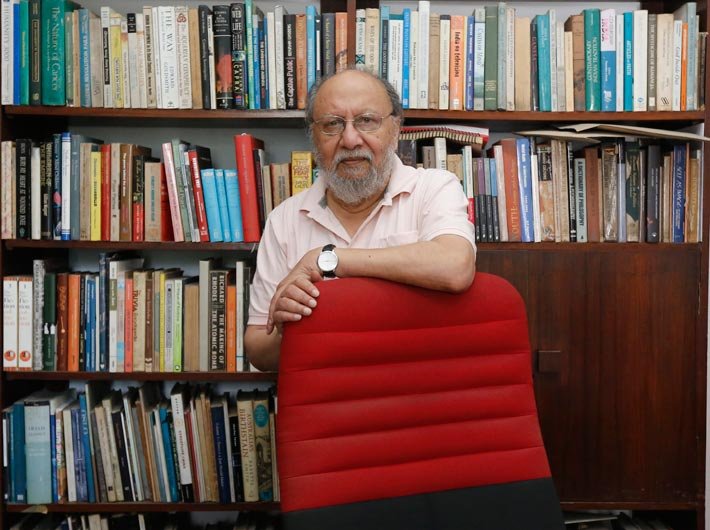

Ashis Nandy is arguably India’s most formidable public intellectual of his generation – and often the most controversial too, for his maverick and unusual insights. Originally trained as clinical psychologist, he has written at length on politics, culture, cricket and cinema, among other things. In an interview with Pankaj Srivastava, Nandy talks about the contemporary political concerns.

What is your diagnosis of India 2015?

I think it is a lively, colourful democracy, but it is also increasingly getting criminalised. Also, I agree with Lal Krishna Advani that there are emerging rather strong authoritarian streaks, not only within the ruling party, which has virtually become a one-man party, but among other parties too. I do not see any party that is open to competition within itself. They compete with other parties, not within themselves. There are no democratic structures within the parties. My diagnosis of Indian political culture at the moment is on the whole grim, in the sense that all societies that have gone through or sought a spectacular development have invariably gone through authoritarian phase unless they had colonies. I am afraid we are in for trouble. The attempt to tame NGOs, the media, and the judiciary are the first steps in that direction and the very fact that these attempts were made also under the previous regime and are being continued under this regime doesn’t speak well of the future of Indian democracy. If one thinks that just by removing Narendra Modi or the BJP one could remove the threat of authoritarianism in India, one is living in a fool’s paradise.

More than a decade before the 2002 Gujarat riots, you had met Narendra Modi. After that meeting, you had described him as a classical clinical case of fascism. Now he is the prime minister. What is your theorisation about him now?

Modi has been in politics for a long time and has learnt many things. He understands now that the political process will not bend to you, you have to bend to the political process. He has softened his stands in public, but his style of governance is still extremely centralised, dismissive towards other politicians, particularly those outside his party. And within his party, he depends more and more on bureaucrats and on politicians who act like bureaucrats. He likes appointed CEOs more than politicians.

The Modi government organised a mega event on the international yoga day. Thousands including bureaucrats and soldiers performed yoga along with the PM in Delhi. How do you react to that?

I thought yoga was a healthy diversion of politics and the virtual reality of visual media. I never thought it could be politicised or turned into a media spectacle or a contestant for a Guinness record. Indian politics is becoming increasingly media-centric. Modi is a product of that culture which depends heavily on spectacular politics, spectacular speeches and spectacular appearances. He thinks his visual presence is important. This is borrowed from the United States and is part of a presidential style of politics. This style has now entered all democratic systems to some extent. Now I am a great devotee of the leaders who are boring and colourless like PV Narasimha Rao, because they have to win elections on serious issues. They cannot win by their looks, by their clothes, by their monogrammed suites. Not even by their skin colour, oratory or glamorous girlfriends. They have to win their battles through their work and politics.

But don’t you think that the great Indian middle class is enjoying this politics of spectacle? Even intellectuals don’t address real issues like farmer suicides and rights violations.

But don’t you think that the great Indian middle class is enjoying this politics of spectacle? Even intellectuals don’t address real issues like farmer suicides and rights violations.

That is partly because the media constantly focuses on non-issues and politics has become more media-centric. There are staged daily quarrels on the channels and experts are expected to arbitrate between the parties. Intellectuals should have the courage to say that they will not say what they don’t want to say or what they don’t understand. I am not saying that the media is bad. Sometimes they raise important issues and show much courage. But there is diminishing space for that. As a result, media is losing its credibility. That’s why corporate bodies are buying media houses. However, scepticism towards the media and towards politicians as a class is also increasing which can turn out to be healthy in the long run. In spite of all media support and propaganda, surveys show that the popularity of PM Modi is decreasing. This is also a country of oral communication; otherwise emergency would never have been lifted and BJP would not have lost the Delhi elections the way it did.

You have worked on the Bengal renaissance in which intellectuals played a sterling role. Do you think that caste and communal polarisations in the Hindi heartland are primarily because a renaissance never happened here?

The ‘renaissance’ took place in some other parts of India in other ways. The Bengal renaissance did not ensure the rise of the Shudras and the Dalits as in many other parts of India. Our problem now is different. We thought that politics will do the things not done by the colonial rulers. And no doubt, many major initiatives were taken from within the domain of politics. But the important politicians had come from the nationalist movement and were fully alert to the diversity of India. Academics was set up by politics. Politics allows us to have 30 national languages, despite the demand of many that there should be one national language. Now I see around me mostly prosperous overfed politicians or page-3 politicians; both equally arrogant, violent and corruption-prone.

Does it mean that vote politics is a hurdle in the process of democratisation and modernisation of the country?

No. It means that we have got a political class which is primarily rent-seeking. This type of contradictions are more visible in countries where politics becomes the main pathway to social mobility for those who were marginalised and disempowered for centuries. There is often a touch of deception in their attempt to succeed in politics and make sure that they are not displaced. For their survival and that of their families depends on that.

At present in the areas like arts, culture, and intellectual pursuits, there is an emergency-like situation. It has become increasingly difficult to express one’s views freely. For instance, many individuals including several prime ministers of the country have opposed the nuclearisation of India, but now more than 3,000 villagers in Tamil Nadu, mostly fishermen and farmers, are facing sedition charges because they were opposing a nuclear power plant in their midst. Most of them can’t even spell the word ‘sedition’.

Are you saying that our model of development is not sensitive enough towards villagers or marginalised people?

There should not be any confusion on this issue. The current model of development presumes that certain sections of people will have to make sacrifices. Whenever an elite wants a quick prosperity or modernisation, this has happened. Syngman Rhee in South Korea, Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan, Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, Mahathir Mohamad in Malaysia and Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore are not known for their commitment to democratic freedoms. Nor are the present rulers of China. Whenever a country tries to quicken the process of development, it releases or strengthens authoritarian forces. The present attempt to weaken the Land Acquisition Act is a step towards that. I am critical of conventional development and its collateral damages. I have every right to say so. No one becomes unpatriotic by saying this.

The BJP-led government is doing several things which the party had opposed when it was in opposition. What has happened to the ideology?

Data at our Centre (Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, CSDS) shows that only about 10 percent people vote for the BJP on ideological grounds. One survey shows that in Maharashtra, only about 7.5 percent voters support BJP and the Shiv Sena on the basis of ideology. And Maharashtra is supposed to be a base of Hindu nationalism. Actually, ideologies are not really important in this part of the world. They are becoming even less important now. People are jumping from Marxism to Hindu nationalism and from Hindu nationalism to Gandhism without batting an eye lid.

However, we can’t talk about ideologies as we did in the 1960s and 1970s. In most of the countries in the west, faiths are not strong enough and people have to depend on ideology to give a meaning to their life. But in a country like India, people derive their values from their faiths. So ideology is an instrument for them. Ideology is just a standard technology for politics, career-building and development.

How do you analyse campaigns like Ghar Wapsi or anti-minority speeches by several BJP leaders? Are they only fringe elements?

Yes. Fringe elements will always be there. They are only getting more exposure now. The sane do not get publicity; the lunatics and the fools do. It is a symptom of discontent in the society. Also, upper-caste Hindus are losing power because of the democratisation process. There is discontent among them, but they are much comfortable by saying that we are not discriminated as Brahmins, Kshatriyas or Baniyas, but as Hindus. You can see such displacements are there in other sectors too. We mistreated and exploited the tribals for 65 years and they have become the support base for Maoists as a result. Probably 90 percent of the Maoists today can’t even spell the word ‘Mao’, though it is not a difficult spelling. And our leaders also treat them just as the British treated them [by imputing seditious motives].

What is the ideology of our constitution then?

Actually Ambedkar was a brilliant legal mind and a classical liberal. Liberalism in other societies had other trajectories, but in India it had revolutionary implications. There is no scope of dictatorship of proletariat or their vanguards. He himself was a Dalit, but there is no scope for dictatorship of Dalits or Shudras either. The Indian constitution is ideologically open. You can call it trans-ideological.

What is your dream for India?

I want a compassionate, humane society. I want a society where values come primarily from empathy and compassion. Increasingly, that is becoming difficult. European enlightenment taught us that values should come only from reason. This undue emphasis on reason makes us look at statecraft as an expertise, as an impersonal, heartless profession. This is the main cause of our suffering. We are today willing to sacrifice millions of people and thousands of little cultures in the name of development. You cannot make an omelette without breaking an egg is what they say. India is becoming the homeland of millions of floating, newly proletariased people. They are seen as laboratory animals by development experts. I may not be a Gandhian but I consider Gandhi a much greater guide than Chanakya, who is adored mainly because he was a forerunner of Machiavelli. Gandhi is one of the most relevant thinkers.

But Gandhi was challenged by Ambedkar who was a great revolutionary, as you said. According to Ambedkar, Gandhi supported the oppressive caste system.

Gandhi believed in a non-hierarchical, occupation-based varna system; he did not believe in the intrinsic superiority of upper-caste lifestyles, which even many educated Dalits believe in. Gandhi wanted to convert Brahmins into Dalits and Shudras so that they could learn the dignity of labour. That is why the first task he taught his upper-caste followers in his Ashrams was the cleaning of toilets. I think there was something much more moving and philosophically grand in it than the efforts to emulate Brahminic or Kshatriya lifestyles

and, thus, give these lifestyles a new kind of legitimacy. The upper castes have reasons to be embarrassed about their past; the ati-shudras and the Dalits do not.

Several skills have survived by caste in India, so Gandhi was right when he tried to abolish untouchability first. He was clear that this is the responsibility of upper castes who have forced the lower castes to live in indignity.

feedback@governancenow.com

(This interview appears in the July 16-31, 2015 issue)