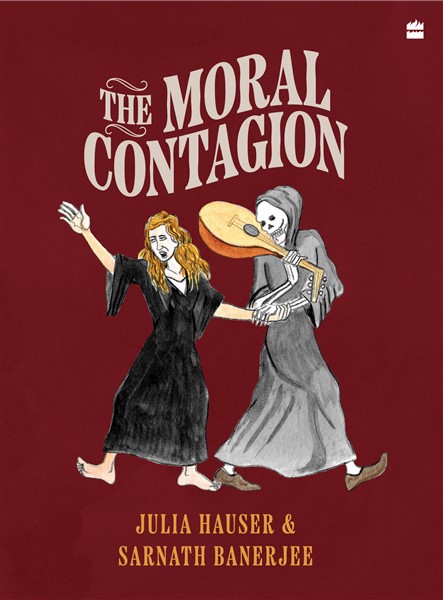

Melding meticulous research with imaginative storytelling, ‘Moral Contagion’ also reflects on how societies and individuals tend to react when faced with that existential threat

The Moral Contagion

By Julia Hauser and Sarnath Banerjee

HarperCollins, 140 pages, Rs 699

The world has largely come out of an especially challenging phase of the Covid-19 pandemic. New strains keep making news, but people are scared less and less. The world is back to what is called normal, even if, during those days of lockdowns and ever-rising mortality charts, it seemed it would never be the same again. Since antiquity, the world has seen innumerable episodes of this nature, and has also seen people who thought each of them was special to their generation.

The world has largely come out of an especially challenging phase of the Covid-19 pandemic. New strains keep making news, but people are scared less and less. The world is back to what is called normal, even if, during those days of lockdowns and ever-rising mortality charts, it seemed it would never be the same again. Since antiquity, the world has seen innumerable episodes of this nature, and has also seen people who thought each of them was special to their generation.

In the process, however, our knowledge about them – the plagues and pandemics, their causes and their containment, has increased incrementally. ‘The Moral Contagion’ makes much of it accessible for non-specialist readers who would like to delve deeper into the history of the weird experience we all had for a couple of years since the coronavirus breakout.

You remember waking up shivering and with a sore throat. “Is it Covid?” You took a test and waited for the result. Luckily all was well. Or was not – and then began a nightmarish scenario, that became painfully familiar to all of us. India was one of the countries hit hardest by the Covid-19 pandemic, with a tragically high number of casualties. The pandemic also made some things an integral part of our lives: wearing masks, sanitizing, social distancing, isolating oneself.

None of this, however, is unique—even though the Covid virus was a new one. Over the centuries, wave after wave of the devastating plague pandemic had impacted humanity in similar ways, and the responses to the threats it posed had been similar too. From sixth-century Constantinople and fourteenth-century Europe to Islamic Spain, seventeenth-century London, eighteenth-century Aleppo, and Hong Kong, Bombay, San Francisco and South Africa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the history of the plague is, in a way, the story of modern civilization.

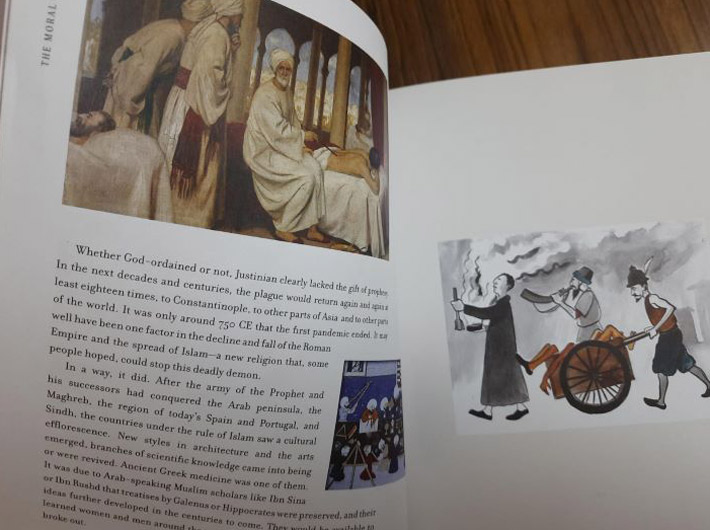

‘The Moral Contagion’ is an insightful and absorbing take on that story. Based on Julia Hauser’s rigorous scholarship and enhanced by Sarnath Banerjee’s wry illustrations, this utterly gripping book playfully melds meticulous research with imaginative storytelling to create a graphic narrative about pandemics and reflect on how societies and individuals tend to react when faced with an adversary that is, literally, larger than life.

Based on Hauser’s rigorous scholarship and enhanced by Sarnath Banerjee’s wry illustrations, this utterly gripping book playfully melds meticulous research with imaginative storytelling to create a graphic narrative about pandemics from sixth-century Constantinople to late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and how it affected human relationships, systems of belief, knowledge and political power.

Julia Hauser is a senior lecturer in Modern History at the University of Kassel, Germany, and an alumna of the Arab–German Young Academy of Sciences and Humanities (AGYA). Hauser was a fellow at the Orient Institut Beirut, Rice University, Houston/Texas, the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences Calcutta, and ICAS:MP, Delhi. Among her publications is ‘A Taste for Purity: An Entangled History of Vegetarianism” (New York: Columbia University Press, 2023).

Sarnath Banerjee is among the pioneers of graphic fiction in India, beginning with the cult-classic ‘Corridor’ (Penguin, 2004), followed by ‘The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers’ (Penguin, 2007), ‘The Harappa Files’ (HarperCollins, 2011), ‘All Quiet in Vikaspuri’ (HarperCollins, 2015) and ‘Doab Dil’ (Penguin, 2019).

In collaboration with historians, Banerjee had produced ‘Liquid History of Vasco Da Gama’ for the Kochi Biennial 2014, and ‘The Poona Circle’, a series of vandalized history textbooks, for the Pune Biennale 2017. He has been a fellow of the Akademie Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart; Indian Foundation for the Arts, Bangalore; and MacArthur Foundation. He received the Belknap fellowship, Princeton, and the CAST fellowship, MIT, in 2019.

Hauser said in a statement, “The idea for ‘The Moral Contagion’ came to us in the early phase of the Covid-19 pandemic when the fear of this unknown virus and the pain of being separated from one’s wider social circle were dominant in many people’s lives. Yet others, generally members of ethnic minorities, found themselves scapegoated for allegedly spreading the virus. As we discussed these aspects, I mentioned that some of these social dynamics had been at work much earlier, most notably during the plague.

“Sarnath was intrigued by this, and this is how the book came into being. The Moral Contagion tells the story of the plague from antiquity to the early twentieth century in different cities and different parts of the world, from sixth-century Constantinople to late 19-century Bombay. The book examines how societies, and indeed how morality, changed due to the plague. Since India was hit particularly hard by the Covid-19 pandemic, we hope that ‘The Moral Contagion’ will be of interest to many readers.”

Banerjee added, “One of the big satisfaction[s] of doing this book was to comb through the visual culture and historical references around the great plagues in preparation for the drawings. The drawings allowed me to meander freely through the centuries, getting to understand the moral universe of the times and feeling as if I was living through them.

“Julia's sparkling storytelling style allowed the drawings to be interpretive rather than illustrative. I was given the freedom to build a parallel visual narrative that went alongside the main story. One of the great advantages of drawing is that it lets you slow down. While drawing Byzantine architecture, opium dens of colonial Hong Kong, Plague hospitals in Bombay, interiors of Damascus houses, it felt as if time stopped and went backward.

“Academics have great insights and imagination. Sadly, their works are often trapped in institutions and circulated between peers. They rarely ever affect culture and when they do it is always a significant step in influencing civil society.”