The crisis will persist as long as policymakers continue to view nutrition and food security in terms of subsistence and survival, of filling the stomach, and not in terms of good health or wellness

The union cabinet has approved setting up of a National Nutrition Mission (NNM) with a three-year budget of Rs 9,046.17 crore commencing from 2017-18, states a press release of December 1, 2017. From the limited information available in the public domain, it appears that the mission is not conceptualised as an executive kind of mission, like the National Health Mission, with a comprehensive strategy, roadmap, objectives, need-based interventions, and innovation in service delivery. Rather, its mandate appears to be to monitor, supervise, fix targets and guide nutrition-related interventions across the ministries; “map various schemes contributing towards addressing malnutrition”, introduce robust convergence mechanisms, ICT-based real-time monitoring system, digitalisation of the anganwadi, social audits, nutrition resource centres and jan andolans.

This way, the NNM looks more like a Mission for Measurement of Malnutrition, or some kind of an apex committee for national nutrition monitoring. No hint is given as to the methodology, additional manpower for the new grassroots work, or any institutional mechanisms to achieve the objectives, except that the implementation strategy would be based on intense monitoring and ‘convergence action plan’ right up to the grassroots level.

Clearly, this is at wide variance from what was announced in the finance minister’s budget speech on July 10, 2014, that “A national programme in Mission Mode is urgently required to halt the deteriorating malnutrition situation in India, as present interventions are not adequate. A comprehensive strategy including detailed methodology, costing, timelines and monitorable targets will be put in place within six months.”

The mission appears to be based on the premise that no new nutrition or nutrition related interventions are required, that there is “no dearth of schemes directly/indirectly affecting the nutritional status of children (0-6 years), and pregnant and lactating mothers”. Nutritional levels in the country are high because of “lack of creating synergy and linking the schemes”, and that “NNM through robust convergence mechanism and other components would strive to create the synergy”. It believes that malnutrition will reduce if targets are set, and achieved through convergence, synergy, real-time digital monitoring and measurement of malnutrition.

It is disappointing that the mission does not even enquire into, leave alone address, the reasons why improvement of our nutrition indicators across the board is so tardy. To ask a few questions: Why has the proportion of underweight children dropped by only 6.8% between NFHS 3 and 4, when per capita income has almost quadrupled during the same period; why has wasting and severe wasting increased by around 3%? Why do more than 50% of our women and children continue to be anaemic, when the national nutritional anaemia prophylaxis programme has been in operation since the 1970s?

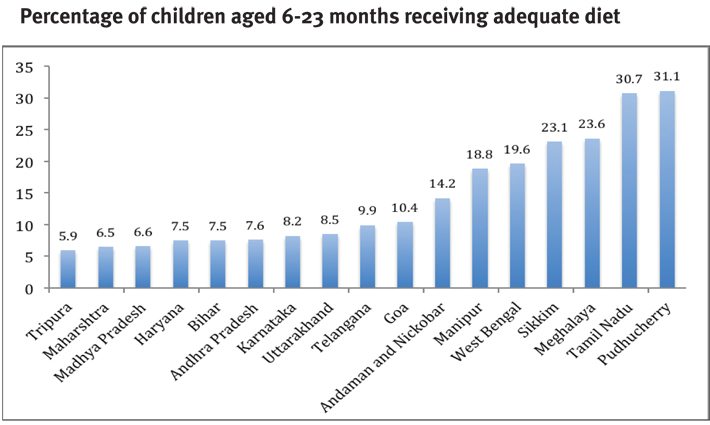

And most disturbing is the latest NFHS 4 data that only 9.6% children between 6-23 months (11.6% in urban areas and 8.8% in rural areas) receive adequate diet. The accompanying chart, extracted from NFHS 4 Factsheets (2016-17), is a direct snapshot of the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), the only scheme in our country with a nutrition supplementation component for children below six years, which has been in operation for more than five decades.

Adequacy of infant nutrition, whether through supplementary nutrition from the anganwadi or in the household, is squarely the mandate of the ICDS. At the anganwadi, this involves the supply of protein calorie micronutrient enriched supplementary food, and at the household it involves providing information to trigger behavioural change about timely and adequate complementary food for infants. Judging from the chart, the present interventions have failed on both counts, resulting in loss of zillions of brain cells of infants, and preventing them from attaining their full potential of muscle and height, a burden carried for life.

And we must realise with due seriousness that this refers to our demographic divided, our future work force, on whom we depend for future economic growth. Clearly, the present interventions are not working, neither at the anganwadi, nor in the households. And it is unlikely that inadequacy in infants’ diets will be addressed through digitalisation and target setting. It can only be addressed through adequate and timely complementary feeding, for which existing interventions have failed, and the NNM offers no transformational strategy shift or new interventions.

The data mentioned above is specifically about adequate diet of children under two years, and not about undernutrition, stunting or wasting, which have a combination of causes of dietary deficit, diarrhoea, worm infestation, infection, poor sanitation, unsafe drinking water.

The NNM states no intent to acknowledge, analyse or address the significant protein-calorie-micronutrient deficit which afflicts at least 50% of our population of all age groups and both genders, even after implementation of our major food programmes, viz., ICDS for four decades, midday meal programme for two decades, and the public distribution system (PDS) since the early 1980s. This has been adequately brought out in the

NNMB repeat surveys, the last being ‘Diet and Nutritional Status of Rural Population: Prevalence of Hypertension and Diabetes among Adults and Infants and Young Child Feeding Practices’ (2011-12).

The mission does not even acknowledge this fact, let alone develop strategies to address India’s great dietary deficit.

‘Popularisation of Low Cost Nutritious Foods’, an intervention mandated by the National Nutrition Policy, 1993, [Section V (iii)] to bridge this dietary gap, could have brought about sustained reduction of India’s malnutrition over time. But even today, this remains an orphan subject, not being the responsibility of any ministry. It is precisely because no low cost nutritious foods are available in the market that the poor of all age groups are unable to bridge their calorie-protein-micronutrient deficit, particularly the most vulnerable, leading to morbidity, lower productivity and incomes, and perpetuating the cycle of poverty. Monitoring or convergence by the NNM is good, but can it substitute for the hard macro and micronutrient requirements to bridge the dietary deficit?

This dietary deficit is compounded by an information and knowledge deficit in the household about basic dietary practices for children, adolescents and mothers, for example, what is a balanced diet within limited budgets, the age at which an infant should be given complementary feeding, proper growth of adolescent girls and boys, adequate pregnancy weight gain, importance of sanitation. Knowledge deficit is highest among the most vulnerable, viz., agriculture/construction labour families, where almost all wasted children are found. India’s malnutrition could reduce much faster had the NNM worked out a strategy for bridging both the dietary and information deficit in households through an effective nutrition education campaign reaching the most vulnerable households. Unfortunately, the NNM ignores them both.

Behaviour change and dietary diversification by providing information and awareness at the community/family level is something that has repeatedly been recommended – right from the Bhore committee report of 1946 and the first five-year plan onwards. However, this very powerful intervention continues to elude a strategy and programme even after six decades. Evidence from the Karnataka Multi Sectoral Nutrition Pilot Projects establishes that just behaviour change over a period of one year can bring about 3-4% decrease in underweight and wasting of children, improvement of adolescent girls’ BMI, pregnancy weight gain, and reduction in low birth weight. Unfortunately, the NNM has not marked this as a priority objective.

The inter-generational aspect, too, linking underweight and undernourished adolescent girls with underweight, malnourished mothers, who give birth to either low birth weight or malnourished babies, is also completely ignored. The adolescent girl is the critical link in the inter-generational, lifecycle and holds the key to the nutritional health of the next generation. The midday meal programme is the only nutrition programme for the school-going girl child between the age of 6 to 14 years, but it is a substitute meal worth about Rs 7 per day, not an additionality to bridge the calorie-protein-micronutrient deficit. The Sabala programme was introduced in 200 districts in 2011, but its coverage and nutritional component is weak. Most importantly, there is no mechanism at the village level that ensures that interventions for the nutritional needs of the girl child, the adolescent girl and the expectant mother operate in continuity and simultaneously – the only strategy that can break the inter-generational cycle in the shortest time.

Without having identified and addressed the root causes of undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies of more than 50% of the population, it is no surprise that our Global Hunger Index ranking has dropped from 97 to 100 in 2017, or that India’s nutritional situation is termed as ‘serious’ both in the Global Nutrition Report as well as Global Hunger Index. As long as nutrition governance and stakeholders continue to view nutrition and food security in terms of subsistence and survival, of filling the stomach, and not in terms of good health or wellness, the situation will persist. Nutrition security is a subject that has not even entered into the realm of public debate.

Addressing the causes of India’s malnutrition, as described above are doable and have been done in the pilot projects in the two most backward blocks of Devadurga in Raichur district and Chincholli in Gulbarga district. The nutritional status of children, adolescent girls and women has improved dramatically through behaviour change and additional dietary supplementation, strategic and practical convergence and real time monitoring. To know more about it, take a look at www.karnutmission.org.

Just before announcing the NNM, the ministry of women and child development took a rather disturbing decision. On November 23, it informed the states that it was discontinuing several administrative costs of the ICDS from December 1, 2017, and reducing the central share for staff salary to 25% from the existing 60%. This is bound to cause serious financial dislocation in the states, just as the financial year is ending. Not a very encouraging start for the NNM – or whatever is left of it.

Rao, IAS (Retd), is advisor, Karnataka Comprehensive Nutrition Mission. Views are personal.

(The article appears in January 31, 2018 edition)