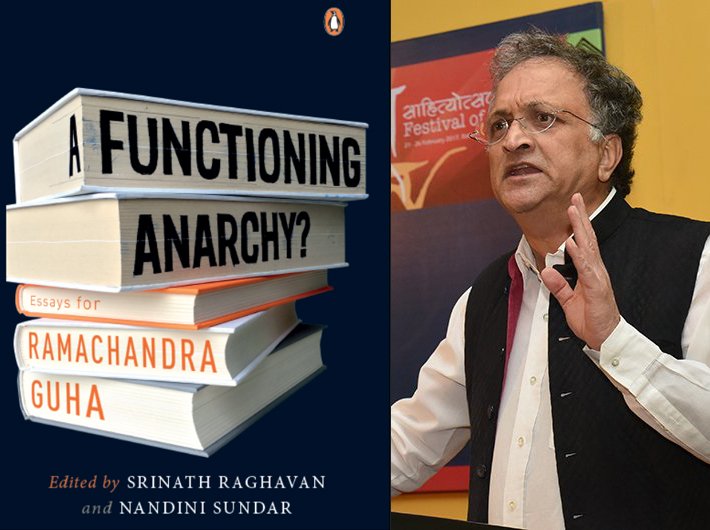

A Functioning Anarchy? Essays For Ramachandra Guha

Edited by Srinath Raghavan and Nandini Sundar

Penguin Random House India / 392 pages / Rs 650

In a long and versatile career spanning thirty-five years, Ramachandra Guha has produced a vast body of work. In each of his books, Guha has broken new ground: his pioneering environmental histories of India and his still relevant work on ecology and equity; his social histories of Indian cricket; his monumental history of the Indian republic; his biographies of Verrier Elwin and Gandhi; his anthologies of ecological, social and political thought in India; his collection of biographical and political essays.

Now, scholars Nandini Sundar and Srinath Raghavan have joined hands with some of India’s best known public intellectuals to put together a collection of essays paying tribute to Guha’s writings. The contributors include Arupjyoti Saikia, Shashank Kela, Kartik Shanker, Meera Anna Oommen, Amita Baviskar, Brototi Roy, Joan Martinez-Alier, and many others.

Here we reproduce from the book an excerpt of the essay by noted author and sports expert, Suresh Menon:

* * *

Yes, sports do count. But we are loath to concede that the traffic might also move in the opposite direction. It is easy to understand that sport affects economics or that it plays a significant role in the cultural development of a community. But history? No, that would be pushing it too far, we conclude, and move on to other things.

Three examples from sport, however, will help us understand sport’s impact on history better.

[…]

Historian Ramachandra Guha understands that sport affects not only the world around it but also the world that lies in the future.

The third example is of Palwankar Baloo, a left-arm spinner of ‘low-caste’ origin who led the Hindus and claimed over 100 wickets on the first all-India tour of England in 1911.

Guha’s ‘A Corner of a Foreign Field’ introduces us to Baloo, whom he calls the first great Indian cricketer. Baloo could not dine at the same table as his teammates at the Hindu Gymkhana when he started out. He had to drink his tea in a terracotta cup that was then shattered so others wouldn’t have to drink from it. Yet, his exploits on the field helped erase some of the prejudices against him and those like him, off the field. When he was dropped from the team, there was a public outcry.

On his return from the successful tour of England in 1911, a function was organized by the Depressed Classes of Bombay to felicitate Baloo. B.R. Ambedkar gave the welcome speech. Ambedkar would become the greatest of all ‘lower-caste’ politicians and reformers, and this was his first public appearance. Although later Baloo and Ambedkar fought on different sides in an election, the cricketer was the politician’s hero. In ‘A Corner of a Foreign Field’ Guha calls Baloo a ‘pioneer in the emancipation of Untouchables’.

In his book on cricket and race, Jack Williams asserts that race was at the heart of cricket throughout the twentieth century. In India, it wasn’t race so much as caste (and class, since the two moved in the same circles) that mattered.

Baloo played his last first-class match in 1920, and Palwankar’s brothers—Shivram, Vithal and Ganpat—also played for the Hindus, with Vithal breaking another barrier by captaining the team. If this were a work of fiction, this might be the place to tie it all up by asserting that since then, the caste system has been wiped out in India, that the successors of Baloo, like those who came after [Jackie] Robinson and [Basil] D’Oliveira, enjoyed the fruits of his work and are liberated.

Sadly, reality lacks the roundedness of fiction. But while admitting this, the efforts of those such as Baloo and Ambedkar, and the importance of those early steps, cannot be underplayed. ‘A Corner of a Foreign Field’ narrates the story with compassion. It could have been a classic of post-caste India, but it is still a post-colonial text and exciting revisionist history. The story was generally ignored by historians because of its origins in cricket, and by cricket writers because it seemed an obscure chapter in history. It took an exceptional writer to reach out between the two stools where the story seemed to have fallen, and bring it to our attention. Here finally was a historian who also wrote with understanding on cricket.

The large canvas helped Guha paint a history of India as told through cricket, rather than a history of cricket full of matches and runs and wickets. It asked—and answered—the question: How did this most British of games become so thoroughly domesticated in the subcontinent?

The sociologist Ashis Nandy had provided a glib, attractive one-line answer: ‘Cricket is an Indian game accidentally invented by the British’. He began his book The Tao of Cricket with this premise, but didn’t follow through.

For the social historian, says Guha, mass sport is a sphere of activity that expresses, in concentrated form, the values, prejudices, divisions and unifying symbols of a society. Yet, historians generally ignore it.

It has become a habit to connect the way a country plays its sport—soccer in Brazil, cricket in India—to its national character. When the Indian Ranjitsinhji was charming all of England with his batting at the turn of the twentieth century, he was so fresh, so daring, so original that a contemporary said he ‘never played a Christian stroke in his life’.

Neville Cardus, never one to hold himself back when describing a favourite player, wrote, ‘The light that shone on our cricket fields when Ranji batted was a light out of his own land, a dusky, inscrutable light. His was the cricket of black magic indeed. A sudden sinuous turn of the wrist and lo! The ball had vanished—where? The bowler knowing he had aimed on the middle stump saw as in a vision the form of Ranji all fluttering curves. The bat made its beautiful pass, a wizard’s wand. From the middle stump the ball was spirited away to the leg side boundary’.

It was easy for Ranji to inspire poetry. Talent apart, he was a prince, and therefore an exotic Eastern gentleman.

Baloo was at the opposite end of the exotic scale. He was an ‘invisible man’, to use the novelist Ralph Ellison’s evocative phrase. Princes were noticed. ‘Untouchables’ were not.

Sport has been viewed through various glasses. Marxists have their interpretations, Dalits too (some point to the number of educated Brahmins who filled the teams and ask if that is a commentary on the poor availability of education and infrastructure for the disadvantaged). But history hadn’t been looked at through the glasses of sport.

‘I do not support the placing of sports history in a ghetto of its own’, writes Guha. ‘The attempt should be to use ignored or previously marginal spheres, such as sport or gender or environment to illuminate the historical centre itself’.

Historian and cricket lover Guha’s favourites in the respective fields are both named Thomson. One with a P, as in the social historian E.P. Thompson, and the other without a P as in A.A. Thomson. E.P. Thompson has written about meeting Jawaharlal Nehru as a boy and being asked about his batting technique; A.A. Thomson has no such crossover story. Both were outstanding writers, but neither could have written ‘A Corner of a Foreign Field’. That needed a combination of the Thomsons, and an Indian who asked the question: What do they know of history who only history know?

[Excerpt reproduced with the permission of the publishers, Penguin India.]