Unlike sausage-making, policy-making process could be a mouthwatering treat for both its benefactors and beneficiaries when cooked and served well…

It is believed that Otto von Bismark, the first Chancellor of the German empire from 19th century, was often quoted as saying, “Laws are like sausages. It is best not to see them being made.” The idea is that one tends to lose trust and confidence in proportion to the knowledge one has of how the law was made. One wonders if the same is also true for policy and the policy-making process, an informal first cousin of the law.

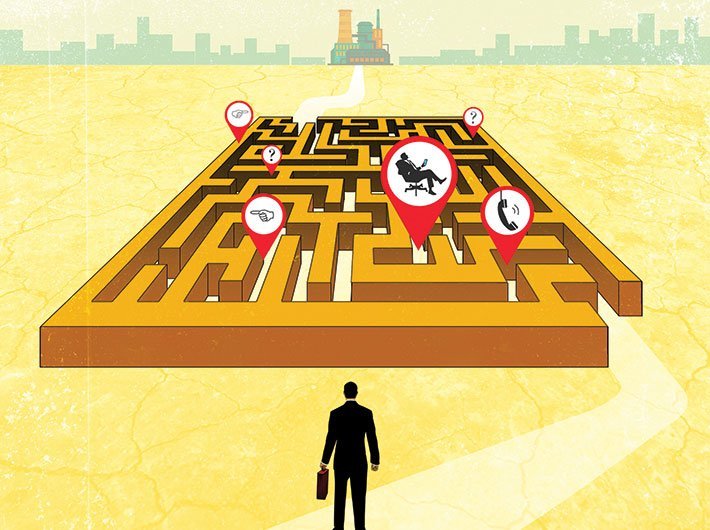

Depending on the problem it aims to address and the process that’s adopted to design a cohesive problem-solving framework, the policy-making process can be a grand, messy affair. If done well, the end result can be a charming ensemble where the variety of stakeholders (politics-bureaucracy-academia-society) perform together towards a common goal – welfare. If not, it reduces to an asynchronous medley of fractious groups singing from different hymn sheets. More often than not, there is also a temptation to rush into policy-making with ill-defined problem statements, lack of depth in data and evidence, personal agendas, partisanship and ideology and, worst of all, hasty, extempore decisions, making the given policy or law untenable and inadequate.

A rather simplistic but reliable remedy to a rushed process can be evidence-based policy-making which, as the name suggests, has evidence at its core. To take an example, globally the policy around climate change is being developed based on scientific evidence. To state the obvious, the quantum jump in atmospheric CO2, global temperature rise by 2 degrees, oceans warming by 0.33 degree Celsius since 1969, shrinking ice sheets (Greenland lost an average of 279 billion tons of ice per year between 1993 and 2019, while Antarctica lost about 148 billion tons of ice per year) are just a few data points that unequivocally conclude that climate change is real. Based on these hard facts, governments around the world are determined to make a long-term commitment to ecologically sustainable economic development via their climate change policies.

Rich, high-quality scientific research, data trends and the totality of evidence produced by credible institutions and research bodies are easily the hallmark of a good policy. Like in the case of climate change, scientifically proven data can be the bedrock of decision-making across all local and global issues ranging from education to poverty-alleviation, labour markets or healthcare.

In a more recent example of evidence-based policy changes, what (justifiably) started as a low-on-data strategy making for Covid-19 mitigation soon turned into a quick-to-adapt-to-emerging-data process. Evidence nudged government authorities to conclude that accelerating vaccination, easing restrictions, avoiding lockdowns, reopening schools and emphasising education and harm reduction approaches over absolutist approaches worked well in keeping the virus under check.

In another example, education policies globally are being designed based on evidence collected from schools. For instance, smaller class sizes lead to better student-teacher focus, use of technology enhances learning, and experiential teaching techniques lead to better comprehension.

The stark opposite of evidence is ideology or opinions. At its best, the ideology can be political in nature and, at worst, it could be guesswork, hunches, even speculations. Whatever be its form, it can play havoc and entirely derail an objective policy-drafting process. It not only affects the way evidence is received in policy circles but also the way in which it is researched, published and disseminated.

The detractors of evidence-based policy-making might argue that science can be selectively mobilised to bolster one’s own position whereas it’s the only way forward as long as the methodology to gather evidence is all encompassing and the people involved in deploying the methodology are free from biases and not predisposed to a certain ideology.

In conclusion, while the sausage-making process might not be a feast to watch but to eat, the policy and the policy-making process in contrast could be a mouthwatering treat for both its benefactors and beneficiaries when cooked and served well.

Anushree Lakshminarayanan is Director, External Affairs, IPM India.