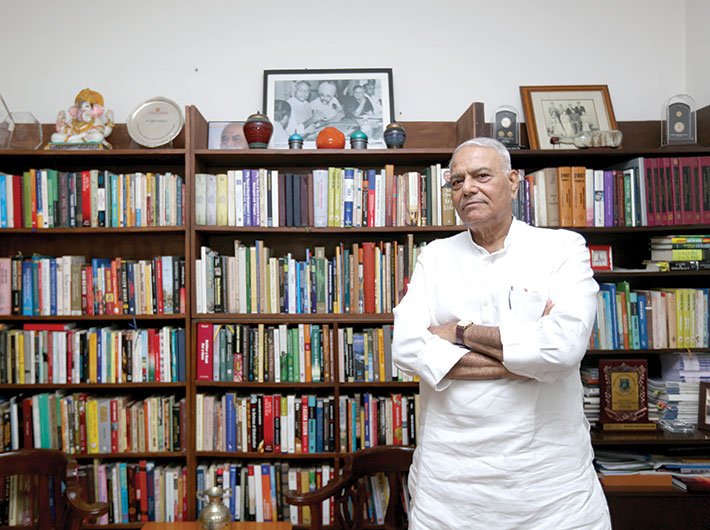

Former finance minister Yashwant Sinha, speaks on his new book, economic reforms and political opportunism

Last year the nation marked the 25th anniversary of the launch of economic liberalisation. Back in those tumultuous days, Yashwant Sinha was an important part of the dramatis personae involved in the reforms process. As finance minister in the short-lived Chandra Shekhar government, he steered the economy during a critical phase, and later, as finance minister in the NDA government, he gave the reform narrative a bipartisan support. In July, Sinha, along with co-editor Vinay K Srivastava, published a collection of essays on the reform saga, titled The Future of Indian Economy: Past Reforms and Challenges Ahead (Rupa Publications). Sinha spoke to Swati Chandra about the eclectic anthology as well as about the economy. Edited excerpts:

How was the idea of this book conceived?

It was conceived by my co-editor Vinay K Srivastava, who is an academician. I thought it was a good idea. There have been several books written on economic reforms in the last 25 years but these were by single authors. A compilation of views by different experts to cover most aspects of economic reforms was the idea behind this book. I have also contributed an essay that deals with people’s acceptance of economic reforms. I and Vinay have done an introductory essay as well. Overall, the book is a very good progress report of the 25 years of economic reforms and brings together domain knowledge from various experts.

You have written that an ‘East India Company syndrome’ is responsible for opposition to reforms.

The overall theme of my essay is the acceptability of the reforms in India. I have said that people who have opposed the reforms in the last 25 years have been generally mentioning a set of arguments and one of those arguments has been the fear of economic colonisation, which is what the East India Company did. It is easy to mislead people by saying that, ‘Look, this is what the company did; this is how India came under the British rule through commerce.’ So commerce has emerged as a tool of not only exploitation by the more powerful but it has also emerged as a tool of political mastery over a country or region.

I mentioned this to emphasise that it is easy to raise this point at an emotional level and mislead people. And at the same time, I have also said that foreign investment is not the sum total of the economic reforms. In many cases, the commitment of a government to economic reforms is generally measured with the rest of the developed world.

What are the ‘challenges ahead’ – the subtitle of the book?

They are many. The first is to make the economic reforms acceptable by the people. If we do not do that, there will be opposition by the political parties, in parliament, by the states, and more importantly, at the level of people at large.

The other point is how we define economic reforms. I define it as any step which will fuel economic growth or give impetus to economic growth. Now, there are banking reforms, which makes the life of corporates easy. There are reforms in the area of ease of doing business. There are reforms in the capital market which help investors. There are reforms in taxation. But these do not touch the lives of common citizens directly. We are sitting in a beautiful sector of Noida, but a few miles away from here, there are people living without proper infrastructure. So it is very easy to go to people living under those conditions and say, ‘economic reforms are bad and did nothing for you.’ They will be persuaded and will support parties which are anti-reforms.

One of the major governance failures in the last 70 years is that we have not been able to solve two primary issues. One is to provide livelihood, and two is to provide quality of life to the people. There are many villages which do not have roads, drinking water facility, better health and education. People who are still living under such conditions are naturally dissatisfied with the whole process of economic reforms and they turn against it. So, the prescription should be that along with taking steps that fuel growth, the government must take steps which will directly impact the lives of the people. I have been emphasising on identifying the basic needs of the people. This debate on basic needs has been on since the 1930s, when the Congress constituted a committee under Nehru to decide what the basic needs were and decide a plan to meet the needs of the people. There were several plans after plans and we have now reached a stage where the planning commission has been abolished, but the basic needs of people are still not met. We have achieved a very high growth rate, but has the market directly contributed to the welfare of the people? No. This responsibility of livelihood provision and quality of life improvement steps should be the direct responsibility of the centre and the states.

At the book launch, you said that most parties are opportunistic when it comes to reforms. Is it the case with GST and Aadhaar?

Yes, definitely. The two major political parties, the BJP and the Congress, have been changing their stands depending upon whether they are in the government or in the opposition. There are parties who have an ideological opposition to reforms. We have ideological differences with them and that is understood. But with major political parties, it is not ideological but political.

The insurance sector reform is a very good example of this. When Chidambaram was the finance minister in 1996-98, he brought a bill on the insurance sector. Within his own coalition, there were parties which opposed it. We were for internal liberalisation of the insurance sector but not for foreign direct investment. When he moved the bill, the socialists and the communists opposed it in parliament and the bill was withdrawn. Soon after, when I became FM and consulted experts, I found that the internal liberalisation position was not valid. Because we needed huge investment and Rs 100 crore should have been the minimum equity of the company. There were very few companies which were in a position to invest this much. Then I was convinced that we needed foreign investment. So I prepared a bill and took it to the cabinet and it was finally introduced in parliament. That bill had a provision for 49 percent foreign investment and 51 percent Indian investment and the rest of the provisions were built on this basis. It was the Congress then that started opposing the bill saying that we will not allow foreign investment more than 26 percent. We did not have majority in the Rajya Sabha and thus we had to make compromises. This was one compromise that NDA made and we decided on 26 percent foreign investment. This is how the bill was passed. But just four years down the line, when UPA-I came to power, Chidambaram got enlightenment like Gautam Buddha and they brought a bill in parliament proposing that foreign investment should be capped at 49 percent. The bill remained stalled and even saw the 2008 recession period. We gave a report stating that we don’t approve the idea of raising foreign investment to 49 percent. Whenever I was consulted, I used to give views on what could have been done. However, the BJP leadership at that time did not even accept my formula and the bill remained pending. When we came to power in 2014, we were in such a hurry that we did this through an ordinance. So where was the commitment of the BJP when we were in the opposition?

Coming to the GST, it was supported by the BJP in the party manifesto in 2009 but two states ruled by BJP were not in favour of it. We have also passed the Aadhaar bill as a money bill. So, views change depending on whether you are in the government or in the opposition. This is the pattern of the Indian politics.

Is there any advantage in making Aadhaar a super ID?

There are many problems in the Aadhaar. I will mention a few. In NDA, we came up with an idea of citizens’ identity card and later the need for National Population Register was realised after the Census of 2001. The UPA-II started Aadhaar without a law; so, many people challenged it. They brought a bill and it was so defective that the committee on finance rejected it. Second, you can’t proceed on two tracks. There was NPR as well as Aadhaar, meaning 50 percent of the population was to be covered under NPR and another 50 percent was to be covered under Aadhaar. Meanwhile, even Chidambaram as home minister had raised doubts on the data collection and protection issues. Thirdly, it was already in public domain through media reports that it was being misused. It was mentioned that it will be available to all residents, not citizens, (that would also include) illegal immigrants. Nobody talks about NPR anymore. It is Aadhaar all the way now. It has a legislative sanction and is being made compulsory. I myself could not link PAN with Aadhaar as my name on the PAN was Yashwant Sinha and on the Aadhaar it was Shri Yashwant Sinha. Later I got a new Aadhaar card made – this too happened with a lot of difficulties as the scanner was not able to read my fingerprints. What I am saying is that with biometric details there are problems. A labourer who works with his hands has his fingerprints blurred. So it is not a 100 percent proof of identity throughout life. There are serious privacy issues and one does not know whether it will succeed or not.

Is the process of reforms in India slow?

The process of reforms has been very slow, unlike in China – especially, the economic reforms which require legislative changes and states’ consensus. The results have also been slow. Therefore in 25 years we have not been able to reach where other countries have reached [in the same period].

If you were part of the government, which reforms would you have prioritised?

We have not been able to do anything on FDI in retail, labour reforms, privatisation of PSUs, PSU banks, the whole area of subsidies, open markets, a common market for agriculture, other agricultural reforms, and land acquisition.

Then there are issues which are larger than economic reforms: say, administrative reforms. Do we have the administrative structure and machinery to support the economic reforms process? No. We are trying to do that through the old creaky machinery that we inherited from the British. Then comes the need for judicial reforms. There have been instances of judicial interference in economic reforms. At the drop of a hat one can go to the court and get a stay order. There are many heads where we have not made any progress and these should be the subject for future reforms.

What do you think of the bank NPA problem? Is the government working in the right direction to deal with it?

It is largely the outcome of the administrative and policy paralysis of the UPA government. As a result, a very large number of projects were stalled in various sectors, be mining, power or road, and where NPAs have accumulated. When I was the spokesperson of the BJP on economic issues until 2014, people would ask me what you will do if you come to power and my standard reply was the first thing that we would do is to get rid of the policy and administrative paralysis and take policy steps to clear the backlog of stalled projects so that we could move faster. However, in the last three years, a lot of progress has been made but it has not been sufficient to clear the NPA problem. I recently saw a report stating that the bank credit growth has hit a 20-year low. There is no money in banks. The NPA problem should have been resolved much, much earlier. When I was the finance minister during 1990-91, it was a much bigger problem. We took a number of steps. The most important step that we need to take is to improve the economy: if economy picks up then the NPA problem will be generally taken care of. If economy remains in a slow mode then it is difficult. Now, we are growing at over 7 percent. Obviously it’s not sufficient, we need to grow faster. So the stalled projects and the NPA problem are still major problems in the economy.

(The interview appears in the August 1-15, 2017 issue of Governance Now)