown around in India, but it is only Nandy who would turn to the detailed parameters (devised in a long-term systematic study led by German thinker Theodore Adorno) and check how many of them apply to the Indian leadership. (The original essay, ‘Adorno in India’ was published in one of his earliest collections, ‘At the Edge of Psychology’, in 1980.) His essay on Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination remains one of the most engaging of the academic works on the Mahatma.

His output over the decades is spread over several books, and a beginner may find the variety of themes and range of sources bewildering. His colleague Shail Mayaram’s essay, ‘Walking with a Flâneur to Modernity: Reflections on Ashis Nandy as a Theorist’, which forms the introduction to this volume, could be the most helpful guide to the new reader.

She presents two parts in a nod to the tradition of Indian philosophical debates. The ‘purvapaksha’ undertakes “a journey through his major ideas expressed in some forty years of published work. These include his discussion of colonisaiton and de-colonisation, cosmopolitanism, knowledge systems and the relation to Freud, and above all, the question of gender.” The Uttarapaksha “consists of my interlocutory remarks relating to his discussion of the decolonised mind, anti-colonial nationalist thought and masculinity.”

The volume has several fellow travellers coming together with independent essays that assess Nandy’s work in a selected area or respond to it by charting out fresh trajectories. The aim, as the editor notes, is to “set the stage for a consideration of how we might take his work forward.” The contributors include Rajeev Bhargava and Partha Chatterjee among several thinkers from South Asia and elsewhere.

The book is divided into two sections: Pathologies of Modernity, and Reenchantments of Modernity – the two parts of Nandy's object of inquiry. In a celebration of the theorist extraordinary, the collected essays “address Nandy's view of categories such as civilisation, community and identity, as well as his critique of history and call for an alternative to history. The contributors deepen our understanding of the pathologies of modernity and reflect on spaces that have been resistant to modernity, and can therefore be potential sources of reenchanting our world.”