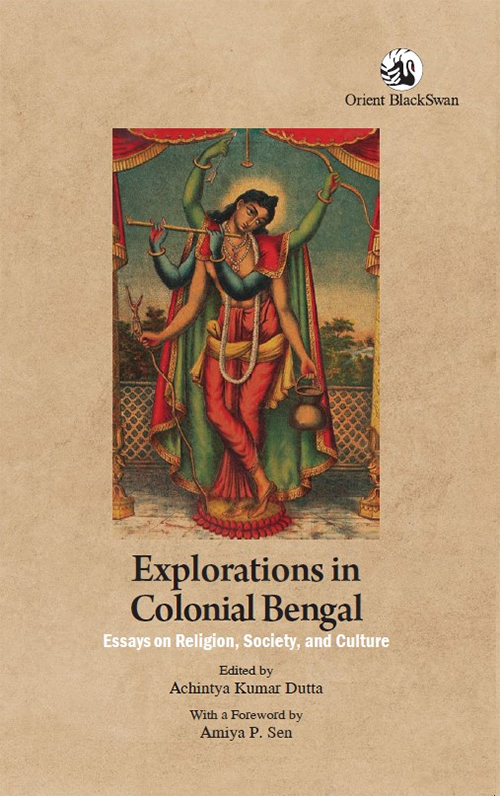

An excerpt from Anuradha Roy’s essay on the seminal text, from the anthology ‘Explorations in Colonial Bengal’, edited by Achintya Kumar Dutta

Explorations in Colonial Bengal: Essays on Religion, Society, and Culture

Edited by Achintya Kumar Dutta, with a Foreword by Amiya P. Sen

Orient BlackSwan, 384 pages, Rs. 1495.00

Bengal was the primary centre of East-West interaction and the first region in India to be influenced by and resonate with British culture during colonial times. ‘Explorations in Colonial Bengal’ sheds light on some important, yet relatively less-explored aspects of sociocultural changes that took place in Bengal in the colonial milieu. The essays engage with two major themes: Vaishnavism, and the society and culture of nineteenth and twentieth-century Bengal. The contributing authors show how Vaishnavism attracted the attention of multiple ethnic communities and institutions in contemporary society. They also study relatively unknown aspects of this culture, such as the role of women in the evolution of Bengali Vaishnava traditions. The second section addresses the society, economy, and politics of colonial Bengal and explores subjects as diverse as the close connection between history and literature; Tagore’s concepts of nationalism and his liberal humanism; the central political and ritual place assigned to water in its various forms in social relations; and Bengal’s economy and its nascent banking system during the early days of the East India Company.

Bengal was the primary centre of East-West interaction and the first region in India to be influenced by and resonate with British culture during colonial times. ‘Explorations in Colonial Bengal’ sheds light on some important, yet relatively less-explored aspects of sociocultural changes that took place in Bengal in the colonial milieu. The essays engage with two major themes: Vaishnavism, and the society and culture of nineteenth and twentieth-century Bengal. The contributing authors show how Vaishnavism attracted the attention of multiple ethnic communities and institutions in contemporary society. They also study relatively unknown aspects of this culture, such as the role of women in the evolution of Bengali Vaishnava traditions. The second section addresses the society, economy, and politics of colonial Bengal and explores subjects as diverse as the close connection between history and literature; Tagore’s concepts of nationalism and his liberal humanism; the central political and ritual place assigned to water in its various forms in social relations; and Bengal’s economy and its nascent banking system during the early days of the East India Company.

The editor, Achintya Kumar Dutta, is professor of history at The University of Burdwan, West Bengal.

Here is an excerpt from an essay from this book:

Rejection of Nationalism and Much More

Reading Tagore’s Nationalism 100 Years On

By Anuradha Roy

Rabindranath Tagore’s book ‘Nationalism’ (2007 [1917]), where he completely rejected the ideology of nationalism, is often cited these days to counter the highly authoritarian and coercive variety of nationalism that we can see all around us. This is a nationalism that is seeking to recast Indian national identity along a religious majoritarian and monocultural line. Rereading the book a century after its writing, however, I realised that its value consists of much more than its bold rejection of nationalism. It raises certain questions regarding society and civilisation which are worth heeding today, regardless of the attempt by any particular variety of nationalism, or any ideology for that matter, to aggressively dominate the people. Indeed, the ideas that informed his critique of nationalism in this book were to develop further and constitute a constructive proposal for a kind of humanistic civil religion in a later book, ‘The Religion of Man’ (2005 [1930]), where he moved beyond the question of nationalism in his quest for justice and peace in human order, and also for the complete self-realisation of individual human beings.

This chapter is divided into three parts. The first part, ‘Prelude to the Book Nationalism’, will show how Tagore, who had been deeply involved in the national movement of his country right from his childhood, eventually turned against nationalism. In the second part, ‘Reading Nationalism’, we will read the book itself to see what Tagore says here that goes beyond his condemnation of nationalism while being related to it; how he raises some very fundamental questions regarding society, civilisation, and more importantly, human nature, in this book, with rare insight and wisdom. While the book’s rejection of nationalism is indeed important, its engagement with these questions seems to me to be even more profound, and hence more significant. And I think this should place Tagore on the same pedestal as some of the greatest thinkers of the world. In the third part, I will point out the limitations of some of Tagore’s views expressed in the book and attempt an overall assessment.

Prelude to the book ‘Nationalism’

These days, Tagore is often hailed (or scorned) for his ‘anti-nationalism’. But we must remember that he did take quite some time to develop this anti-nationalistic stand. Anyway, whether Tagore was ever a nationalist or not seems to me to be a moot question. More importantly, Tagore’s nationalism, had any such thing at all existed, was based on some fundamental human values, which are important even if we take them away from their nationalist moorings. And it is these values that ultimately pushed him away from nationalism and these same values were given exposition in Nationalism, making it much more than an ‘anti-national’ exhortation.

Apparently, Tagore was very much a part of the Indian national movement and any cultural history of this movement cannot but feature him prominently. His love for and reflections on his country evidently germinated in the context of the emergent nationalist movement in the second half of the nineteenth century, particularly because his own family was deeply involved in it. As this movement continued to expand its agenda, adjusting its current programme and future goals, he not only kept pace, but also voiced its most forward and progressive thoughts. Thus, he represented Indian nationalism at its best. And then came a time when he went beyond that, thanks to the remarkable originality of his mind. It is well-known that in the post-Swadeshi years, his relationship with the mainstream nationalist movement of India altered decisively and permanently, culminating in his global and complete denunciation of nationalism itself in the book Nationalism. But even after this, he continued to lend support to whatever humane, dynamic, freedom-loving, and courageous elements he found in different streams of the Indian nationalist movement (Roy 2017).

So long as and so far as the nation was a symbol of wider selfhood to him, a symbol of mutuality and living together that is innate to human nature, Tagore lent his support to the nationalist ideology. But his faith in nationalism appeared shaky from at least the late nineteenth century. Even in his Swadeshi days in the first decade of the twentieth century, that is, his most intense nationalist phase, Tagore expressed clear reservations about nationalism. Actually, he had problems with certain modules of nationalism that he saw at home and abroad, because he found them too selfish, aggressive, and coercive. Another problem for him was the close association between the State and the nation; he had a deep-seated distrust of the mechanical and authoritarian character of the State. But had Tagore known that he had the liberty to fashion his own nation rather than cling to any particular modular form, that is, had he thought of nationalism in terms of imagination and creativity—as we do today, thanks to Benedict Anderson’s seminal book (Anderson 1983)—and had he been able to dissociate the nation from the State, he would not perhaps have been so impatient with nationalism. Indeed, as Partha Chatterjee has perceptively said, Tagore’s swadesh (one’s own country), a word that occurred frequently in his writings, was not very different from what we know as the nation today (Chatterjee 2005). Tagore had started thinking of the country in terms of imagination and creativity since his Swadeshi days. Much later, he wrote in an essay included in the book 'Kalantar' (Transition of Age):

“In 1905 I called on the Bengalis to tell them this—create your country inwardly with the help of atmashakti (self-prowess), because it is through creation that the truth is realized. Viswakarma finds himself in his own creation. To find one’s country means to feel one’s own soul on a broader basis. When we create our country with our own thoughts, deeds and love, we truly see our own soul in our country. Man’s country is the creation of man’s mind.” (Rabindra Rachanabali 1970, 24)

[Excerpt reproduced with the permission of the publishers.]