Donald Trump’s unexpected victory in the 2016 presidential elections has unleashed a great deal of soul searching among America’s liberal elite. His victory has been attributed to anger and discontent among those whom Hilary Clinton, in a rare moment of indiscretion, chose to call “the deplorables”: mostly poorly educated working class white voters, often born-again Christians, who feel increasingly marginalised in 21st century America, and whom Trump effectively wooed with vague promises of making America great again.

The reality is more complex. Clinton after all won the popular vote by a larger margin than any presidential candidate who did not win the electoral college vote. And she lost the electoral college because she lost three key states (Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin) by a tiny margin. Exit polls show that Trump won by about the same margins as his predecessor, Mitt Romney, in 2012, in three key traditionally Republican constituencies: non-Hispanic white voters, women and the elderly. Where Trump triumphed was among non-college whites, winning a record two-thirds of their vote. He also did well among middle-class voters in key states, and in areas where there were large concentrations of factory workers.

Trump’s populist campaign successfully played on the fears and racial prejudices of whites, who see their jobs threatened by free trade and open immigration policies, and who identify immigrants with drugs and crime. He committed himself to shut down illegal immigration, restrict immigration of Muslims from nations with a record of terrorism, and withdraw from trade treaties which he saw as taking away jobs from America. These fears and the underlying anger and violence that marked the election reveal a deeper American crisis that has not received the kind of attention from the media that it surely deserves.

The Great American Crisis

The 20th century was undoubtedly an American century. Following a period of isolationism, a nation made up largely of European immigrants led the Allies to victory over the Axis powers, and emerged by the middle of the century as the world’s most powerful military and industrial power. America then led the efforts for recovery from the War in Europe and Japan, helped establish a set of global governance institutions, and positioned itself as the self-proclaimed “leader of the free world”. The 20th century saw massive changes in the US. Its population quadrupled over the century from 76 million to 282 million. Its GDP today, at just under $18 trillion, represents more than a fifth of the global GDP. Americans understandably see this huge transformation under a democratic constitution, a multicultural, multi-ethnic society, as evidence of American ‘exceptionalism’.

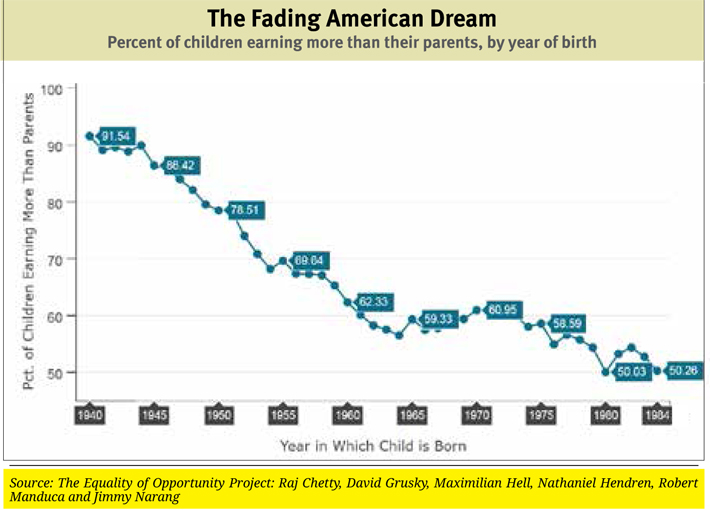

However, by the end of the last century, some cracks were emerging in this rather remarkable transformation. The American dream is proving increasingly elusive to large numbers of people. The US election revealed the frustration that ordinary Americans are feeling at the growing gap between the dream that anyone born in America can succeed if they really tried and that children will grow up to do better than their parents, and the hard reality that they face each day trying to cope with stagnant real incomes and rising wealth and inequality. At least three sets of rapid changes in the US are driving this resentment and frustration:

1. Foreign competition and technology impacting jobs and real wages

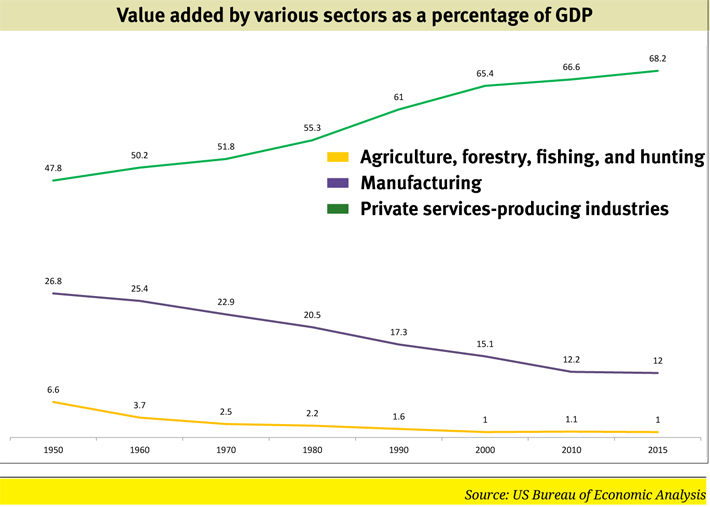

First, the 20th century saw the United States transform from a predominantly agricultural economy in 1900, to a manufacturing economy by 1950, and to a predominantly services economy by 2000. Thus, in the space of three generations or less, the average American worker has had to transform and reinvent herself from being a farm labourer to a factory worker to working in the service sector. Rapid change is itself a source of stress, as we are also seeing in India.

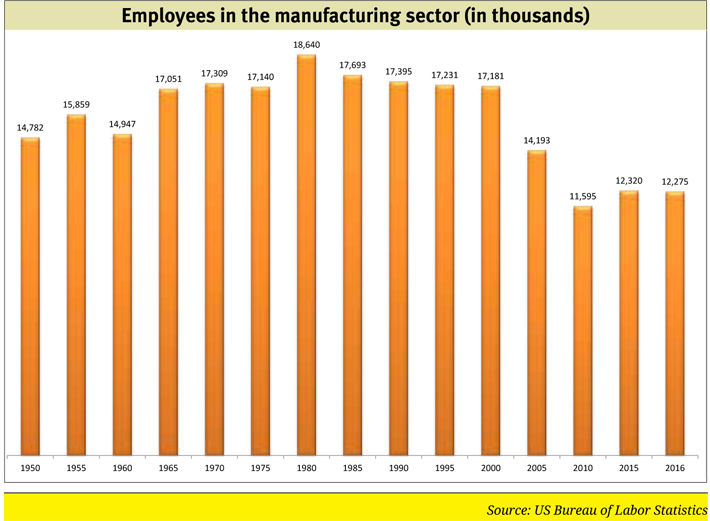

Employment in manufacturing, which peaked at 19 million in 1980, has fallen by 2016 to around 12 million. As a result of competition from China (as reflected in the large US trade deficit in manufactured goods with China) and from other low-cost producers, technology-induced reduction in employment opportunities, and relocation of plants overseas to reduce labour costs, workers face retrenchment and must learn to reinvent themselves or face unemployment. Safety nets are short-term in nature, and there are few retraining programmes.

A related trend is a steady decline in trade union membership from a peak of 21 million in 1979 to some 13 million in 2015. More than half of all members are public sector workers, with over one in three public sector workers unionised as against just one in 14 of private sector workers. Unionised workers in general command better salaries and working conditions.

Given labour market conditions, it is not surprising that real wages are stagnating. A Pew Research Center study of government wage data over five decades reveals that “for most US workers, real wages – that is, after inflation is taken into account – have been flat or even falling for decades, regardless of whether the economy has been adding or subtracting jobs… today’s average hourly wage has just about the same purchasing power as it did in 1979”.1 A 2014 Pew survey cited in this study also found that 56 percent of Americans said their family income was falling behind the cost of living while more than a third said their income was just about staying even with inflation.

2. Poverty deepens and income inequality rises

The Great Recession of 2008-09 worsened the conditions of the poor. The Wall Street Journal reports that some 9.3 million households lost their homes as a result of foreclosure by banks. Banks failed to do due diligence before making these loans. Many victims of foreclosure moved to areas of concentrated poverty (where 20 percent or more of residents are poor). Thus, according to the US Census, one in four Americans (some 77 million) live in these poverty areas, up from one in five in 2000. Bread for the World Institute argues in its 2017 Hunger Report that housing costs are at the centre of concentrated poverty. “Housing consumes the largest share of a low income family’s budget, effectively dictating where the family lives.” Rising rents and utility bills have accompanied foreclosures, further squeezing a poor family’s budget and forcing upon them the unenviable choices between eating and paying rent.

Researchers have shown that those who live in concentrated poverty neighbourhoods, whether or not they are poor by official definitions, are trapped in a downward spiral due to high crime rates, declining standards of teaching in state schools, high dropout rates from schools, and poor healthcare, all of which help prolong poverty for those who are already poor and suck into poverty those who aren’t. While the vast majority of residents in these poverty neighbourhoods are from the minorities, about one-fifth are whites.

Stubborn poverty is accompanied by rising inequality. A recent paper2 by Thomas Piketty, author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, and two fellow researchers reveals disturbing findings from their new series on the distribution of national income. While the average national income per adult grew by 61 percent in the US as a whole between 1980 and 2014, “the average pre-tax income of the bottom 50 percent of individual income earners stagnated at about $16,000 per adult after adjusting for inflation”. However, income rose by 121 percent for the top 10 percent, 205 percent for the top 1 percent and 636 percent for the top 0.001 percent. Much of this reflected increased dividends, due to high corporate and financial sector profits and high senior management salaries. For the bottom half of the working age population (adults below 65), incomes actually fell. Research by the same authors suggests that wealth inequality has worsened even more.

Given these trends, it is not surprising that the American dream, that children have a higher standard of living than their parents, is not being realised. Raj Chetty, professor of economics at Stanford University and a recipient of the John Bates Clark medal for the best American economist under age 40 (and awarded a Padma Shri in 2015), together with fellow researchers has just published a paper3 that attempts to measure absolute income mobility, defined as “the fraction of children earning or consuming more than their parents”. Using data for parents and children of the 1940-84 birth cohorts, they find that absolute mobility declined on average from 92 percent for children born in 1940 to 50 percent for children born in 1984. The decline occurred for children from both low- and high-income families, in all states and for sons and daughters. The decline is attributed principally to the unequal distribution of economic growth.

3. In less than three decades the US could become a ‘majority-minority nation’

As noted above, the United States is a nation of immigrants. Starting with the early settlers at the beginning of the 17th century whose numbers grew to quickly overtake a small American Indian population, the United States maintained an open door policy for much of the 19th century. Indeed, the words inscribed on the base of the Statue of Liberty symbolised the nation’s attitude to immigration:

“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Those escaping the Irish famine and tyranny of various forms in Europe and elsewhere bore witness to this. New laws enacted in 1919 and 1924, motivated by a desire to restrict non-European immigration, greatly slowed down immigration for the next four decades. In 1965, president Johnson opened up the doors to immigrants once again, putting in place immigration policies that encouraged skilled immigrants, emphasised family reunification, and opened doors to immigration from Latin America and Asia. A Pew study4 estimates that some 59 million immigrants arrived in the US in the fifty years through 2015. More than one half are from Latin America, with Mexico being the largest contributor, and a quarter from Asia. Interestingly, India has emerged as the third largest source of migrants in the 1965-2015 period (some 2.7 million migrants), next to Mexico (16.3 million) and China (3.2 million).

What President Obama said on rising inequality

But for all the real progress that we’ve made, we know it’s not enough. Our economy doesn’t work as well or grow as fast when a few prosper at the expense of a growing middle class and ladders for folks who want to get into the middle class.

That’s the economic argument. But stark inequality is also corrosive to our democratic idea. While the top one percent has amassed a bigger share of wealth and income, too many families, in inner cities and in rural counties, have been left behind.

The laid-off factory worker, the waitress or healthcare worker who’s just barely getting by and struggling to pay the bills, convinced that the game is fixed against them, that their government only serves the interest of the powerful – that’s a recipe for more cynicism and polarisation in our politics.

From Obama’s farewell speech on January 10

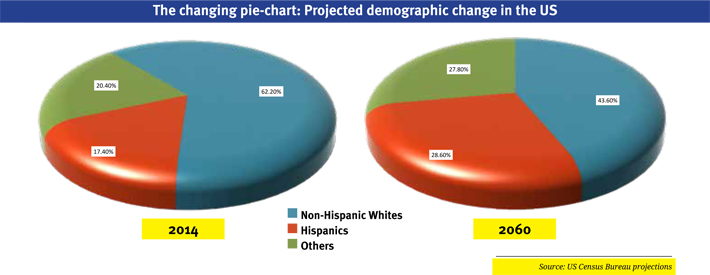

This large migration since 1965 has caused the share of non-Hispanic white Americans to fall to some 62 percent by 2014. The US Census bureau projections5 show that on present trends, the population of non-Hispanic whites alone will comprise less than half of the nation’s population by 2044, which the authors describe as “the point at which we become a majority-minority nation”. While the Hispanics will be the largest single group among migrants, “the United States will become a ‘plurality’ of racial and ethnic groups”, the authors argue. This prospect is a major source of the anti-immigration sentiment that dominated the 2016 elections, with Trump pledging to build a wall between the United States and Mexico to stop the flow of illegal immigrants. A survey carried out by the Pew study found that half of the respondents blamed immigrants for the state of the economy and crime, and found respondents particularly negative about Hispanic immigrants.

Prospects for change

The 2016 election has exposed the underbelly of the US economy and demonstrated the unwillingness of leaders of both political parties to address the underlying causes of the issues driving the growing crisis described above. The failure to manage the rapid changes in the economy through social policies, to invest adequately in health and education to help ordinary American families manage these large changes, to devise tax and expenditure policies that reverse growing inequality, and to find the resources to invest in a rapidly deteriorating infrastructure are all contributing to growing cynicism and a total loss of trust in government and politicians. As a result, non-college educated white voters in particular believe in less government and fear “big government”.

The Republicans have encouraged this distrust in government. The Democrats have failed dismally to persuade ordinary Americans that they need to not vote against their own class interests. Until this election, the establishments of both political parties saw it in their interest not to address inequality. That highly effective lobbyists for corporate and financial interests have persuaded them not to do so is an aspect of governance that Indians know all too well.

It took a rank outsider like Trump to expose this underbelly. His unorthodox campaign cleverly and cynically exploited this uncertainty and resentment among white American voters. Their vote for Trump was not so much a belief in his ability to solve their problems, although many clearly thought he would, but a cri de coeur, a strong signal to political establishments in both parties that enough was enough. It will not take long to find out if anyone is really listening.

Lateef specialises on issues of governance and development.

(The article appears in the January 16-31, 2017 issue)