A new book attempts to preserve the fading memories of the institution in all its true colours – from its history and landscape to academics, library, canteens and politics

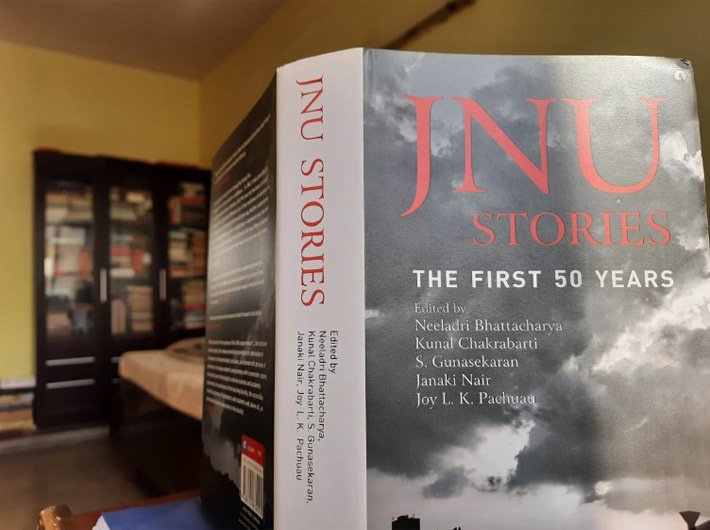

JNU Stories: The First 50 years

Edited by Neeladri Bhattacharya, Kunal Chakrabarti, S. Gunasekaran, Janaki Nair and Joy L. K. Pachuau

Aelph / xl + 468 pages / Rs 999

Many love it, some hate it, but nobody ignores it. The Jawaharlal Nehru University is a one-of-a-kind institution. On one hand, it has set high standards of academic excellence, as acknowledged by the National Institutional Ranking Framework of the Ministry of Human Resource Development (as it was formerly known). On the other hand, it is known as the most vibrant (of late, violent) ideological battleground of student politics. The JNU completed fifty years in 2019, and a group of scholars have come together to pay a rich tribute to the institution with a marvellous book.

Happily, ‘JNU Stories: The First 50 years’ is just like the institution it celebrates – polyphonic, multifaceted, argumentative, and joyful. For past students, it provides a handy shrine for nostalgic trips. Since the institution is undergoing a large-scale onslaught, this volume has a more serious job to do as well. “In documenting some aspects” of what Romila Thapar has termed as a part of India’s cultural heritage, the editors (all from the Centre for Historical Research) “hope to preserve memories that may be of use to all those who will, we hope, salvage and rebuild the institution, reinventing it to meet fresh challenges in the decades to come”.

Like India, the JNU is unique in a myriad of ways. For a university that sets the teaching and research agenda for numerous power-packed disciplines, it is blissfully unaware of its prestige quotient. This might be the only campus of its stature where English is not the lingua franca, and the mufassil is as much at home here as a firang. Be it the classroom or the hostel mess, there is a refreshing egalitarianism. Being mostly a residential institution means learning is not confined to lecture halls or the library, and the famous dhabas also serve as extension centres of continuing education. The JNU does not have bachelor’s level programmes (except in foreign languages), and the focus is more on doctorate-level research, which means the average age of the population is somewhat higher than at other universities (with predictable consequences for a residential institution). Situated in the southern ridge, the campus is blessed with the bounties of nature. There are rocky hills and even less-explored caves, where it would be difficult to believe you are in Delhi, or in twenty-first century.

Politics, yes, there is, and a lot – but usually in the sense of democratic practices, in which students can, for example, rejig the admission policy after long debates and a vote. Not only for the Left but for all elements of the political spectrum, the campus has been a training ground to learn the rudiments of democracy. After learning the ropes, many are known to move on to less red, greener pastures. Social media must have changed the scene, but for long decades, pamphlets and posters have been the preferred platforms of politics. Pamphlets on mess tables, pamphlets on water coolers, with more frequent editions than newspapers. Posters on red-brick school buildings, posters at dhabas.

As for academic itself – the first part of the JNU’s unofficial moto of ‘Study and Struggle’, there is a nearly enviable disregard for uniformity. Some centres (called ‘departments’ elsewhere) keep striving to raise the bar. Some of these are predictably housed in the two buildings of social sciences (history, for one), but many are low-profile buildings doing natural sciences too. With the semester format and continuous evaluation, the coursework absorption is smoother.

The rich fare in the hefty volume is divided in 12 segments, covering various facets, starting with the landscape and architecture, moving on to educational practices and memoirs, and it includes a few entries in Hindi (two poems, one with translation). The contributors are the veritable roll-call of the leading academicians and student activists but also some activists and some who came to study here from abroad and returned to their homes.

For those who have been part of this utopia, as Purushottam Agrawal puts it, this gem of a book will revive nostalgia. For those who haven’t – and yet are not prejudiced by the narrative coming from most sections of media, this will be a great introduction to the place. For all, it is an urgent reading in these critical times.