Democracy is people’s own rule, but the billion-plus people of India cannot gather in one place to frame laws. So we elect representatives who, theoretically speaking, draft laws on our behalf. In practice, much can get lost in translation. A single member of parliament cannot be expected to read the mind of 10-20 lakh people. What is needed is a process of law-making that better channelises what people want. The petition system is the answer.

Any sufficient number of people can sign a petition asking the parliament, or the local member of parliament, to consider their proposal, and the receiving side is duty-bound to respond to it. The proposal eventually will be put to vote – just like regular bills. In a way, the idea is not dissimilar to the notion of referendums or plebiscite, in so far as it involves people directly in the process of democracy. In other words, it is direct democracy in action.

It is not at all idealistic: the petition system is in place in countries like Canada, Australia and New Zealand. In recent times, BJP MP Varun Gandhi has advocated it here, in the form of a system of e-petitions.

Think

If the whip system is done away with, MPs can vote according to conscience

. . .

The ruling dispensation should encourage private members’ bills

. . .

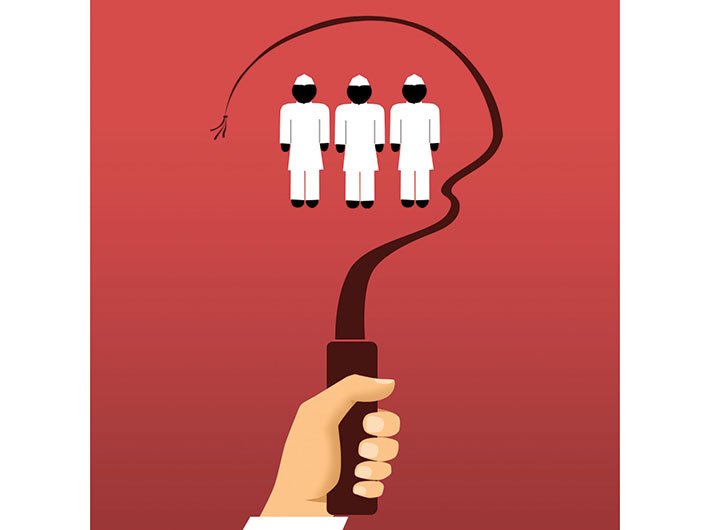

People can initiate law making with formal petition to authorities

However, the petition system and direct democracy would be asking for the moon, when we do not have even simpler measures in place. Here are two of them: allowing MPs to vote as they deem fit, and allowing MPs (outside the government) to propose laws.

Following the British tradition, we have in place the whip system, which means every MP has to vote according to the party diktat. Though technically the whip (the very word has the wrong connotations) is issued only for bills whose outcome may affect the government (especially the finance bill), the parties ask MPs to toe the given line more often than that. It has been proposed frequently that barring the finance bills, which if not passed would lead to the government’s ouster, MPs should be allowed to vote according to their conscience – just as they can in the presidential elections. If allowed, such a situation can empower individual MPs. Debates too would rise above party lines and bipartisan consensus can develop on some issues. The way things are means an MP is merely a number and only five or six party bosses control the proceedings in parliament.

Secondly, all the bills passed by parliament are invariably coming from the government. There is a provision that ‘private members’ (that is, all MPs who are not part of the cabinet) can propose bills. In the last year, Jairam Ramesh and Subramaniam Swamy have been in the news for proposing bills. Rajya Sabha has passed the transgender bill proposed by a private member, which is yet to be discussed by the Lok Sabha. Historically, however, private members’ bills are rarely even discussed in the house, much less passed. The last time a private member’s bill became a law was back in 1967. This shortcoming reduces an MP to a number.

These measures can make democracy more representative of the people’s will. There are many other measures prescribed for the same purpose. We could perhaps make a beginning by at least acknowledging that we need to move in that direction.

Reality check

A major roadblock in deepening democracy in India is in numbers. The humungous population numbers, coupled with diverse and entrenched interest groups, means direct democracy is not a feasible idea here. As for doing away with the whip system and taking private members’ bills seriously, the only hurdle seems to be the power play.

(This article appears in January 15, 2019 edition)