As a development economist, he shares his thoughts on DBT, Aadhaar, and cash transfer under the National Food Security Act, 2013

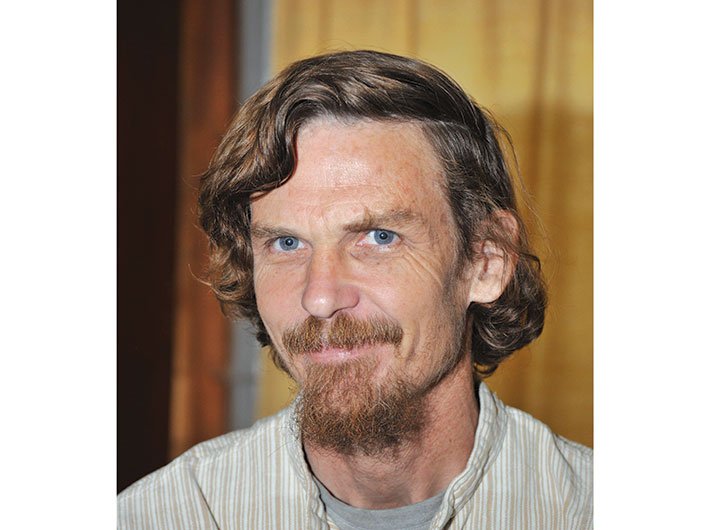

Jean Dreze is equally concerned with theory of development economics as with its practice. A visiting professor at the department of economics in Ranchi University, he has extensively worked on issues related to hunger, famine, gender inequality, child health and education. He has also been at the forefront of several social movements, including the right-to-information and right-to-food campaigns. As a member of the national advisory council (NAC) during the UPA1 government, he conceptualised and drafted the first version of NREGA. In an email interaction with Pratap Vikram Singh, he shared his thoughts on direct benefit transfer, Aadhaar, and cash transfer under the National Food Security Act, 2013. Excerpts:

What are your views on the cash transfer scheme that aims to replace supply of subsidised ration to beneficiaries?

I support some cash transfer schemes, such as social security pensions and maternity entitlements. Interestingly, the central government is undermining these schemes even as it swears by cash transfers as a substitute for the public distribution system (PDS). I am not in favour of that, at least not for the time being. The National Food Security Act is finally being implemented in most states and this is not the time to confuse matters with hasty attempts to replace the PDS with cash transfers. Most of the pilots have failed so far, confirming that there is a long way to go before cash transfers are an appropriate alternative to the PDS, especially in the poorer parts of the country.

Since India is a welfare state, should the government relinquish its responsibility of providing subsidised ration to the deprived and vulnerable?

I don’t think that India is a welfare state by any stretch of imagination. From international perspective, social spending levels in India are very low, as a proportion of GDP. The health system is almost entirely private, and there is no social security system worth the name. Some Indian states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Himachal Pradesh have relatively well developed welfare provisions. These are doing quite well. But the bulk of India is way behind. It is against this background that there is a strong case for expanding social programmes, more so because the economy is doing really well.

Coming to the PDS, it has become a very important form of social security for millions of families, especially in the poorer states. Perhaps a day will come when cash transfers can serve that purpose too, but I think that time is quite far away. So I am in favour of consolidating and improving the system, starting with effective implementation of the National Food Security Act, rather than winding it up hastily.

The government has been advocating cash transfer to ensure that beneficiaries receive their entitlement. Isn’t pilferage a matter of concern?

Beneficiaries can also receive their entitlements from the PDS. Many states have made very good progress with PDS reforms in recent years, including Chhattisgarh, Odisha and Madhya Pradesh. Other states have their work cut out. Poor families generally prefer food entitlements to cash transfers for a variety of reasons: inadequate banking facilities, fear of misuse of money, lack of faith in the government’s commitment to protecting cash transfers from inflation, and so on. It is not the poor, but the government who stands to gain from cash transfers, by saving money. That is certainly a consideration, but people’s interests come first.

How do you look at the prospects of integrating Aadhaar with welfare schemes, including MNREGS and pension?

Most of the welfare applications of Aadhaar that have been proposed so far are unnecessary and counterproductive. In Jharkhand, where I live, some of them have caused a lot of damage. For instance, there have been repeated attempts to make Aadhaar compulsory for NREGA workers, for no clear purpose. NREGA functionaries were mobilised for months on end, using very top-down methods, to “seed” the accounts of NREGA workers with Aadhaar numbers. Wage payments were often held up or even blocked because of seeding problems. Worse, job cards were cancelled en masse as a short-cut to enable NREGA functionaries to meet the seeding targets. Supreme court orders were brazenly violated on the way. Today, there is a serious danger of further damage as Aadhaar technology is sought to be imposed on the PDS in Jharkhand, again with no clear purpose.

If the government really wants to proceed with welfare applications of Aadhaar, it has a lot of homework to do. First, it should abide by the supreme court order. Second, a legal framework for Aadhaar needs to be created, with adequate safeguards against violation of privacy and other abuses. Third, hidden coercion must stop and all applications should be genuinely voluntary, as they claim to be. Fourth, the purpose of the welfare applications must be clarified. Only then will a sensible debate on these applications be possible.

The government is planning to manage all welfare schemes through a proposed social security platform – a national electronic database of beneficiaries with their Aadhaar, NPR and socio-economic caste census. Is it the right way?

We have heard of many such “plans” in the last few years. It is difficult to comment until something specific is on the table. If it is a plan to bring cash-transfer components of all welfare schemes, such as NREGA wage payments and social security pensions, into a single payments platform, it may have some merit. If it is a plan to replace welfare schemes themselves with cash transfers, I would oppose it. Cash transfers have a role, but we also need midday meals, health care, free textbooks, and many public services in kind. This is elementary economics as well as a clear lesson from development experiences around the world, or for that matter within India.

The article was published in March 15-31, 2016 issue. The interview was taken before Aadhaar bill was passed in LS.