The plan is to electrify every rural home in India by 2018. But the ground reality shows that many poor villagers may not be able to pay for it, putting a question mark on the initiative

Dusk is about to fall and dark clouds hover over the sky. Deependra, a 10-year-old specially challenged boy, wears a tattered t-shirt and sits on the mud floor of his small hut. From time to time, he squeals and jerks in excitement. His eyes are fixed on an electronic equipment installed inside his hut.

He is enthused and so are the other children and adults who stand next to him. After all, everyone is seeing a white LED bulb and an electronic meter in the village for the first time. The bulb could light any minute as engineer Ravi Teja and his team have been working in their village for the last 20 days.

And the moment arrives; the bulb glows. The mood is electrifying as the expectant faces lighten up.

Mirzapur Basant village finally has electricity. An electric meter, a switch board and an LED bulb have been fixed in each of 10 households. Deependra’s mother Rambeti’s home is one of them.

Almost 40 km from Budaun city in Uttar Pradesh lies Mirzapur Basant. There are 100-125 households, which are being covered under the Deendayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana (DDUGJY) – a scheme through which electricity will be provided to all rural households by 2018, as prime minister Narendra Modi promised in his Independence Day speech of 2015. The centre pays for 90 percent of the scheme, while the state government foots 10 percent of the cost.

Budaun district has the highest number of un-electrified villages in the state. Out of UP’s 1,529 un-electrified villages, 409 are in Budaun.

Mirzapur Basant is one of those villages struggling with a perception that electricity is dangerous. “There were orthodox notions attached to it,” said Ram Chandra, a retired government teacher. “There was no excitement for electricity among villagers till a few years back when electricity reached a nearby village. People realised how life in that village changed. That changed their thinking,” he said.

The contrast became stark when people from other villages refused to marry their daughters in Mirzapur Basant. Bunwan Singh, a labourer, said that marriage proposals for his sons did not turn positive due to absence of power supply. “They questioned how our daughters will survive and refused to take forward the proposal,” he said.

Chanchal, from Bardhaman, West Bengal, got married eight years ago in Mirzapur Basant. She laments her plight of spending all these years in the flickering light of kerosene lamps. “I could not watch TV which my parents gifted me. It remains packed in a big aluminum box. My husband keeps telling me that electricity will come one day. I have already spent eight years and now I am excited to take out my TV,” she chuckles.

Her thrill didn’t last for long as she was told that Rs 3,000 had to be paid to get the electricity connection. She was not aware that electricity connection which includes the electronic meter and an LED lamp will be provided free of cost to only below poverty line (BPL) families. According to the scheme, above poverty line (APL) households will have to pay for their connection and no subsidy would be available to them. Chanchal now has doubts whether she should spend to avail the facility.

Affordability is a major factor in the entire rural electrification programme. There is a question mark on the rural populace paying up to get electricity.

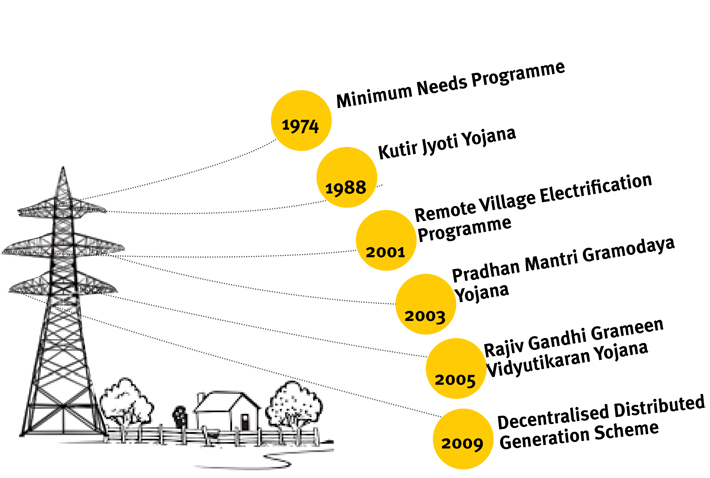

In the past too, the rural electrification scheme under the 10th and 11th five-year plans faced the same roadblock. DDUGJY, which was earlier called Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Vidyutikaran Yojana (RGGVY), has failed to have an impact in states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand.

‘Access to Clean Cooking Energy and Electricity’, a survey done by the Council on Energy Environment and Water along with Columbia University, in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal showed that nearly 50 percent of the people don’t have electricity while nearly two-third of the remaining households did not take electricity despite having power connection in the vicinity.

To ensure that DDUGJY doesn’t face any financial impediments, the centre has categorised states into two groups – the special category states which include all the northeast states, Jammu and Kashmir and Uttarakhand, while the second category includes the remaining states. For all states other than special category states, 60 percent grant is being provided by the centre for the commencement of the project while the central banks and financial institutes will bear 30 percent cost. The state owned discom, on the other hand, will have a contribution of only 10 percent.

The power ministry will release 10 percent of the grant on the approval of the projects by the monitoring committee. It includes an agreement among discoms, the state government and the Rural Electrification Corporation (REC). The next 20 percent tranche will be released after the discom places its confirmation letter of contract. The remaining 70 percent will be released only after the utilisation of the first and second instalments.

In the special category states, the state government contribution shall be five percent. The remaining cost will be borne by the centre and banks.

Cost-bearing capacity

Electricity reached Chandanpur village, seven kilometre away from Budaun city, in the month of June. So far, meters have been installed in 24 homes and eight are yet to be installed. There was a sense of excitement among villagers. But they were unaware of the monthly charges.

“We have not been told about the charges and the electricity bill so far. Therefore, we run only one fan and a bulb,” said Omveer, who owns a small grocery store and also works as a farm labourer.

He said if the bill was beyond his budget, he would bring down the consumption. “Definitely we will run a few devices, else will see whether to continue with it or not,” he said.

Atarkali, a housewife, prefers to use electricity for charging the mobile phone and to switch on one LED bulb. “My husband is a labourer. Look at our condition. I don’t know how much we will be able to pay,” she said. Her husband earlier used to go to another village to charge the phone.

Vivek Sharma, the monitoring officer for Budaun district appointed by REC, the nodal agency for the implementation of the scheme, said, “Households covered under the 11th five-year plan having unmetered connections are paying '125 a month whereas metered ones are paying '1 per kilowatt consumption per hour. This will continue.”

He said that for the new connections, bills will be generated after three to four months and users will have to visit the nearest power sub-station to pay the bill. But the question still remains as to how many will be willing to pay up.

As per the National Sample Survey on India’s agricultural households, an average farm household makes '6,426 a month. But over 65 percent of households are not able to make ends meet. They are indebted as most of their expenditure is on seeds, fertilisers, pesticides, irrigation cost, machine maintenance, interest on bank loans, rent for land, diesel, labour and other expenses. This excludes other household expenses like meeting daily food requirement.

Amidst all these expenditures, are Indian farmers ready to bear extra electricity cost?

When I spoke to some of the villagers, there was a disconcerting feeling that they would rather get electricity which is highly subsidised, if not totally free.

Villagers opt for an illegal and easy way out so that they don’t have to pay the electricity bill. I visited Mallahpur village where (barring four-five households which received meters under DDUGJY), majority had ‘katiya’ connection, a local term to describe illegal wiring that directly taps into the electricity supply lines.

Another village, Bamiyana, had the same scenario. Here people took illegal connections through the transformers used for running tube-wells. Since electricity has been a political issue to lure the electorate, apparently no action is being taken against the violators.

But power theft affects the revenue generation of the state electricity board. Already distribution companies are in poor financial health. It is for this reason that several villages in Budaun which were once electrified are now in the un-electrified category after they failed to pay their bills and illegal connections went up.

It was almost 10 years back that people of Mausampur village proudly availed electricity. Back then villagers had two to three electricity phases. The numbers were, however, few. Instead, a large chunk of the village population had illegal connection. It led to heavy load on the transformer which exceeded beyond the capacity. Technical glitches were reported and the transformer turned into a non-functional piece of machine.

A new transformer was not installed. It’s been eight years now and people are living without electricity. Technical glitches were not rectified, perhaps due to the fact that authorities were receiving a meagre amount through electricity bills.

“Why will they install a new transformer for just 10-15 families?” questioned Mohammed Shafiq, one of the residents of the village. “Nobody was willing to have an electricity connection because of the cost factor and was relying on ‘katiya’. So, there was no consideration for our village, even though it has been a complete blackout for months and years now,” he said.

Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana (DDUGJY)

Keeping in view the problems, the ministry of power has launched Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana for rural areas having following objectives:

- To provide electrification to all villages

- Feeder separation to ensure sufficient power to farmers and regular supply to other consumers

- Improvement of sub-transmission and distribution network to improve the quality and reliability of the supply

- Metering to reduce the losses

Under DDUGJY, ministry of power has sanctioned 921 projects to electrify 1,21,225 un-electrified villages, intensive electrification of 5,92,979 partially electrified villages and provide free electricity connections to 397.45 lakh BPL rural households.

Under the programme, 90% grant is provided by central government and 10% as loan by Rural Electrification Corporation (REC) to the state governments. REC is the nodal agency for the programme.

Financial provisions:

- Scheme has an outlay of Rs 76,000 crore for implementation of the projects under which government of India shall provide grant of Rs 63,000 crore

- A total of Rs 14,680 crore worth projects have already been approved

The rural electrification scheme this time, however, tries to curb the issue of power theft by directly changing the quality of the cable wire.

Manish Sharma, district vidyut abhiyanta who looks after the implementation of the scheme, said: “Initially the wire that was used for power supply was not insulated. So, people directly put ‘katiyas’. Now, we are using cables so power theft would be difficult.”

Quality and reliability

DDUGJY addresses the issues of accountability, reliability and quality by segregating feeders for agricultural and non-agricultural purposes. Domestic connections are fewer than the agricultural connections in rural areas. Therefore, new distribution transformers are to be installed or existing distribution has to be augmented as per the scheme. The purpose is to improve the hours of power supply in rural areas and reduce peak load.

Uttar Pradesh has been struggling to meet the energy demand. According to Load Generation Balance Report, UP faced a shortage of 12.5 percent of energy in 2015-16. Meanwhile, in 2016-17, Uttar Pradesh will have an energy deficit of 6.4 percent. It requires 110,850 MU (mega unit) but 103,806 MU of energy is available.

Considering all these factors, it can be said that though electricity cables will reach every village by 2018, whether every household will have an electricity connection or not is a big question.

Two brothers’ long, lonely battle

Electricity poles have thrice been erected in Hathni Bood village in Dataganj block of Budaun. Each time it was during an election season when a ray of hope was sparked among the village folks who looked forward to their homes being lit up. But then nothing happened. Even electric cables were not hung on those poles.

Years passed and the poles corroded, with hopes of villagers rusting away. Yet optimism was still left in 25-year-old Abdul Wahab and his 20-year-old younger brother Akhlaq Ansari, the sons of the village head, Abdul Razak. The duo made relentless efforts to get their plea heard.

“We wrote several letters to our MLA Sinod Kumar Shakya [a Bahujan Samaj Party leader]. But there was no response. Then we wrote several applications to chief minister Akhilesh Yadav. During his visit to Budaun we conveyed our appeal to him but nothing happened,” said Akhlaq, who even tried approaching Dharmendra Yadav, member of parliament from Budaun. “There was no response from him either,” he rued.

Abdul read about DDUGJY and wrote a mail to the prime minister’s office. His plea did not go unheard. He received the information about the Rural Electrification Corporation (REC) monitoring head of Budaun district.

Abdul contacted Vivek Sharma, who was appointed by REC last year. In February, he shot off a mail to which Sharma responded immediately. “It was for the first time in my career that somebody who desperately wanted electricity made an extra effort,” said Sharma.

Hathni Bood is a village of over 2,000 voters. Farmers are dependent on diesel to run tube wells to extract groundwater. Diesel worth '50-60 is spent on a day.

“When electricity comes, it will ease the financial burden and increase the overall productivity,” said Abdul Razak, the village head. Even for routine activities, households are dependent on kerosene oil and solar energy to charge phone batteries.

“Some houses have solar panels here. So, they are able to charge their mobile phones and use small, battery operated LED lights,” said Chheda Lal, a BPL card holder.

Incidentally, villagers initially were not keen to have electricity at their homes. When electricity poles were erected at their doorstep, they feared electric wires might prove fatal during monsoons. “They were not ready to get poles erected right in front of their houses. Engineers and labourers faced difficulties in convincing people,” said Sharma.

He then sought Abdul’s help to convince villagers to cooperate with the engineers. “We had a meeting with the entire village. We asked them to support without any inhibition,” said Abdul Razak.

Work finally started in July. Wires were now being laid out. Akhlaq, who is pursuing MA in English, is now keen to open his computer coaching centre in the village.

“I have grown up studying only in the daytime. Almost all children follow the same routine because we cannot study at night. When electric power will reach every household, our perception towards education will also improve. My computer coaching centre will take them one step ahead,” said Akhlaq.

His brother Abdul, who runs a computer centre in the nearby village by using solar panels, said, “Work will speed up. There will be more awareness about governance project; services will reach more people. Overall, we could all be a witness to development.”

There is hope among people. Bhagwan Devi, a tailor, stared at the LED bulb and muttered, “I’ll be seeing electricity for the first time in my life. I will ask my husband to get an electric motor installed in the stitching machines. I cannot wonder how our life will change after power supply starts.”

On whether the villages are upset with the government for the delay in providing electricity, the answer is a collective no.

Lakhan Ram, an octogenarian bluntly said, “Hum naraaz kyun honge? Sarkar hamse naraaz hai, tabhi kabhi bijli nahi aayi. (Why should we be upset with the government? Instead the government was upset with us. That’s why we didn’t get electricity.)”

archana@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the October 1-15, 2016 issue)