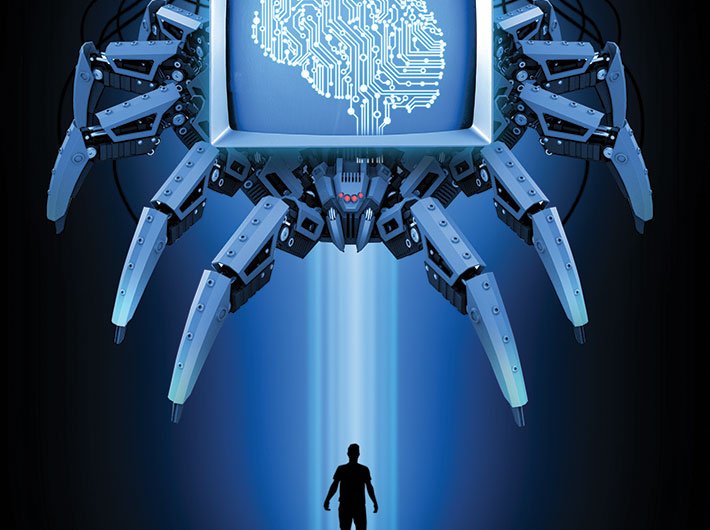

If the Global South does not assert control over how AI is built and deployed, it will remain at the mercy of superpower competition

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is often hailed as the great equaliser, a technology that can democratize knowledge, drive economic growth, and help societies leapfrog development. In the Global South, governments and companies alike see AI as a tool to close the gap with advanced economies. India, for instance, speaks of “AI for All,” positioning itself as both a market and a hub for AI innovation.

Yet, beneath this optimism lies a stark reality: AI is not neutral. In fact, it is already replicating, and in some cases deepening, longstanding inequities. In India, AI models are casteist, systematically reinforcing hierarchies that marginalised communities have struggled against for centuries. At the same time, global surveys reveal that ordinary people remain shockingly unaware of how biased and unregulated these systems are. And in the broader geopolitical landscape, the Global South risks becoming an arena for technological competition rather than an empowered actor shaping AI on its own terms.

The Caste Code of AI

A recent investigation by researchers under the DeCaste framework (https://arxiv.org/html/2505.14971v1) has exposed how large language models (LLMs), the backbone of AI tools like ChatGPT, tend to mirror India’s entrenched caste system. These models disproportionately favour upper-caste narratives while sidelining Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi experiences. Even when prompted with neutral or inclusive queries, the answers skew toward dominant caste assumptions, embedding inequality into seemingly objective outputs.

This bias is not accidental. LLMs learn from vast amounts of online text, much of which comes from digitally empowered groups, largely urban, male, and upper caste (https://arxiv.org/pdf/2309.08573). In a country where nearly half the population still lacks internet access, the perspectives of marginalised communities are systematically underrepresented. When AI systems generate content, they amplify these gaps, reinforcing who gets seen as “normal” and whose knowledge is rendered invisible.

The consequences go far beyond academic debates. AI tools are increasingly used in education, hiring, content moderation, and even governance. If the data and models themselves carry caste bias, then technology becomes another instrument of exclusion, this time under the guise of objectivity.

A Public Blindspot

Despite such risks, consumer attitudes toward AI remain surprisingly uncritical. According to Kantar’s recent report on sustainability and technology, people across the world, especially in emerging economies, tend to view AI with more hope than fear (https://www.kantar.com/inspiration/sustainability/social-fears-climate-hopes-the-consumer-view-on-ai). While there is some concern about privacy, misinformation and job loss, the deeper structural biases of AI remain largely invisible in public consciousness (https://scroll.in/article/1055846/indias-scaling-up-of-ai-could-reproduce-casteist-bias-discrimination-against-women-and-minorities?utm_source=chatgpt.com) .

In India, this ignorance is particularly dangerous. People may assume that because AI is “scientific” or “rational,” it is free from prejudice. Yet as caste bias in LLMs shows, AI merely reflects the society that produces it. If the general public does not question these biases, pressure on companies and governments to reform AI systems will remain weak. The risk is a widening gap between those who understand AI’s inequities and those who use it blindly, reinforcing them.

AI and the Global South: Whose Innovation?

This problem is compounded by global geopolitics. As the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) notes, AI development in the Global South is unfolding within the shadow of strategic competition between the US and China (https://www.csis.org/analysis/open-door-ai-innovation-global-south-amid-geostrategic-competition). While countries like India, Brazil and Kenya aspire to leverage AI for local needs, whether in agriculture, education or healthcare, their technological ecosystems remain heavily dependent on infrastructure, tools, and standards created elsewhere.

This dependency means that bias baked into global models travels into local contexts. For example, a model trained primarily on English-language, Western-centric data is ill-equipped to capture the complexities of caste in India. Even when local researchers attempt to audit or retrain such models, they are constrained by access to capital, compute, and policy influence.

Unless the Global South asserts its agency in shaping AI, through regulations, independent datasets and South-South collaboration, it risks becoming a passive consumer of technologies designed elsewhere, technologies that do not account for local histories of inequality.

Building a More Just AI Future

If AI is to serve as a tool of empowerment rather than exclusion, three urgent shifts are needed.

First, AI must be audited for caste and other structural biases. Just as gender and racial bias have become focal points in global AI ethics debates, caste must be explicitly recognised as a category of harm in India and other South Asian contexts. Policymakers should mandate bias testing across socio-cultural, educational, and economic dimensions.

Second, local voices must be integrated into AI design. It is not enough to build datasets in Silicon Valley and apply them in Delhi. India needs investment in community-led data collection, representation of marginalised groups in AI research, and public consultation on how AI should be deployed in sensitive sectors.

Third, the Global South must chart its own AI strategy. This means going beyond being a “market” or “talent pool” for Western firms. Countries like India must collaborate with other developing economies to create independent research networks, shared data infrastructures, and ethical frameworks rooted in their social realities, not borrowed from the West.

Conclusion: Beyond Blind Optimism

The promise of AI in the Global South cannot be separated from its risks. In India, where centuries of caste oppression continue to shape opportunity and identity, AI risks hardcoding those inequalities into the digital age. If the Global South does not assert control over how AI is built and deployed, it will remain at the mercy of superpower competition.

The Kantar report is right to note that people remain hopeful about AI, but hope without scrutiny can be dangerous. We must resist the temptation to see AI as a magic bullet. Instead, we must confront the uncomfortable truth: AI is already casteist, biased, and unequal. The task now is to ensure that technology does not merely mirror our worst hierarchies, but helps dismantle them.

Nidhi Singh is a Delhi-based researcher, and her research passions encompass Feminism, Artificial Intelligence and the Global Economy.