Money bill is exhaustively defined in the constitution but it is often interpreted with political expediency in mind rather than the purpose and intent behind carving out this exception

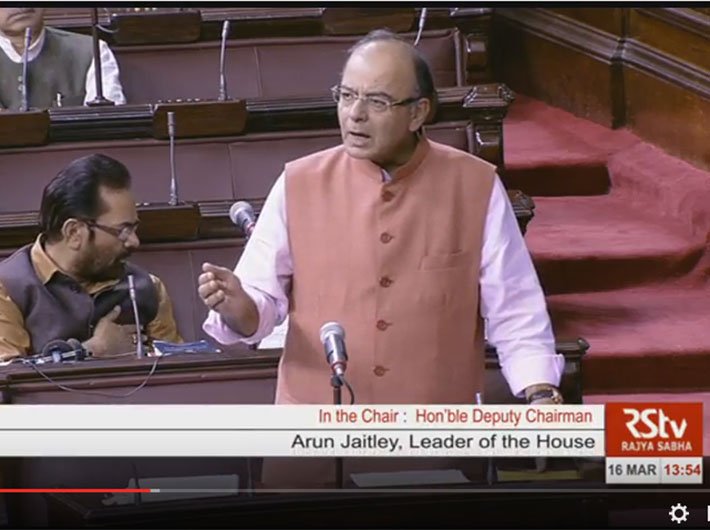

The government brought in the Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and Other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Bill, 2016, to give statutory backing to the Aadhaar scheme launched in 2009. While the scheme was already under the supreme court scanner for invading privacy, the legislative move led to another controversy. The government’s decision to classify the bill as a money bill to bypass the Rajya Sabha, where it lacks majority, may have tainted the law-making process.

Though our constitution has relegated the role of the Rajya Sabha in the law-making process only in case of certain financial matters specifically enumerated under Article 110(1), the use of the money bill route by the government to sail through with the controversial Aadhaar bill highlights the need for clear guidelines to check any misuse of the provision to bypass effective scrutiny from the Rajya Sabha.

Article 110(1) states that a bill would be deemed a money bill if it contains “only” provisions dealing with all or any of the following matters: (a) the imposition, abolition, remission, alteration or regulation of any tax; (b) the regulation of the borrowing of money or the giving of any guarantee by the government of India, or the amendment of the law with respect to any financial obligations undertaken or to be undertaken by the government of India; (c) the custody of the consolidated fund or the contingency fund of India, the payment of moneys into or the withdrawal of moneys from any such fund; (d) the appropriation of moneys out of the consolidated fund of India; (e) the declaring of any expenditure to be expenditure charged on the consolidated fund of India or the increasing of the amount of any such expenditure; (f) the receipt of money on account of the consolidated fund of India or the public account of India or the custody or issue of such money or the audit of the accounts of the union or of a state; or (g) any matter incidental to any of the matters specified in sub-clauses (a) to (f).

The Constituent Assembly debates show that the exception was carved out primarily to cut delays only in case of financial matters specifically listed in Article 110(1). In fact, an amendment by Ghanshyam Singh Gupta to delete the word “only” was rejected by the assembly.

Another member, KT Shah, who also wanted more powers for the Lok Sabha, pointed out that the struggles for supremacy between the House of Commons and the House of Lords in England almost invariably centred on the definition or scope of a money bill and the powers of the House of Lords to deal with money bills had been gradually curtailed. On the definition of the money bill in the draft constitution, he said there was “considerable room for apprehension that the powers of the House of the People over matters financial will not be as wide”.

Since the constitution came into force, the interpretation of the provision has, more often than not, been to the contrary. Notwithstanding the exhaustive list, there have been controversies over ordinary bills being classified as money bills in view of the advantages associated with it. At times the speaker decides the fate of a law, as a bill certified as money bill does not face legislative hurdles after being cleared by the Lok Sabha. The Rajya Sabha can make recommendations but cannot reject it and if it does not return the bill within 14 days, it will be deemed to have been passed. Such a bill cannot be referred to any committee and the president cannot return it for reconsideration.

Looking at the Aadhaar bill in the light of Article 110(1), there are serious doubts over a bill providing for creation of a body like the Unique Identification Authority of India, authorising collection, preservation and use of biometric data of individuals for various purposes including disclosure in the name of national security, protection of privacy, etc. being certified as a money bill merely because the preface highlights the “targeted delivery of subsidies” as one of the main objectives of the bill.

The first Lok Sabha speaker, GV Mavalankar, stressed that the word “only” was not “restrictive” and if a bill dealt with a tax, it could also have provisions necessary for administration of that tax. His interpretation needs to be seen in the light of Article 110(1)(g) which allows matters incidental to other matters in the list and not beyond that.

Taking advantage of the scope for inclusion of “incidental” matters, the government may have taken the circuitous route to law-making by withdrawing the UPA’s Aadhaar Bill – hanging fire since 2010 – and moving a fresh one classifying it as money bill. The move, however, raises questions as use of Aadhaar is not proposed to be limited to identification of beneficiaries of subsidy and the UPA version with similar provisions was not introduced as a money bill.

Undoubtedly, the constitution-makers borrowed from the practice in the UK but we have failed to learn from their experience thereafter. In fact, we relied on the UK’s Parliament Act 1911 for defining money bill. Section 1(2) of the 1911 Act also uses the term “only” while enumerating similar provisions as in Article 110(1).

Though the speaker’s certificate on money bill in the UK (as in India) is “conclusive for all purposes”, the Act mandates the speaker to “consult” two senior backbenchers, usually one from either side of the house, appointed by the committee of selection from amongst those senior MPs who chair general committees. Further, there is the office of parliamentary counsel to advise whether the speaker should certify a bill as a money bill.

Coming to the practice in the UK, Erskine May’s Parliamentary Practice, an authority on the UK’s parliamentary practice, states that “even if the main object of a bill is to create a new charge on the consolidated fund or on money provided by parliament, the bill will not be certified [as a money bill] if it is apparent that the primary purpose of the new charge is not purely financial”.

The Aadhaar bill does not seem to fit the bill. It was apparently not financial exigency (as envisaged by constitution-makers) but political expediency which may have weighed heavy when the government – which lacks majority in the Rajya Sabha – decided to classify it as a money bill.

The controversy calls for a serious debate on unbridled power enjoyed by the speaker in this regard as a money bill cannot only be used to make new laws having considerable impact on the rights of citizens but also to amend laws (originally passed as ordinary bills by both houses of parliament) without taking the Rajya Sabha into confidence. Interpreting Mavalankar’s view to make the word “only” meaningless is neither convincing nor in larger public interest. The term “incidental” should include matters linked “only” to the provisions enumerated in Article 110(1). The responsibility to ensure that the privilege is not abused is primarily on the speaker and parliament.

The supreme court in 2014 refused to interfere with the decision of the Uttar Pradesh assembly speaker certifying an amendment bill to increase the tenure of the Lokayukta as a money bill, despite the fact that the bill amended the Uttar Pradesh Lokayukta and Up-Lokayuktas Act, 1975, which was passed as an ordinary bill by both houses. The court stressed that the decision of the speaker was final and on the finality of the decision, and that the proceedings of the legislature being important legislative privilege could not be inquired into by courts. “The question whether a bill is a money bill or not can be raised only in the state legislative assembly by a member thereof when the bill is pending in the state legislature and before it becomes an Act,” the court added.

Given the fact that the court recognised the decision-making process as part of legislative privilege, the responsibility for bringing about reform is mainly on parliamentarians and legislators who are duty-bound to protect the rights of citizens. n

Singh is a Delhi-based lawyer.

(This article was published in April 1-15, 2016 edition)