Private hospitals make the unkindest cut -with upto 1,700% margins

Pratap Vikram Singh | February 1, 2018 | New Delhi

Gopendra Singh Parmar broke into tears several times while speaking of the last days of his eight-year-old son, Sourya, who died of dengue at the paediatric intensive care unit (ICU) of the Dr Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital, Delhi, on November 22. He hadn’t slept for days, and was drained physically and emotionally. Financially, too, for the Parmars had had to run from hospital to hospital in search of treatment – in Dhaulpur, Rajasthan, first, then in Gwalior, Gurugram and Delhi. And it was all in vain.

The Parmars are from Dhaulpur, 350 km from Delhi. Gopendra Singh sells life insurance for a living. Their son Sourya took ill on October 25; his mother noticed around 5 am that he was running a high temperature. The family took him to the Dhaulpur district hospital, where Dr Hariom Garg suggested blood tests to check for dengue. The tests were done at a nearby path lab and came out positive. He was admitted to the hospital and put on IV fluid. Over the next three days, the boy’s platelet count dropped from 1.55 lakh per microlitre to 21,000 per microlitre. This called for administering platelets. But the district hospital did not have a cell separator to isolate platelets from donors’ blood.

Doctors advised the family to take him to the Kamla Raja medical college hospital, Gwalior, about 65 km away. On October 28, he was admitted to the paediatric ICU ward where platelets were administered. The ICU ward, however, was cramped: two to three patients on the same bed. The Parmars were troubled by this. One alternative was to go to a hospital in Agra or Delhi.

Shourya Parmar with his mother

They first thought of AIIMS, in Delhi, and if that didn’t work out, Gangaram hospital, also in Delhi. The third option they had in mind was RML Hospital, also in the capital. So the next day, they took an ambulance – from Critical Care Ambulance Services – to take Sourya to Delhi. “We left hospital by 3.30 pm,” Parmar recalls. “While leaving from Gwalior, we didn’t have time to visit our home. I asked my mother to get whatever money we had and meet us at the bypass. I requested a couple of my uncles to bring a couple of lakhs,” says Parmar. He also made calls for financial help. “I had Rs 60,000 in my pocket, and another Rs 70,000 in my bank account. I anticipated I’ll take Sourya back home after proper treatment, which would perhaps cost Rs 2-2.5 lakh. Even so, I arranged for Rs 4 lakh.”

Midway to Delhi the ambulance driver suggested that since the boy needed urgent care, they should not waste time travelling to Delhi and instead go to Medanta hospital in Gurugram. (Travelling by road from Gwalior to Delhi, one has to cross Gurugram.) He was persistent. “Not once, twice, but several times, he asked us to take Saurya to Medanta. We didn’t want to take the risk. After initial hesitation, we agreed to what he was saying,” says Parmar.

It was around 11.30 pm on October 29 when the Parmars reached the private hospital. “As soon we arrived, the reception directed us to get a patient ID made for Sourya and I was asked to deposit over '1 lakh. I deposited Rs 75,000.” Till the time Parmar paid the initial amount and completed formalities, Sourya was kept waiting at the ground floor for about two to three hours. Later, he was taken upstairs to the paediatric ICU. “First investigation was done by 3 am. We were briefed about the tests only in the morning, around nine. The doctors told us that Sourya’s kidney, lungs and liver were failing and blood pressure was extremely low,” says Parmar. He was put on ventilator after a few hours.

“On October 31, I was asked to pay a couple of lakh of rupees for IVIG,” he says. IVIG, or intravenously delivered immunoglobulin, is known to be expensive. “I got repeated calls from the hospital; the hospital staff complained why we haven’t deposited the fee as they have to administer the immunoglobulin,” says Parmar.

In the third week of treatment at Medanta, doctors advised family to take him to some other hospital. “From November 14, doctors started preparing us to take Sourya away from the hospital. They said, ‘Here the child will take 20-25 days more to recover completely. Your financial position is not so good. Why don’t you take him to another hospital,” Parmar recalls. On November 20, he got Sourya discharged.

For the three-week treatment, Medanta handed Parmar a bill of over Rs 15,68,429. Saurya had been administered medicines costing Rs 6.21 lakh. Besides, there were approximately 3,000 consumable items like syringes, gloves, and wet wipes that alone cost another Rs 1,03,355. This added up to Rs 7,24,559.43. But there was more. The hospital billed Rs 3 lakh for ICU room charges. It billed another Rs 1,22,960 separately for anaesthesia and critical care (74 transactions). For doctors’ visits to the ICU – 85 times, as printed in the bill – the hospital charged Rs 63,750. It performed 183 lab tests (excluding radiology), which together cost Rs 1,52,145. For blood bank, Rs1,20,840. Under the ‘Gen S & Medicine’ sub-head, it charged another Rs 41,950. Sourya, as stated in the bill, was also taken once to the operation theatre and hence was charged an additional Rs 14,960. Although he was sedated, immovable and on ventilator, seven physiotherapist visits of “upto 20 minutes” happened between November 9 and November 17. A sum of Rs 3,500 was charged for that, too.

To pay up, Parmar, who manages his house on LIC policy commissions and income from a photocopying shop (altogther some Rs 15,000 per month), had to take loans from many close relatives. He managed to get together Rs 10 lakh. For the rest, he ended up mortgaging his house.

Burden of debt

Parmar’s story is not unique. In fact, medical treatment has forced several people into heavy debt or poverty. With national social and income surveys it has been known for decades that expenditure on health emergencies has been a major cause for driving millions of Indians below poverty line. The numbers run into millions: a WHO analysis based on 2011 data found 4.21 percent of India’s population – 52.5 million Indians – were pushed to deprivation ($1.90 per capita per day, by purchasing power parity) due to out-of-pocket expenditure on health, which constitutes nearly 70 percent of the current total expenditure on the sector. The WHO found that over 17 percent of Indians – translating to 216 million – spent more than 10 percent of their total budget on health.

Moreover, one-fourth of all rural households and a fifth of urban households are made to either borrow or sell assets to fund hospital stay, according to the national health profile for 2017, published by the central bureau of health intelligence, under the ministry of health and family welfare. With government hospitals in a shambles, the private healthcare sector, aided by lack of regulation, is flourishing. Till a few years ago, there was no need for a permit or licence for opening a hospital or diagnostic centre, though elaborate procedures for opening restaurants or cafes have been around for long. More important, there are still no regulations to prevent hospitals or labs from charging patients exorbitantly for anything they provide – and quite often patients have no way of knowing what unnecessary drugs, procedures or consultations are being forced upon them. The Indian healthare market is valued at $110 billion (2016), according to a joint study by industry body Assocham and research firm RNCOS. The study estimates that the sector will grow more than threefold to $372 billion by 2022. It will be no surprise if that value is reached sooner.

Govt doesn’t care

The state of government hospitals apart, government spending on healthcare is as low as 0.92 percent of the GDP; in contrast, the Indian population’s expence on healthcare is 3.93 percent of the GDP. “It may not exactly have to be a certain percentage of the GDP, as advocated by the industry or by international organisations, which come with their own agendas. But the government certainly must create the infrastructure required in rural and urban areas to meet people’s need,” says a senior paediatrician and a regular contributor to medical journals, including the British Medical Journal (BMJ).

Take Sourya’s case. When the platelet count fell drastically, the district hospital in Dhaulpur didn’t have the equipment to enable transfusion of platelets. He had to be rushed to a hospital in Gwalior, in another state. This hospital, also run by a state government, had limited ICU facilities. As a result, the Parmars were forced to seek out a private hospital.

“In rich countries, 90 percent of the people access healthcare in public healthcare. In India, still a developing economy, 90 percent go to the private healthcare,” says a senior gynaecologist at a private super-speciality hospital.

Nearly all policy and committee reports underline the importance of government intervention in healthcare. This includes the National Health Policy, 2017. Its objective is to “improve health status through concerted policy action in all sectors and expand preventive, promotive, curative, palliative and rehabilitative services provided through the public health sector with focus on quality”.

“The absence of government in healthcare has created a monstrous force (the profit-driven private, corporate hospital) which is not easy to tame,” says another senior doctor at a corporate hospital. The government needs to create an alternative model, says Dr Sanjay Nagral, surgical gastroenterologist, Jaslok Hospital, Mumbai. “The point is that there is no way the government will be able to check these private forces unless it creates a counter force.” The sector needs active intervention from the government to draw back people to public healthcare system. “The government has left the entire specialised care to the private sector and it’s a major problem,” he says.

For Nagral there are two key reasons why the government should regulate. First, to protect the interests of the people. Second, healthcare can’t be private-sector-driven. “It’s not as if the government doesn’t have money, but its priorities are wonky. It doesn’t want to spend on the social sector,” he says, and points to the dependence of senior government functionaries on private healthcare. They don’t want to be bothered with public healthcare.

Nagral also speaks of rationalisation of drug prescription and pricing. “In other countries, unless you have a proven infection, you cannot be given antibiotics. Here it’s a free-for-all! I am not sure any player is interested in rationalising prescriptions,” says Nagral. And a senior doctor in general medicine at AIIMS says, “Bangladesh and Sri Lanka have a rational drug policy. Why can’t we?”

The bill

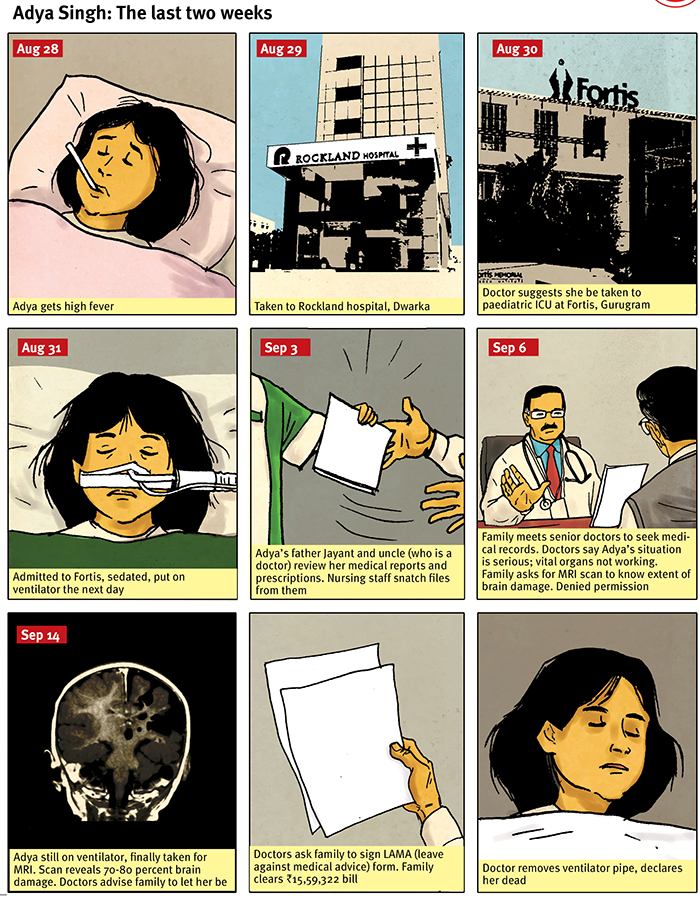

In September last year, a couple of months before Sourya passed away, a seven-year-old girl named Adya had succumbed to dengue after two weeks’ treatment at the Fortis Memorial Research Institute, Gurugram. Adya was put on ventilator the day after admission. Her family was handed a bill similar to that Sourya’s family received: about Rs 16 lakh.

Adya Singh

On August 28, when Adya caught fever, Jayant Singh, her father, took her to a local paediatrician. The doctor noted dengue symptoms. The next day, she was taken to Rockland hospital, where doctors confirmed dengue. For unknown reasons, the paediatrician advised Singh to take Adya to Fortis hospital for its renowned paediatric ICU. On August 31, she was taken to Fortis and was put on the ventilator from next day onwards. The hospital staff told the family that she would regain consciousness by September 3. She didn’t (she never did). The same day Jayant visited the paediatric ICU ward along with his brother-in-law, a doctor. While he was reviewing the patient record pinned along side Adya’s bed, nursing staff snatched the records from his hands and yelled that it is only meant to be seen by the hospital doctors as Adya was covered under insurance.

The parents were asked to wait till September 6. Seeing no improvement, a senior doctor met Singh and told them that the situation was critical. All this while the family asked the doctors for a brain scan to ascertain the damage. The doctors told them that’s virtually impossible with the ventilator.

On September 14 the doctors suddenly decided to get an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) done so as to know the exact status of her brain. Adya was taken for the MRI along with the ventilator. It was found that there was an extensive damage, of about 70-80 percent, in the brain. “We were called to a counselling room and told the brain damage was irreversible and we should let the baby rest in peace,” Singh recalls. “After September 6, we repeatedly urged the doctors to get a CT scan or MRI done so as to know her brain’s position. But we were always told that it won’t be possible with ventilator. It will be very risky, they said, if the girl was removed from the ventilator. Then how was it possible on September 14? They were screening every organ all this while, why did they avoid scanning the brain?”

In the end, Singh and his family members were asked to sign a LAMA (leave against medical advice) form. While transferring Adya into ambulance, a doctor pulled out the ventilator pipes and she was pronounced dead after two minutes.

After a few weeks, one of Singh’s friends tweeted the hospital bill and it went viral. Within a few days it was retweeted by thousands. Social media users criticised and trolled the hospital for pumping 650 syringes and using over 1,000 gloves during Adya’s two-week treatment. Similar numbers of consumables and drugs were used at Medanta in Sourya’s case. Later, the case was picked up by the media, as union health minister JP Nadda responded on Twitter, promising “necessary action”. A Haryana government-appointed enquiry panel indicted Fortis for grave negligence, unethical and unlawful acts and overcharging for drugs and consumables.

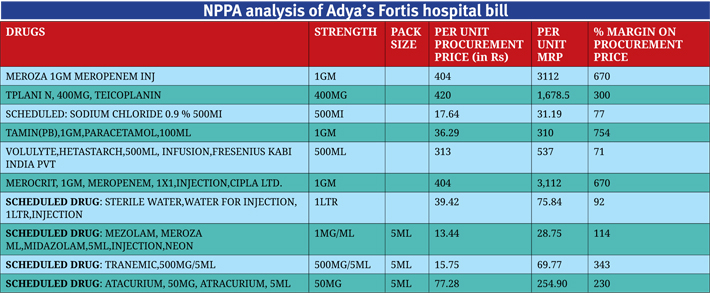

The National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority of India (NPPA), on Jayant Singh’s request, analysed the hospital bills and later posted them in the public domain, when they were sought under the RTI Act, 2005. The NPPA had asked Fortis to provide the rates at which it procured drugs and consumables. It categorised the bill in scheduled, non-scheduled drugs and consumables categories, and found that the hospital had charged from five to 1,700 percent mark-ups or profit margins! No doubt, the pharmacy charges constitute roughly half of the total bills in both the cases.

Take the use of IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin, used to boost immune system) in Sourya’s treatment, for example. Immunorel (5gms, 100ml) was sold at Rs 14,697 per unit. Three units were used on October 31 and then four units on November 1. For just two days, this medicine alone cost over Rs 1 lakh. According to a source, hospitals usually procure IVIG at less than

Rs 10,000 a unit. The benefits of bulk buying is not passed on to patients.

Similar practice is followed in cases of monoclonal antibodies, anti-cancer drugs, and powerful antibiotics, says a senior doctor who has worked at Medanta in the past. Meropenem, an antibiotic for serious bacterial infections, is another example. For Sourya, Medanta used Meronem 1gm (by Zydus Cadilla), priced approximately Rs 2,700. According to the NPPA analysis, Fortis procured Meropenem (Merocit 1gm by Cipla) for Rs 404 and billed it for Rs 3,112, a mark-up of 670 percent. On consumables, the Fortis mark-ups went as high as 1,000-1,700 percent. A “three-way stop cock, BI Valve” was procured for Rs 5.77. The hospital charged Rs 106. On disposable syringe without needle, Fortis charged 1,208 percent mark-up. It bought syringes at Rs 15.29 and sold them for Rs 200. On gloves, it earned mark-ups of upto 661 percent.

Yet, the most brazen was the high mark-ups on scheduled drugs, on which the government cap is 15 percent. The hospital procured ‘Tranemic, 500mg/5ml, Tranexamic acid’ at Rs 15.75 and billed it for Rs 69.77, the margin being 343 percent, according to the NPPA analysis. For ‘Fenstud, 500 mcg’ it charged a mark-up of 293 percent, procuring it at Rs 56 and charging patients Rs 220. Dotamin, 200mg, a nonscheduled drug used for treatment of heart failure, was procured for Rs 28.35 by Fortis and Adya’s family paid Rs 287, a mark-up of 914 percent. On enemas, it earned margins of 538 percent.

Enter the corporates

About three decades ago, the corporate sector started running hospitals in a big way. Over the years, private and trust-run hospitals too moved to having managers instead of doctors running the show. Now, even trust and charity hospitals in metro cities – Moolchand hospital and St Stephens Hospital in Delhi, for example – are run by CEOs and CFOs or by a board where doctors are in the minority. The motive is clear: profit. That is, unfortunately, at the centre of the entire private healthcare machinery – the profit, not the patient. That’s why corporate hospitals keep medicines, other pharmacy items and implants of a limited set of brands – from whom these could be procured at minimum costs and sold to the patients at the highest, without giving patients any choice, holding them captive.

“The management hires staff for sales and marketing – and some are hired from the hospitality sector for their suave looks and role similarities – and are paid plum salaries. Their job is to ensure footfalls. They work with doctors, set their six-monthly or annual targets for procedures and billing,” says the senior gynaecologist who works with a super-speciality hospital.

One of the many things marketing personnel at corporate hospitals do to ensure footfalls is creating and cultivating referral networks: doctors in private practice, owners and staff of diagnostic centres, etc., who will urge patients requiring hospitalisation or extended care to go to these hospitals. Such networks extend across states, and reach into small towns. Doctors working in government health centres and hospitals, the central government health scheme, ex-servicemen’s contributory health service and so on are also included in these networks. Ambulance services are also quite often part of these networks.

“That’s the biggest nexus. There is clearly a conflict of interest when a doctor refers a patient to another hospital expecting a cut. That’s the starting point of their supply chain network,” says an official working with a multinational device maker. “Local physicians will have a contract with corporates for smooth flow of payment.” A doctor who has worked with super-speciality corporate hospitals says non-medical professionals too get 10 percent of the hospital bill as incentive for bringing patients to a hospital.

Pushing doctors

Doctors at corporate hospitals are under immense pressure to deliver on targets – counted in rupees, that is, not patients’ recovery rates. “If, being a gynaecologist, I have high normal delivery rates, lower rate of caesarians, shorter stays at hospital for patients, least complications – all these are actually good. But I’m of no use to the hospital,” says a senior gynaecologist.

“Suppose 70 percent of my patients over a six-month period conceive with help of affordable medicines, whereas one IVF costs at least Rs 2 lakh, I won’t be a star for the hospital management. As we are talking, touts would have just brought patients who would be taken for caesarian operations without giving them a choice of second opinion.” The biggest stars are the transplant surgeons. Some are paid several crore rupees annually, the gynaecologist says. “Obviously, when you get that kind of salary, you have to bring business.”

The senior doctor referred to the paucity of patients and overcrowding of doctors at these hospitals. “In the past there used to be only one doctor in most of the towns. At present, the doctor-to-patient ratio in Delhi is higher than in New Jersey – the highest in the world. Too many doctors, a few patients and extremely few paying patients. So then what do you do? It is called milking the patient,” he says. Doctors ask patients to get more procedures done, prolong their stay at the hospital, have them admitted for illnesses which could have been treated at outpatient level. There is no auditing of the appropriateness and frequency of radiology scans prescribed to patients. “With drugs you have to prove efficacy. But for MRI you don’t have to. The number of scans depends on who is paying. It is completely unregulated,” the gynaecologist says.

Practices vary from hospital to hospital, but the pay structures incentivise those who encourage admissions and procedures and prescribe more. “It’s called faculty management practice (FMP), or say, bonus,” says the senior doctor who has worked with a corporate hospital. “The FMP comes from the increased numbers of admitted patients, particularly in the higher rental room, doing tests,” he adds. “I don’t know the guy personally, but a relatively young orthopedic surgeon left a corporate hospital last year because of the unnecessary knee implants he was forced to make. He says it made him sick to see pristine cartilage (healthy knees) being replaced,” the senior medico says.

When the focus is on numbers, it naturally leads actually to suboptimal care, unnecessary admissions, longer duration of hospital stay. “So you dispose of outpatients in five minutes. But you try to channelise them into investigations that will turn them into in-patients. The term ‘conversion’ is used officially for outpatient to inpatient, admission to surgery, etc.,” the doctor says. “Greater hospital profit equals higher bonus – I have seen cheques disbursed at Diwali time. More money means foreign off-site trips for the hardworking doctors,” the senior medico says.

It’s a thin line between offering the best, high-tech care and offering frugal but evidence-based care, the senior doctor says. “That’s something the health ministry should have figured out. The government wants to tango with private hospitals, withdraw the already dwindling support to the public system, and then cry foul when cases like these [Adya’s and Sourya’s cases, among others] are shown up. It’s an inherently dishonest stand,” the senior medico says.

Then comes the pharmaceutical companies and device makers. These companies are armtwisted by the corporate hospitals to sell their products at cheaper prices to the hospital with highest possible labeled MRPs. Pharma companies too have doctors in their fold. “They tell doctors to prescribe their drugs, which are made available in local pharmacies. Every time a prescription goes to the pharmacy, the doctor gets a certain commission,” the official says. At diagnostic centres, the cut for doctors is almost 50 percent, the official says. “That’s rampant – referral fee paid by imaging centres and diagnostic labs,” says the senior doctor. “Junkets sponsored by corporate hospitals, pharmaceutical companies are yet another unholy spin. It’s well known that pharmaceutical companies underwrite expensive dinners, foreign trips.”

Free-for-all

Although a legislation to regulate hospitals and clinics was in the works for several years, it was only in 2010 that the government enacted the Clinical Establishment Act, 2010. The objective was to register each and every clinic and hospital and ensure basic minimum standards. The proposed setting up of a national council for ‘clinical establishments’ was notified two years later, along with Clinical Establishment (Central Government) Rules, 2012. Health being a state subject, the implementation of the CEA rested with states. Four states – Arunachal Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Mizoram and Sikkim – and all union territories adopted it the same year. Later, it was adopted by Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, Jharkhand and Assam.

Under the law, some major initiatives to be undertaken included: a) registration of clinical establishments; b) setting up of basic minimum standards of services and facilities; c) setting up standard treatment guidelines (STGs) for common diseases; and d) rate regulations.

On its part, the centre has prepared the basic minimum facilities to be provided at clinics and hospitals and 277 standard treatment guidelines under modern medical practice. The registration work has to be handled by the states. This has been slow, says Dr Arun Gadre, who was part of the initial consultations on CEA and later on rate regulations. “Clinical establishments have to actively register on it. They have not done it in many cases. State governments are also not enthusiastic. It is a stalemate. There is no political will to go ahead and implement the Act,” he says. Generally speaking, implementation has been poor.

On regulating rates, the national council had appointed a sub-committee which met a few times, but eventually nothing came of it, with fierce opposition from corporate hospitals and the Indian Medical Association.

The national council decided to leave it to the states. According to the minutes of the meeting of the national council held on September 8, 2017, most states are yet to prescribe rates for procedures and services under the CEA. “Only a few states have constituted technical committees in this regard. The states were requested to take immediate action for determining the standard procedure cost for some common procedures. The rates of procedures and services should be transparent and should be inclusive of everything. Only one rate has to be informed to the patients and the same should be charged till discharge of the patient,” it said.

Referring the NPPA’s recent capping of charges for stents, knee transplants and medicines as a piecemeal approach, Gadre says, “Rather than capping stent separately, knee implant separately, non-scheduled separately, consumables separately, the government can make a list of a few hundred items which are used in medical care and fix a cost-MRP difference, based on wide consultation. Set up a committee, come out with a list of 600 items (for example), declare them under an ordinance that whatever company is manufacturing it will not mark MRP more than 20 percent. One-third of the cost will vanish in thin air,” he avers. “One single act can do the miracle.”

But can this happen? “I don’t have hope that the government is going to do anything about it. These are multi-million-dollar companies. They have large muscle power, they will always be influenced by lobbying,” he says. As of now there is no agency which collects data about the kind of treatment, tests and scans being prescribed at these hospitals. “The CEA has provisions for such oversight. However, the data collection authority has been given to the local authority – the district magistrate, who is already loaded with enough work,” he says. Again, its execution depends on states.

“A design flaw with the law is that it doesn’t have a clearly defined grievance redressal system,” says Sunil Nandraj, former advisor to the health ministry and a key participant in the national council meetings. “It further dilutes the entire purpose of having a regulation.” And Gadre calls it a “philosophical war”: “You can’t say both things – that health is a basic humanitarian service and on the other hand you rely on market forces.”

Malini Aisola, health researcher, All India Drug Action Network (AIDAN), says price control power rests with the centre, whether it is oil or rice or medicines. “Through the CEA, the idea was to have a legislation with provisions for rate regulation but it never made into the bill. The CEA bill was in principle very good. But the fact remains that it doesn’t provide the best of ways to do pricing regulation,” she says. “It was because of lobbying that rate regulation could never be made part of the CEA.”

Rather than waiting for states to take the lead, the centre must have provided a price control system. The centre may start with capping the charges for basic services which hospitals provide. It’s not an easy thing to do. “The government can set up an expert committee and can take up procedures one by one. There is nothing in law that stops the government from doing it. Under paragraph 19 of the DPCO, it is feasible, the way they did with knee implant and stents,” Aisola says.

Also the Drugs and Cosmetics Act and rules covers 23 categories of devices used in medical care. As of now only four categories – coronary stents, drug-eluting stents, condoms and IUDs – have been covered by price capping. “All 23 categories of medical devices which are deemed drugs under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1945, need to come under price control,” she says.

The larger question

Back to the Parmars. On November 20, the family took Sourya to the RML hospital, where he didn’t even survive for 43 hours. Parmar alleged that Medanta didn’t inform the family about Sourya’s condition. Beside dengue, Sourya had caught micosis, a severe fungal infection causing nerve rupture and bleeding, Parmar was informed at the RML hospital.

Parmar says that at this government-run hospital, senior paediatrician Dr Devki Nandan asked him: “Didn’t the Medanta doctors tell you anything about how bad the condition Sourya was in?” The doctor said there was no surety that the boy would survive. “Medanta doctors have used heavy doses of branded medicines. The generic medicines we prescribe won’t work on him now. We can try if you can buy medicines prescribed at Medanta from outside,” Parmar quoted a paediatrician at the RML hospital as saying. (Governance Now tried reaching Dr Devki Nandan but he didn’t take the calls.)

According to the government hospital records, Sourya had persistent “high-grade fever, falling blood pressure and worsening shock”. He had internal bleeding, of about half a litre, near the stomach and intestine area, possibly due to invasive mucormycosis – caught during a period of low immunity. It was followed by a cardiac arrest. The doctors followed clinical protocols, “but he could not be revived” and records say he was “declared dead at 5.50 pm”.

Had it not been for a reporter of a news television channel, who bumped into Parmar a day before while he was buying medicines from a pharmacy near the RML hospital, Sourya’s case would never have come to light. His case was flashed in the media for a few days and was then allowed to die its own death. At present, Parmar is running from pillar to post, from the office of Haryana health minister Anil Vij to the office of union health minister JP Nadda, for authorities to probe if his son was treated appropriately and ethically at Medanta and file an FIR against it.

The government surely has some questions to answer: Is it justified for an Indian to pay '16 lakh for treatment of a disease as trivial and preventable as viral fever? Is it justified for patients and their families to travel several hundreds of kilometres to metros to get treatment? Is it justified for the government to shun its responsibility and leave healthcare – including specialised care – completely to the market forces? Is it justified for private corporate hospitals to charge 300 to 1,700 percent mark-ups on drugs and medical consumables? Is it justified to have an inefficient drug control system which encourages doctors to go for branded medicines? Is it justified not to prevent a preventable disease through regular garbage clearance and vector control? There are no answers forthcoming.

Dr Amit Sengupta, of the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, a voluntary group, sees the cases of Sourya and Adya as the tip of the iceberg. “When we speak of Parmar and Singh, we’re speaking of a tiny section of the population who can afford to go to private hospitals, even if by mortgaging assets. Over 90% of the population, especially in villages and towns, manages with poor and unaccountable public and private healthcare. Several Souryas and Adyas lose their lives every day in rural India and it goes unreported.”

pratap@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the February 15, 2018 issue)

Nandini Satpathy: The Iron Lady of Orissa By Pallavi Rebbapragada Simon and Schuster India, 321 pages, Rs 765

As many as 1,351 candidates from 12 states /UTs are contesting elections in Phase 3 of Lok Sabha Elections 2024. The number includes eight contesting candidates for the adjourned poll in 29-Betul (ST) PC of Madhya Pradesh. Additionally, one candidate from Surat PC in Gujarat has been elected unopp

The provisional figures of direct tax collections for the financial year 2023-24 show that net collections are at Rs. 19.58 lakh crore, 17.70% more than Rs. 16.64 lakh crore in 2022-23. The Budget Estimates (BE) for Direct Tax revenue in the Union Budget for FY 2023-24 were fixed at Rs. 18.

The much-awaited General Elections of 2024, billed as the world’s biggest festival of democracy, began on Friday with Phase 1 of polling in 102 Parliamentary Constituencies (the highest among all seven phases) in 21 States/ UTs and 92 Assembly Constituencies in the State Assembly Elections in Arunach

Fit In, Stand Out, Walk: Stories from a Pushed Away Hill By Shailini Sheth Amin Notion Press, Rs 399

The recent European Union (EU) policy on artificial intelligence (AI) will be a game-changer and likely to become the de-facto standard not only for the conduct of businesses but also for the way consumers think about AI tools. Governments across the globe have been grappling with the rapid rise of AI tool