The land of abundance is engulfed in sinister, white fumes of smack and heroin

Yogesh Rajput | April 28, 2015 | Punjab

The land of five rivers has enough water; its golden fields run as far as the eye can see; prosperity is writ large over the state, yet there is a pall of sinister, white smoke over its horizon.

Punjab possibly has everything a state can ask for, maybe too much. For a majority of its youth is getting wasted from rampant drug abuse. They are the future of Punjab but their present is mired in smack and heroin.

Not only is the youth fast turning irrelevant in terms of Punjab’s progress, signs of a greater worry reflect in the state’s weakened backbone – the gradual demise of countless youngsters from drug overdose. This grim reality has created an unfortunate irony – the state has everything, yet nothing.

In a remote village of Tarn Taran district, close to the Pakistan border, lives a 60-year-old woman who has a farm for livelihood, food to eat, water to drink and a decent home to sleep. Yet, each morning she wakes up with an emptiness in her heart. It has been over a year since her son died due to drug intake. But every now and then she gets teary-eyed, and every time she takes out a worn photograph from a men’s wallet in her shirt pocket, looks at it, wipes her tears, sighs and gets back to her work.

READ: In Punjab, 16,701 drug peddlers, and counting

Amarjeet Kaur’s son Balwinder Singh used to consume smack. Though Balwinder was far from being a hardened addict, he ended his life by injecting a lethal dose in a bid to get an instant high. Balwinder was 31 years old. His family members remained in denial for long. They are still unable to grasp the reason behind his sudden death. What pinches them is that Balwinder was an amateur addict struck down by ill fate. “My son was a hardworking farmer. He never sold off any property or household valuables to buy drugs, nor did he commit any crime.

Amarjeet Kaur’s son Balwinder Singh used to consume smack. Though Balwinder was far from being a hardened addict, he ended his life by injecting a lethal dose in a bid to get an instant high. Balwinder was 31 years old. His family members remained in denial for long. They are still unable to grasp the reason behind his sudden death. What pinches them is that Balwinder was an amateur addict struck down by ill fate. “My son was a hardworking farmer. He never sold off any property or household valuables to buy drugs, nor did he commit any crime.

He was a good son, but destiny got the better of him,” says Amarjeet, her right hand shaking while clutching at her son’s picture.

Balwinder is survived by his wife and two children – an eight-year-old son and a 10-year-old daughter. She agrees to be photographed, but Amarjeet does not smile for the camera.

In the same village lives 65-year-old Jasbir Kaur. Her son, too, takes smack, like every third youngster in the area. But unlike Amarjeet, Jasbir has no kind words for her son. Every time, Maninder, the son, comes home after his daily dose, he tries to delude her into believing that he didn’t.

Maninder forgets that Jasbir is his mother. That she can read her son, no matter how old he is; like a book, even if she is illiterate.

De-addiction and beyond

“Whenever I ask him if he has taken drugs, he lies. He would even say he has never touched any such substance. But I am his mother. I can see the truth in his eyes,” says Jasbir. With Maninder spending on drugs whatever little he earns working as a part-time labourer, his wife Santosh remains in a constant state of worry. She worries about the future of their four young children. She worries about where the next meal will come from. She worries about what will happen to her after Maninder. Santosh and her mother-in-law are forced to seek labour. Slapping her forehead, Jasbir sits cursing on a small platform outside her mudhouse. “Bedagark kar rakha hai nashe ne is gaon ka (Drugs have ruined this village),” she says.

This phrase echoes all over Punjab.

Closer to Chandigarh and about 25 km from Tarn Taran, is Maqboolpura in Amritsar district. It has become internationally infamous as the ‘village of widows’. The plight of the women left behind after most of its young men succumbed to drug abuse has been highlighted by national and international media. During the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, a horde of electronic media descended upon the locality, which, in turn, made villagers here fiercely hostile towards outsiders. There have been frequent incidents of cameras being smashed and reporters manhandled. Ask anything of those working in the area, they want “nothing to do” with a story on drugs.

In another village of Tarn Taran, 25 young men died of drug overdose last year. Even as the villagers’ accounts of deaths differ with that of sarpanch Kalwant Singh (he only speaks of five such deaths), the village of 4,000 has not seen a single post-mortem after any of the drug-related deaths. “No one seeks a post-mortem,” says Sukhdev Singh, a social worker who organises anti-drug awareness campaigns in the district. And that is the reason there is no clarity on how many deaths are caused due to blood infection (Punjab has a high incidence of HIV/AIDS infection, mostly caused by multiple use of syringes used to infuse drugs).

The sarpanch says he tries his best to sensitise youth about the ill effects of drug abuse, but the “headache” just doesn’t go away. Since the only work to be found in the village is either farming or labour, addicts have started adopting unscrupulous ways to fulfil their needs. “Addicts need nearly '200-500 for drugs every day. Since they cannot earn so much money from labour work alone, they resort to stealing and robbing, in and around the village,” says Sukhdev.

“Just like a man works for food, addicts here work for drugs,” says Kalwant with a sigh.

In early mornings and late evenings, 10-12 addicts in the village walk down to their adda – a ruin of what must have been a barn – in the middle of a farm. On one of the three remaining walls, Lord Shiva sits meditating. A simple line drawing in charcoal black depicts him in almost after-drug comatose calm. One of the addicts is carrying the heroin. On the way out of his house, he mixes it with water, lifted off an open drain. The solution is then filled in an injection. By the time everybody settles, the drug is ready for use. Addicts keep passing the syringe among themselves. After taking quick shots of the drug, some of them settle in separate nooks while others remain in the huddle, before all pass out. They will remain in this position for two to four hours. Lord Shiva adds a mystic backdrop to the setting.

READ: Let’s clear some misunderstandings

The catalysts

The story remains the same for most of them. It starts with a casual try with friends, till it develops into an addiction so strong that all personal valuables are sold off. Realisation strikes when nothing is left. For some, it doesn’t come at all.

Seven years ago, Gurpreet Singh, then 16-year-old, tried his first cigarette. A curious Gurpreet just wanted to experience the kick of smoking.

“I didn’t realise when the cigarette turned into smack,” says Gurpreet. But as he started drowning in depression, he realised he needed to do something about it. The first step Gurpreet took was to stay away from “bad company”, his friends who had become hardened drug addicts. Gurpreet then checked into a drug de-addiction centre in Amritsar. He proudly says that he has not met or talked to his “friends” with whom he used to take smack daily, for the past five days.

Shashi Sharma, a whistle-blower, knows the psyche of a newbie. Sharma, who has lost close friends to drugs, says, “Many a times, youngsters think that consuming drugs once or twice would not make any difference to their health or lead to addiction. But they realise their mistake only too late. By the time they do, they have turned into addicts.”

Former Punjab DGP (prisons) writes on the politician-drug peddler nexus

For Daljeet Singh, a resident of Tarn Taran, the realisation came too late. Taking heroin for the past five years, Daljeet sold off his showroom of readymade garments to feed his habit. But that was not the end. As the money from the sale started depleting, Daljeet sold off the remaining two shops one after the other, followed by a plot of land and household items. Raising his two small children – a three-year-old daughter and a one-year-old son – Daljeet was broke. “I could not even pay the school fee,” says Daljeet. Now reduced to picture of gloom – hollow eyes set in big dark circles, sunken cheeks, slouching shoulders and wiry limbs – Daljeet must have been a strapping youth just five years ago. Sitting on his haunches at Swami Vivekananda drug de-addiction centre in Amritsar, he pulls his ears childlike while swearing upon Guru Nanak’s name to reform, for the sake of his children.

But the well-heeled are not the only ones to fall for the high. Poverty and illiteracy also drive the youth of Punjab towards drug addiction, though the consequences in such cases are borne more by family members than the addict himself. “Many addicts get married and have children without realising the extent of responsibility that follows. When the addict becomes completely unemployed or loses his life, his wife and children are forced to bear the burden of poverty,” says Sawinder Singh, councillor in Kot Khalsa. Before Balwinder died in Tarn Taran from heroin injection, his wife had once been so fed up that she went to stay at her mother’s place. She agreed to return home, a month later, only after Balwinder made several pleas.

Dr Davinder Singh, associate professor at Guru Nanak Dev University, says people often try drugs as an adventure. “They keep hearing that drugs have a relaxing effect on the mind. But they want to see for themselves its effect on the human body.” Ramandeep Singh was one such curious farmer in Amritsar. A friend had told him heroin is a great aphrodisiac. Ramandeep started injecting himself with heroin. “In the beginning, my performance in bed improved substantially. But as soon as I took a break from heroin, my performance dropped drastically. So I increased the dosage. This continued for two months. I was almost caught in the vicious cycle,” says Ramandeep. He decided to stop when he started suffering from chest and nasal congestion.

Not everybody is able to kick the habit so soon. More so schoolchildren. Most of them start with smoking cigarettes and soon take to drugs.

Their immature minds and undeveloped bodies take heavy toll. Dr Davinder Singh recalls the case of a 13-year-old who developed the habit and was later counselled. The boy was from Jalandhar, while his father used to work in Chandigarh. Once he was visiting his father, who asked his driver to take him around the city. The driver offered the boy opium. Soon their little secret made him crave for more. Once he returned to Jalandhar, he started looking for the drug. Surely, he found an unscrupulous seller too. “The boy was an all-rounder, good in studies and sports. When he came to me, he was fed up of being an addict, as he admitted to losing all his talent due to drugs,” says Dr Davinder Singh.

Kalwant Singh, the sarpanch from Tarn Taran, is aware of the rampant drug abuse among youngsters in his village. But what despairs him more is the usage of drugs by schoolchildren. “They start taking drugs as early as 12-13 years. Their growth stops. While some lucky ones are able to kick the habit, others die early of drug abuse.”

The abuse, however, is not limited to villages. In cities too, children are being lured into drugs by peddlers and addicts.

The foreign dream

Yet, it is also the attitude of youngsters in Punjab that pushes them towards drugs. Romanticising “dope-shope” in movies and songs, blindly aping the western culture and the ‘great American dream’ too are to be blamed for the increasing incidence of drugs among Punjab youth.

Former Punjab DGP (prisons) Shashi Kant explains it in the context of the period of terrorism in the state, between the early 1980s and mid 1990s. He says people in those days usually stayed in their homes due to safety concerns. “By the time terrorism ended, youngsters had become habitual of not working at all. This was mainly because land prices in Punjab had started booming and the youth did not find any reason to seek work, as they could easily live off the earnings from their land.”

The influence of western culture, in the form of movies and Punjabi song videos portraying a hedonistic lifestyle, have left the youth awestruck. Drugs make you “cool” and “happening”. “Everyone wants to become a star overnight,” says Sukhdev, the social worker from Tarn Taran.

Dr Sandeep Bhola has been heading the Kapurthala de-addiction centre since 2007. In a span of almost eight years, he has interacted with hundreds of addicts visiting the centre for treatment. In most of the cases, Dr Bhola finds a common thread – “a majority of them are misguided”. “No less than 75 percent of the youth in Punjab seek to go abroad, no matter whatever job they have to do there. This desire arises from a sense of comparison that creeps into their minds, after they see or hear about how the lives of their neighbours or friends staying in Canada or the US have changed. They apply for a US or Canada visa and wait. In the meantime, they remain indolent, only visiting the travel agent’s office by way of work. If the youngster belongs to a well-to-do family or is a landlord’s son, he would loiter around with his friends, but not study or start working till he settles abroad. From my experience, I have found that youth here is not running after white-collar jobs. They are only running after visas,” says Dr Bhola.

Deepak Babbar, executive director of Amritsar-based NGO Mission Aagaaz, says it is also the elitist approach towards life that is ruining the lives of youngsters. “People here do not have the will to work. When those coming from Bihar and UP can travel to distant places and do menial jobs, then why can’t youngsters of Punjab sweat a little?” he asks rhetorically.

For the past three years, 22-year-old Baljeet Singh has been taking a gram of heroin every day. With little interest in studies, Baljeet dropped out of school after Class 11 and joined his friends for drugs. “The usual rate of heroin is around '3,000 per gram but I had become friends with a drug dealer who used to give me the same for '1,500. In return, I used to lend him my car for a ride,” says Baljeet. Initially, Baljeet’s parents remained in the dark and chose not to believe the truth, even when they were informed by their neighbours about Baljeet’s habits. It was only when Baljeet started using syringes last year that his parents noticed injection marks on his arms. “Upon reaching home, my eyes used to be blood red and face coal black,” says Baljeet. His parents woke up to his addiction only after he sold off his gold ornaments worth '2 lakh to buy drugs. As Baljeet’s health started deteriorating, he got admitted to the Kapurthala de-addiction centre. Still in the phase of coming to terms with the damage inflicted on him by drugs, Baljeet says he cannot even remember the series of events and what all he did in the last one year.

Dr Bhola’s analysis comes alive, when one asks Baljeet his plans for future once he is reformed. “After I get well, I would go abroad,” he says.

The burden of stigma, no family support

The side effects of drug addiction are not limited to risking one’s physical and mental health. An addict also comes to be treated as a pariah by society. With the road to recovery already full of rough patches, the social stigma makes matters worse for addicts. Dealing with apprehensions while reaching out for detoxification and counselling services becomes all the more difficult for them.

Academicians and experts say a sure shot way to win half the battle is to treat drug addiction as a disease, and not as social evil. Dr Shyam Sunder Deepti, who teaches in the department of community medicine at the Government Medical College, Amritsar, is well aware of the prevalence of the stigma. Also serving as a member of the counselling board at the city’s government-run Swami Vivekananda drug de-addiction centre, Dr Deepti says he has often noticed patients (addicts in drug de-addiction centres) come from far-off places even when there are de-addiction centres in their own areas. “Many addicts feel embarrassed that their neighbours or acquaintances would get to know about their condition if they are admitted to a de-addiction centre of their hometown. To escape humiliation, many seek help from centres in other cities,” says Dr Deepti.

But facing heat from society is not the only reason that pulls addicts away from de-addiction centres. What aggravates the situation is family members turning away from the addicts. Having counselled a number of teenagers being lured into drugs, Dr Davinder knows when a boy is unable to gain attention of his family members in times of distress he is bound to reach out to his friends, who often give wrong advice.

“When parents do not attend to their children and counsel them on their day-to-day problems, children tend to seek solace among friends.

This is usually the starting point of addiction, as the child is pacified by his friends and then offered drugs to relax,” says Dr Davinder.

Family support is required not only to prevent a youngster from consuming drugs, but also after an addict receives de-addiction treatment.

Dr Deepti says many patients go back to drugs after they are discharged from a de-addiction centre in the absence of family support. “The role of a de-addiction centre in helping patients quit drugs is only 10 percent. The rest of the effort has to be made by his family members.”

Dr Deepti recalls a case where a patient came back to the Swami Vivekananda drug de-addiction centre soon after he was treated. The patient, who habitually took 40 capsules (of a prescription drug) every day, returned home after being treated at the centre. He had apparently stopped taking drugs, but his family thought otherwise. Whenever the patient came home after being out for a while, he was made to wait at the gate for a few minutes. His suspecting parents would then try to find signs of drug abuse. The patient failed to convince his parents that he had quit drugs. This uncomfortable routine continued for a few days, until he got so frustrated and angry at his family’s sceptical behaviour that he went out and consumed 40 capsules. Upon reaching home, he told his parents that he had indeed consumed drugs that day, and not on the previous occasions when he was constantly being accused of having done so.

“In many cases, parents do not have a helping attitude, instead they are discouraging. Thus, counselling of both addicts and their parents is important. I often tell patients at the de-addiction centre to chat with fellow patients and stay in touch after their treatment is over. This way they can form self-help groups to stay away from drugs,” says Dr Deepti.

Dr Bhola says public needs to be sensitised on the drug abuse issue to change the mindset of society. “If an alcoholic is found lying on the road in an unconscious state, he is not seen in such a bad light as a drug addict.”

The intricate nexus

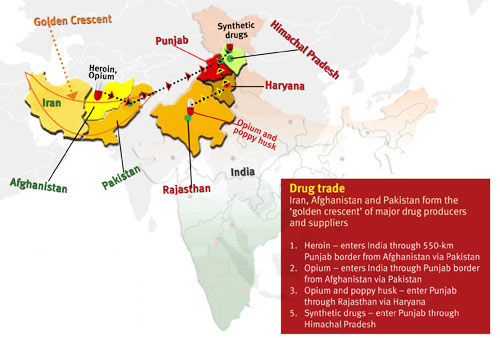

Blaming the situation on easy availability of drugs will not lead to a solution. Easy availability is ensured by a well established trafficking network. Often beginning its India journey from the Pakistan border (most originates in the poppy fields of Afghanistan before entering India via Pakistan), the tentacles of drugs reach the remotest of villages, creating a proliferate web of supply chain all over Punjab, and beyond.

Heroin is the main drug smuggled along the 550-km border that Punjab shares with Pakistan. The most popular method is to put a packet of heroin in plastic pipes and throw them over the fence on to the Indian soil. The smugglers from both Pakistan and India use SIM cards of Pakistan to stay in touch. This way Indian smugglers escape from coming on the radar of enforcement agencies, as the mobile towers in Pakistan near the Indian border catch signals from the Indian side too. Another way is to conceal the packets in farms on the Indian side at particular locations. This is done by Pakistani farmers who visit farms on the Indian side for work. The packets are later picked up by Indian smugglers.

Once the drug enters India, couriers play hide-and-seek with Border Security Force (BSF) officers. No transporter takes the drug more than 100 metres away. The drug packet is passed on to another person, who again moves 100 metres before passing the packet to another courier. This way a chain of couriers is formed to divert the attention and confuse BSF officers.

Villages near the border receive the smuggled drug the earliest. However, it does not reach addicts directly. In Tarn Taran, middlemen send in motorcycles and cars to distant villages for addicts to hop on and come to a specified place to buy the drugs. Social worker Sukhdev Singh talks about the growing drug trade in the district. “Dealers usually target a lone youngster and lure him into the business on the pretext of making easy money. They assure the youngster that in case he gets caught by the police, his family members would be provided for by them.”

In urban slums, where accessibility of heroin is less prominent as compared to villages, cheaper smack and prescription drugs dominate the drug market. It is here that pharmacists make the most of the vulnerability of addicts. Prescription drugs, mostly in the form of capsules, are usually meant for subduing mild depression. But if they are taken in large quantities, they provide a high similar to the effect of smack.

In Kot Khalsa kasba (a collection of villages), Amritsar, residents speak of open sale of prescription drugs at medical stores without any check for a doctor’s prescription or the quantity required. “Prescription drugs are openly sold here because most of the owners of medical stores are supported by influential people. Relatives of chemist shop owners are either influential lawyers or are in the police department.

This helps the pharmacists to continue their business without any fear,” says Sawinder Singh, councillor of ward no 55, Kot Khalsa. The local police, too, cashes in on the condition of addicts by asking them for bribes in return of not making an arrest, say residents. “While lower rank officers indulge in corruption, senior officials are too busy to take note of the situation,” says Sawinder.

Moving on, the drug makes its way towards bigger cities, such as Amritsar and Jalandhar. In the ongoing petition on the issue of drug abuse being heard in the Punjab and Haryana high court, Shashi Sharma has given the names of over 16,000 drug peddlers to the court.

Sharma explains how the inter-city system operates.

If an addict living in Jalandhar visits Amritsar but does not know where to find the dealer, he need not worry. He would need to follow a few simple steps and the drug would be delivered to him instantly. First, the addict would have to call the dealer (from whom he usually buys drugs) sitting in Jalandhar. The dealer would give a call to another dealer in Amritsar and give him the details of the customer in Amritsar, eagerly waiting for his dose. The Amritsar dealer would then call the customer and meet him at a specific place. He would charge for his services from the customer and leave without handing him over any packet of drugs. About five minutes later, the Amritsar dealer would call the customer and direct him to a specified place from where he could pick up the drugs. Usually, the packet is placed between two bricks kept on the ground at a particular point location. This way, the dealer gives the customer the sought drugs, charges for his services and the product, and also prevents himself from being caught red-handed, in case the customer turns out to be a policeman.

Weak enforcement

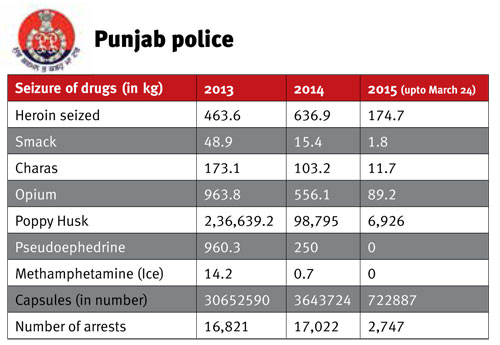

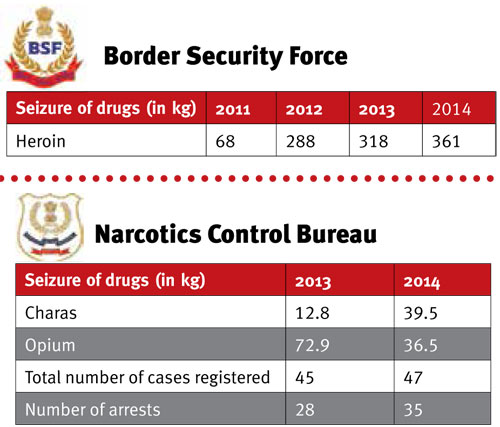

The enforcement agencies find themselves in a bind in eradicating drugs from the state. Apart from allegations of corruption, there are a number of hurdles that come in the way of enforcement agencies. While the Punjab police made thousands of arrests last year, it has often been accused of arresting drug users and falsely showing them as peddlers. The BSF, on the other hand, finds it difficult to keep a blanket check on each point of the 550-km long border, while the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) seems to be nowhere in the picture. Severe lack of intelligence leads to a little amount of seizure of opium and charas by NCB, while major seizures of heroin are handed over to the NCB (for destroying the drug) by the BSF.

Drugs for every pocket

According to the different economic classes, drugs in Punjab segregate themselves to cater to everyone’s needs. If the poor take smack and prescription drugs, the middle class injects heroin and the rich consume synthetic drugs. Largely coming from Himachal Pradesh, the laboratory-made synthetic drugs are highly expensive, with a droplet costing as much as '2,000. Though they are not as addictive as heroin, they are said to cause severe damage to the human brain. Depression, aggression, mood swings and dementia are the common symptoms of synthetic drug abuse. Popular in bigger cities, they are more of a weekend party drug. “The abuse of synthetic drugs usually starts from Friday evening, keeps going on through Saturday and finishes on Sunday morning. On Monday, the user goes back to his usual routine,” says Dr Bhola, pointing that here dependence and withdrawal symptoms are much lower.

In circumstances like these, Punjab’s future stands on a sticky wicket and is unlikely to improve soon. “It seems that Punjab has always been under the watch of an evil eye. First it was the partition, then terrorism, and now this poison,” says Sawinder Singh, councillor, Kot Khalsa.

yogesh@governancenow.com

NOTE: The names of drug addicts and their family members have been changed to protect identities

(The article appears in the April 16-30, 2015, issue)

Nandini Satpathy: The Iron Lady of Orissa By Pallavi Rebbapragada Simon and Schuster India, 321 pages, Rs 765

As many as 1,351 candidates from 12 states /UTs are contesting elections in Phase 3 of Lok Sabha Elections 2024. The number includes eight contesting candidates for the adjourned poll in 29-Betul (ST) PC of Madhya Pradesh. Additionally, one candidate from Surat PC in Gujarat has been elected unopp

The provisional figures of direct tax collections for the financial year 2023-24 show that net collections are at Rs. 19.58 lakh crore, 17.70% more than Rs. 16.64 lakh crore in 2022-23. The Budget Estimates (BE) for Direct Tax revenue in the Union Budget for FY 2023-24 were fixed at Rs. 18.

The much-awaited General Elections of 2024, billed as the world’s biggest festival of democracy, began on Friday with Phase 1 of polling in 102 Parliamentary Constituencies (the highest among all seven phases) in 21 States/ UTs and 92 Assembly Constituencies in the State Assembly Elections in Arunach

Fit In, Stand Out, Walk: Stories from a Pushed Away Hill By Shailini Sheth Amin Notion Press, Rs 399

The recent European Union (EU) policy on artificial intelligence (AI) will be a game-changer and likely to become the de-facto standard not only for the conduct of businesses but also for the way consumers think about AI tools. Governments across the globe have been grappling with the rapid rise of AI tool