What happens in prison, stays in prison – but scarred minds and tortured bodies bear those tales. Five case studies

Manjula Shetye’s death after a beating by jailors in Mumbai’s Byculla jail and even the riot that followed might have gone unnoticed by the media. It got the prime-time and page-one attention it did because a high-profile prisoner – Indrani Mukerjea – was involved in the jail riot. In July, Shetye was allegedly brutalised by women jailors and guards for protesting when breakfast for inmates in her ward was short of two eggs and some paav. Reports quoted witnesses telling investigators that Shetye was called to a jail officer’s room, where she was beaten. She returned to the ward in much pain. Later, some policewomen came to the ward and assaulted her again. Witnesses alleged that a lathi was shoved into her private parts, and she was left bleeding. After she collapsed in the bathroom, she was taken to a hospital, where she died.

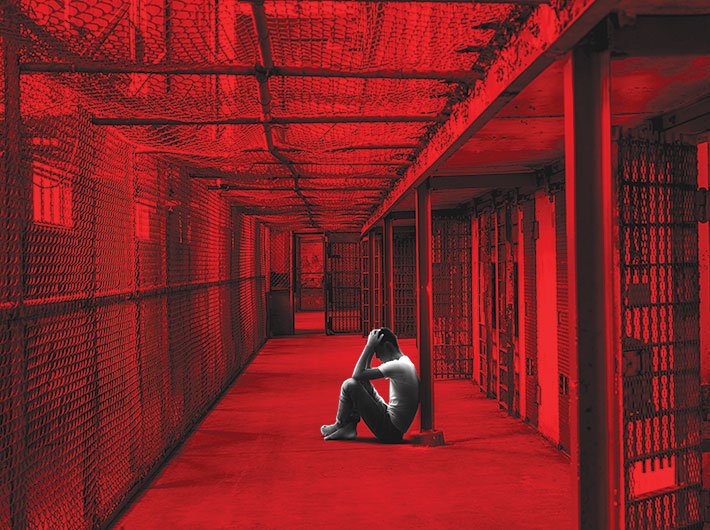

In modern, forward-thinking societies, jails are supposed to be places where convicted wrongdoers are isolated – that itself being punishment. But overcrowding, the attitudes of society and jailors to punishment, the long justice process, the absence of psychological counselling – all combine to make jails hellish. We look at some stories from jails, stories of people who have been there as undertrials or convicts and experienced unwarranted brutality of the kind that ended Shetye’s life.

ANGELA SONTAKEY

ANGELA SONTAKEY No questions!

Angela Sontakey, alleged to be a Maoist, had 18 cases against her, 16 of them filed in Gadchiroli area. She was lodged in transit in Nagpur jail before being brought to Byculla jail in Mumbai, where she spent five and a half years. “A person who is aware of his or her rights and asks questions is assaulted to let the lesson go across to others that no questions must be asked!” she says. She speaks of once being taken to a court in Gadchiroli, but being suddenly brought back to the barracks. “When I demanded to know why, different reasons were given. When I insisted on being taken to court, I was beaten with a baton, slapped and kicked by women prison officials in front of male officials,” she says. To protest, other Naxal co-accused went on a hunger strike.

She narrates how a jail guard came once hit a very pregnant Bangladeshi woman. When Sushma Ramteke, another co-accused, told her to stop, Ramteke was also beaten up. “That evening, she was again assaulted brutally, and male staff joined in the assault,” says Sontakey.

When a new woman jailor decided that women would be frisked in the barracks, Sontakey and others protested because the staff would steal their belongings. But the jailor told them this had been the practice since British times. “An African girl who wanted her belongings back was brutally assaulted,” says Sonatakey. “A majority of new recruits are nice, but they are trained to become rude and brutal over time. Senior staff instruct juniors to beat inmates with batons.”

The jail manual, setting out the routines of prison life and, is not given to prisoners, even when they ask to see it. “After I put in an RTI query on mobile jammers, whenever I went to the jailor I was taunted and told I was not cooperating with the jail authorities. Asking or requesting for something is seen as challenging the jail authorities and prisoners are beaten for it. We are told the jail manual is not for us. When I obtained a book setting out jail rules, it was confiscated. When the parliamentary standing committee on empowerment of women visited the Byculla jail in 2014, we had to shout to attract their attention. We requested them to help some women who were unable to raise money for obtaining bail,” she says.

She says magistrates or judges sometimes visit the prison, but no one dares to complain to them as they are accompanied by the jail staff. And only those prisoners who are in the good books of the jail authorities are presented to the judges. Complaint boxes are kept near CCTV cameras, so prisoners don’t have the anonymity to complain without fear of reprisal.

“Most judges only visit the circle office, sign and leave. A few good judges take note of prisoners’ complaints and instruct jail staff,” she says.

PRADEEP BHALEKAR

PRADEEP BHALEKARConstables give injections

Pradeep Bhalekar, who has served jail terms at the Thane and Arthur Road prisons under the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act (MCOCA) for four years, is now an activist running the Mahatma Gandhi Manav Adhikar Forum. He has taken up cases of police brutality and mistreatment of prisoners in jail, and had filed a PIL (since disposed of by the Bombay high court) in the Manjula Shetye custodial death case. “There’s a clear bias against ordinary prisoners,” he says. “While VIPs and those with money are allowed all kinds of lenience and the best treatment, the ordinary prisoner who needs urgent medical care is not taken seriously and treated as if he is pretending to be ill. Jails are required to have an MBBS doctor, but that rarely is the case. Sub-jails mostly make do with homoeopaths. At jail dispensaries, the same two-three medicines in stock are handed out for all kinds of illnesses. It’s common for constables to give injections to prisoners who are ill.”

Water, a basic necessity, is in short supply at most jails. “It’s available only for one-two hours daily. Only if you run for your turn will you be able to have a bath. Even here, there’s a hierarchy: preference for use of toilets and bathrooms is for gangsters and hardened criminals,” Bhalekar says. Fights break out invariably. The punishment for those picked up at random after a fight is ‘naalbandi’ or bastinado: the prisoner is trussed up or held by jail staff while his soles are caned or beaten with batons.

The isolation and the time prisoners have for reflection could be ideal for bringing about positive changes in their mindset, and hopefully their lives. But in prisons that rarely happens. Every addiction and vice is catered to for a price. “Drugs, liquor, cellphones, SIM cards and so on are smuggled inside by jail staff and made available for a price,” says Bhalekar. “Entire gangs are run inside and from prisons. New inmates and first-time offenders, called handi in prison slang, find themselves either succumbing to the demands of gangs or joining up with them for protection. Quite often, the younger among them are put to chores, such as washing clothes, or exploited sexually. All this happens with the connivance of warders.”

Undertrials are allowed one mulaqat (or meeting) a week with relatives for 20 minutes, but they are asked to finish within five minutes. Bribery works, though, to seek longer meetings or for anything else. In fact, Bhalekar says, jail staff run a parallel business: medical supplies are diverted for sale outside prison, while prisoners who need medicine are made to pay for it; supplies such as eggs, cigarettes and so on are sold for inflated prices.

These days at least some court appearances are conducted via video-conferencing. This is meant to save time. But while the magistrates or judges may pass an order within a couple of minutes, the clerks take their own time to transcribe it and send it across, says Bhalekar. Then it’s the turn of the jail staff to delay things. Should anyone complain, it’s naalbandi for him or her.

SHAMIM MODI

SHAMIM MODI‘Set her right’

One wouldn’t expect Shamim Modi to have had a prison experience, leave alone a bad one. The law professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, is also an activist, and it was in this capacity, in her fight against a timber mafia of Madhya Pradesh, that she found herself spending 23 days at the Harda and Hoshangabad jails (both in Madhya Pradesh). “A minister was hand in glove with the timber mafia and we had gone to court to file cases against some sawmill owners,” she says. But the powerful found a way to make things difficult for her. Twelve cases were filed against her (she has been acquitted in 11) and was arrested when the high court was going on vacation for two months. With no option for obtaining legal respite, she had to go to jail.

The Harda subjail was infested with bandicoots and mosquitoes, she says. Prisoners would get bitten by both. She says she requested the warden for a mosquito net, but was told she wouldn’t get it in that jail. “Later, I was taken to the Hoshangabad jail in the middle of one night, and those who delivered me there told the jailers, ‘Isko theek kar do (Set her right)’.” Three women from the jail staff started beating her up. “When I asked them not to do so, pleading that I was only working for the poor, they retorted that this was how things were in jail. The warden then called for a lathi and ordered the women to strip me.” After all, she says, the powerful had decided to get her into prison in order to teach her a lesson!

The dictum that undertrials are presumed innocent till proved guilty in court is nothing but a sham, she says. Powerful people, especially those in uniform, commit atrocities with impunity even outside jail. “So you can imagine what they must be doing inside prison, where no one is watching and you have no way to fight the system,” she says.

Women, especially those from poor families, have a really bad time in jail. Their health deteriorates. “I found that most women had gynaecological problems, mainly because they weren’t provided sanitary pads for hygiene during menstruation. Sometimes, women are told to make do with pieces torn from old blankets. Tribal women, who wear nine-yard saris, fashion a pad from one end of it. Afterwards, they wear the sari from another end, washing the soiled end and using it to cover their head so that it dries.”

Like everyone who has spent time in prison, Modi learnt how any question put to jail staff is seen as a challenge to their authority. “When they handed me some washing powder on a piece of paper, I asked how many days it was meant to last. The jailor was offended and said he knew I was inciting other prisoners and that he could file yet another case against me,” she says. “All kinds of threats and excuses are used. When I asked why I wasn’t being allowed to meet my lawyer, they said that I had been charged under the National Security Act and could only meet my lawyer after obtaining clearance from the district collector. When I asked for the jail manual, they refused to give it to me. Jail officials think it is their duty to punish you and that living conditions in jail are part of the punishment. So everything that can go wrong, goes wrong in jails. Belongings are stolen, articles handed over by relatives and friends to jail staff for delivery to prisoners never reach them.”

Modi, who is also a trained clinical psychologist, says the prison time-table is such that prisons could easily be run as Vipassana centres, and that meditation could be used as the means to bring about true correction, provided prisons are staffed with people who are sensitive, trained, and motivated and the atmosphere is congenial and enabling. “But in prison, no one speaks a sentence without swearing or using filthy language. Besides, there is no contact with the outside world. The system of prison visits, for checks and for providing prisoners a mode to interact with the outside world, must be improved. In practice, jail staff are always around when visitors come, so no one dares to complain. Even when a prisoner is produced in court, he knows better than to complain. Asked if he has faced any problems in custody, he will say no and sign and go.”

As she puts it, “When you are in prison, you don’t want to talk because no one is going to listen and you will be made to pay for it. And when you come out, you don’t want to remember prison or talk about it at all. Who would want to?”

SHABBAR AJMERI SHEIKH

SHABBAR AJMERI SHEIKHMoney-making cops

Shabbar Ajmeri Sheikh, 23, says he was picked up by police just like that. “I was standing with a group of boys at Mankhurd station (a suburb of Mumbai) in 2012, when a fight broke out between some of the boys with me. Some of them started hitting the others. One of the boys went to the police and accused us of snatching his money. I was picked up from my home along with six others and sent to Thane jail. There I was kept in the ‘baba room’ (meant for young prisoners) with 250 other boys. It was four and a half months before I could obtain bail and was released, and my Ammi (mother) had to end up spending over Rs 1 lakh. She had to use up all her savings and sold her jewellery. There were bribes to be paid to guards and jail officials so that I would be taken to court when the hearing came up,” says Sheikh.

The system never let him be after that. In 2015, he says, around the time of Navratri festivities, police picked him up for preventive detention. He was told he must come to the police station so that his signature could be taken. On reaching there, no signature was taken; he was dragged away and left at the Arthur Road jail. This time, after seven days, he was released on personal bond. Then, no one told him that there were some cases pending against him and that he would still be required to present himself before courts for some hearings. Then the cops struck again.

In 2016, they turned up with a warrant against him. His fault: he had not turned up for court hearings. “The policemen knew where I lived. So why couldn’t they have served the notices in the interving period?” he asks. He suspects they just wanted to make life tough for him and in the process make some bribe money. He says that this time, his mother pleaded helplessness. “She told me, ‘Son, there’s not a paisa at home; how will I get you released from prison?’ ” he says. In the end, his family and friends approached the Al Birr Foundation, a socio-religious voluntary group based in south Mumbai that works among Muslims. The foundation raised the Rs 10,000 bail amount for his release.

“Why would the foundation, which has a good reputation, have helped me out if they were not convinced that I was an innocent who found himself trapped in situation not of my making?” Sheikh asks. “I told the policemen, ‘Yes, in 2012, there was reason to believe that I may have made a mistake because I could not really prove I was not there when the fight took place. But why did you pick me up during Navratri in 2015? If you had told me I must leave the city (as part of externment process to check crime during festive seasons), I would have accepted that as my fate and left the city for some time.’ And the policemen then told me, ‘We have to show our superiors that we picked up so many people.’ ”

Sheikh has been out for eight months now, and he hasn’t received a copy of the judgment in his case yet. The lawyer needs to be paid his fees.

VARSHA

Fear psychosis

Varsha (name changed) is a former inmate of the Byculla prison, and was released a little more than a month after Manjula Shetye died there. Varsha, who had been arrested in a corruption case, has a masters degree in law and says she now wants to do a PhD on the condition of undertrials. “Most people in jail don’t have any legal help in jail,” she says. “Many of them don’t even know under what sections they have been booked, leave alone knowing whether the lawyers provided to them by the state are doing their work properly.” She says that many lawyers provided as legal aid to undertrials just collect their briefs, get some signatures done and that’s that – they don’t even go to court. “I’ve even mentioned this to the judges. If the honorarium is too low, they should rather not take up these cases. I’ve not heard of any legal aid lawyer winning a case for a prisoner,” she says. “Guards, too, play mischief.

Sometimes, they don’t take prisoners to court. Just because they are in a hurry to return home after finishing duty, they don’t present a prisoner in court and ask for another hearing date.” All this, she says, adds to the travails and prolonged incarceration of undertrials.

Of the conditions in jail, the less said the better, she says. Quite often there would be no water for up to five days at a stretch and many women would be forced to go without a bath. Sometimes, she says, inmates are forced to drink water supplied for use in the toilet. At the Byculla prison, when she was there, she says, there was just one bucket and two mugs for a group of some 50 women. Since many are forced to do without baths, skin disease is common. There is no segregation of patients with infectious diseases like TB, so it’s common for prisoners to end up with diseases they did not have when they went to jail. And of course, there’s hardly any medical care. “Even the water filter, meant for some 450 prisoners, was kept near the toilet,” she says. “Just before a visit by some women MPs, after Manjula’s death, they changed the toilet doors and improved food and water supply, changed our bedsheets, but within a week of the visit, things returned to the same old condition.”

Inside a prison, the jailor is all-powerful. This allows jailors to get away with a lot, so they behave in a high-handed fashion. According to Varsha, it was such high-handedness on part of jailor Manisha Pokharkar that resulted in Shetye’s death. Pokharkar is an accused in the custodial killing of Shetye.

“Pokharkar would never listen to any of our grievances. She wouldn’t even allow us to talk among ourselves. She had created a fear psychosis and warned us not to make any requests when the superintendent came for weekly inspection rounds,” she says. “Shetye was quite good at yoga, and we would all go to her to learn yoga. This Pokharkar did not like. Also Shetye knew all the jail rules. One day, Shetye was moving about with a swollen eye. Everyone said Pokharkar had hit her. When I asked Shetye, she didn’t say anything, only the tears welled up in her eyes. She had a lot of self-respect.”

Varsha says that she had seen Shetye being dragged away by five women officials, but did not dare to stop them because she had seen another girl, Fazleen, being beaten brutally with belts, batons and chappals by 15 officials. Her fault: she had obtained some non-vegetarian fare from outside jail. “For three days, Fazleen was not taken to hospital. She was then taken to hospital on condition that she would not open her mouth,” says Varsha. “Fazleen had been in jail only for six months and maybe she hadn’t been weakened yet by jail food so she survived the beating and the brutality. Shetye, on the other hand, had spent 13 years in jail.”

geetanjali@governancenow.com

(The article appears in December 15, 2017 issue)