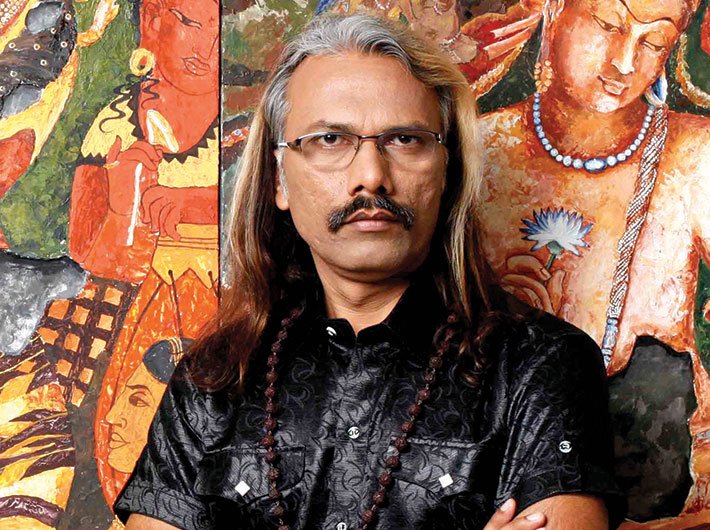

Imagine a jigsaw puzzle with the pieces for many areas missing. You are required to work out the missing parts, including what appears on them and the colours, and create a convincing whole. Now imagine the puzzle is a faded, discoloured fresco from the ancient Ajanta caves, of which you are creating a restored digital image that matches how it looked when it was painted more than 2,000 years ago. That painstaking work has been the obsession for 10 years for artist, photographer and restorer Prasad Pawar.

Having gone over photographs of the paintings square inch by square inch, Pawar has so far completed restoration of 14,000 square inches. He recently put up an exhibition of 70 digital restorations of images from Ajanta with the peeled off parts restored digitally – at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts (IGNCA) in the capital. These paintings are from Cave No 1 at Ajanta, but to be done with the cave, he’ll have to finish working on another 2,23,200 square inches. “And if I think of restoring all the paintings in all 30 caves in Ajanta, it might take me 120 more years,” he says.

Pawar’s love affair with Ajanta began in 1989, when he was a student of fine arts in Pune. That was when he first set sight on the iconic Bodhisattva Padmapani fresco in Cave No 1, a graceful, crowned figure of a bodhisattva, eyes lowered meditatively, in his hand a lotus symbolising bodhi or enlightenment. Pawar was in rapture, but the missing patches disturbed him. “Large portions were lost. The stomach and left hand were missing from this huge painting,” he says. “Something or the other was missing in the other frescos and reliefs too. I asked my teacher why these frescoes were left in such a poor state when they are part of our cultural heritage. When my teacher did not consider seriously my idea of working to restore them, I took it personally.”

Since then, he says, he kept thinking about the frescoes and how he might restore them to how they looked in the times they were created. He didn’t even have photographs to work with or inspire him to action: the Ajanta caves are a UNESCO world heritage site and the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) does not permit photography inside the caves. No one is permitted to touch the frescoes.

“It was 17 years before I got permission to photograph the cave paintings,” says Pawar. “It took a lot of time to make them understand what I wanted to do. They said there are already 500 books, many of them photobooks, on the Ajanta caves and my work would only add to that, so what was I trying to achieve? I had to convince them that the intention was not to put together another book.”

In those 17 years, Pawar kept his goal alive in his mind. “I’d keep thinking of how I might restore those paintings in some way,” he says. He’d visualise the paintings in his artist’s mind, imagine the unknown artists who worked on them, those who laid the base material in layers on the rock walls, those who prepared the pigments. He studied Pali at Pune university and got in touch with more than 50 language experts and experts on the Ajanta caves from across the world. He went through photo-documentations that others had done of the frescoes. He also read the 7th century Vishnudharmottara, an encyclopaedic Sanskrit work which sets out in one of its chapters the art of image making. Those were years of meditation, reverie, study, quest.

In 2006-07, ASI permitted him to photograph the frescoes without any artificial light. “Sixty to 70 percent of the paintings are not visible in available natural light,” he says. The challenge was to get good photos in the low light inside the caves. He started visiting the cave with his team and waiting for the light to peak for each painting. “There is indeed a perfect time to view each of the paintings. Figuring out the right time when natural light falls best on them was the first step,” he says. “We always celebrated when we got one perfect click in 10-15 days.”

Finally, proper photo-documentation began in 2009. Pawar and a team of 12 – artists and experts in Sanskrit, Pali and Magadhi Prakrit – simultaneously studied the intricate artwork, the colour palettes uses, the composition, the details. They took notes on ancient Indian social life, architecture, crafts and lifestyle. Travelling some 35,000 km across the country (covering parts of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, Odisha, Jharkhand, Bihar, Tamil Nadu and Kerala), Pawar collected references to artistic techniques used in the paintings.

“What makes physical restoration difficult is that we have little clue about the techniques used by artists of those times,” he says. “The Vishnudharmottara mentions some methods of wall preparation, using burnt conches, sand molasses, bananas and resins, and also some pigments made from volcanic rocks. But the painting sequence of those artists was unique and difficult to

replicate.”

Digital restoration, too, has its problems. “People tend to think digital restoration means we use Photoshop to fill in the missing patches,” Pawar says. “That’s simply not the case. We first have to make sketches to understand the impression the painting creates. The second step is colour correction. Over the years, the paintings have yellowed. Correction is carried out for clarity. Colour composition and treatment when natural light falls is unknown. It takes a lot of effort to get the colour tone that matches the original.”

Two major works of reference for Pawar were the works of Lady Christiana Jane Herringham and Ghulam Yazdani. Lady Herringham was a copyist and patron of the arts who from 1909 to 1911 copied out Ajanta paintings, with help from three students of Rabindranath Tagore – the illustrious Nandlal Bose, Samarendra Gupta, and Asit Haldar, later recognised as giants of the Bengal school of art. Yazdani, an art historian, made a photographic survey of Ajanta paintings and his work was published in four volumes from 1930 to 1955.

But it certainly wasn’t a matter of just looking at those references and trying to achieve a colour match. To complete his re-creation of the Bodhisattva Padmapani, for instance, Pawar collected evidence from the Pitalkhora caves, also in Aurangabad district, on which work is believed to have begun in the 3rd century BCE, almost a century before Ajanta, and the Bedse caves, near Pune. Pawar makes many sketches on canvas after studying the paintings in detail, and fills in the empty patches by looking through references. But the texture of canvas (or any other base) does not allow an acceptable enough match of the pigments with how they appeared on the frescoes. He then goes to work on Photoshop, with an outline and colour scheme ready. “The detailing is done on Photoshop, and getting the colours right is intricate and time consuming,” he says. For each digital reproduction to get clearance from the ASI, he had to give evidence for every tiny detail he had re-created. For the Padmapani painting, for instance, ASI objected to a ring on the bodhisattva’s finger. “I had to show them all the evidence to authenticate my work,” he says. “Finally, they had to agree.”

All along, Pawar has worked without any funding. Each square inch of work costs him Rs 15,000, borne by the directors of the Prasad Pawar Foundation which he has set up for this work. “It was our decision to come to people after we had finished some work. Now, we can ask for funding,” says Pawar, after the exhibition at IGNCA. The immersion in the restoration process has created a deep connect between Pawar and the paintings. Now, he wants others to communicate with them – through his digital restorations.

[email protected]

(The article appears in the March 15, 2018 issue)