As political parties tried hard to woo the voters from all sections of society they forgot one major vote bank – the homeless

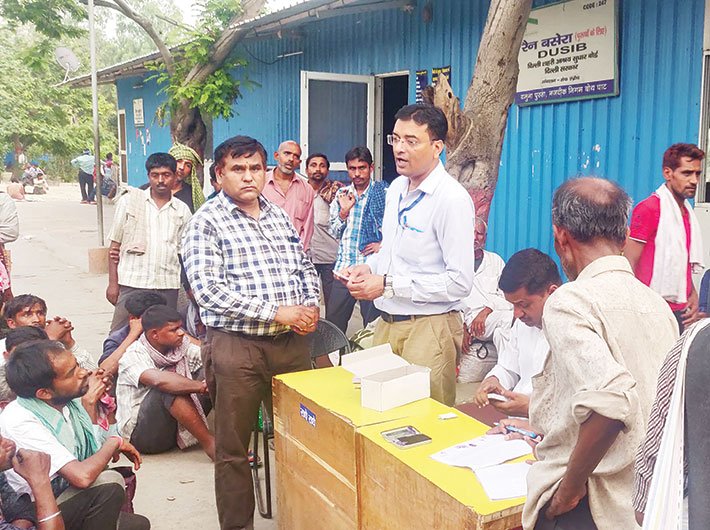

It’s 6 pm and there is no relief from the scorching heat. A serpentine line of 600-odd men extends for over half a kilometre near Yamuna Pushta night shelter. Ranging from ages 21 to 70, wearing tattered and scrubby clothes, the men wait for their turn as the election officers call out their names.

“Manto,” says one officer and a man in checked shirt and dirty black pants comes forward. Not resembling an inch with the literary genius Saadat Hasan Manto, the man wipes his face with a soiled gamcha and gives his thumb impression on a paper. He collects his voter identity card and leaves the queue, in all probability not even aware of his famous namesake.

Both the Mantos, however, share the same fate – of being homeless. One died yearning for his home in a country which he could never call home. The other strives to get a “homeless” identity. Both in their 40s, one lives to tell his tale, while the other left the world after making people uncomfortable with his tales.

Manto of our story is a homeless man. He hails from Hans Desh village in Jodhpur, Rajasthan. In 1993, the uneducated man moved to Jaipur looking for better employment opportunities. Disappointed, he moved to Delhi and has been living as a homeless daily wager in the city for past 24 years. He does odd jobs like rag-picking, loading shipment to transport vehicle, riding a rented rickshaw, helping at local restaurants around Kashmiri Gate and Chandni Chowk. “Finding job without any home or roots in Delhi is tough. To find a permanent job we need a guarantor – nobody trusts us,” he says.

Hence since 2013 his quest for getting a voter identity card began. After 11 failed attempts, on May 1 this year he finally got his voter card, which bears his strange address: “Address: 0, homeless person Yamuna Bazar, Yamuna Pushta, Delhi.” Nonetheless, Manto is happy and looks forward to voting. “Yes, I’ll vote. I have always heard that voting is the universal right of every individual. But for people like us it’s a dream and the only way to prove that we exist,” he says.

The two-day camp to give voter cards to homeless in Delhi was organised by the election commission of India (ECI). Out of total 881 homeless living near Yamuna Pushta area, 490 people registered to get their voter identity cards but only 335 got it.

As the whole country goes for voting this parliamentary election, the voting rights of the poor, underprivileged and floating population has been an issue. But the case of homeless voters rarely made its way into the national debate.

On April 6 and 7, the ECI organised registration camps for homeless voters at 198 permanent night shelters across Delhi, which houses 16,000 homeless people. Of this, only 2,712 people filled the form this year for voter cards, but merely 1,763 got them. Over 40 percent of the registered data was rejected by the EC. Explaining this, Ranbir Singh Delhi’s chief electoral officer, says, “Either the people already have the voter identity card, or they failed the verification test.”

To organise such camps, the ECI tied up with the Centre for Holistic Development (CHD) this election season. Homeless people were provided help in filling registration forms and getting their IDs at these camps. But this was not enough, explains Sunil Kumar Aledia, founder, CHD, who says that registration of homeless voters can’t be done in a day or two. “It’s a lengthy process. We are only organising the camp at night shelters. But our estimate says Delhi alone has more than two lakh homeless people. We need at least one month to reach out to them,” he says.

There are lakhs of people who sleep on streets, parks, and below the bridges in the city. Also, out of the 70 assembly constituencies in Delhi, zero voter IDs were issued at 30 constituencies (see box on pg.14). Reason: hardly anyone came.

For the homeless, getting a voter card is not a priority as they have more pressing issues like food and shelter. Darshan, 60, agrees that voting is an important civic duty, yet she also asks what difference it would make to people like her as nobody from any political party has ever visited them. She got her voter identity card at the two-day EC camp near Baba Kharak Singh marg. Flashing her ‘0’ address identity card, she says, “Our only priority is to find work, food and a place to sleep. It’s difficult to find a bathroom. People look at us and do not allow us to get inside the stores. Why would I even think of elections and voting?” she says.

Having spent more than half of her life at the street near Bangla Sahib Gurudwara in New Delhi, for Darshan getting a voter identity card is not about exercising her fundamental right it’s just a way to get entry into the formal sector. “Voter ID card is important for me. It’s the only identity proof I have till date. Maybe I can get some permanent sort of work after showing an identity card to the authority, they can trust me now. But do we even matter for the parties?” she asks.

Moreover, currently it’s the responsibility of homeless people to get themselves registered with the ECI, but this approach and methodology needs to change. “The people who are coming for registration are not the most vulnerable. The most vulnerable are those who have been living on the streets for extended periods and have mental disability, a physical illness, a drug or alcohol addiction, or a combination of all three. We need effective machinery and extended time-duration for them,” says Aledia.

While submitting registration forms for voter identity card, one needs to attach a photograph along with age proof and address proof. But homeless voters are exempted from submitting their age proof. For address they can give any specific place – ‘under the tree’ or the name of any road, bridge or park. Then three-time verification is held by an election officer who visits the place mentioned in the address column form of the homeless voter.

Even this process is tedious for a homeless, says Devesh Gupta, one of the caretakers of the Yamuna Pushta night shelter. “They can’t afford a photograph. The maximum number of forms filled on April 6-7 at Yamuna Pushta night shelter was 490. We purchased printers from our own pockets, sat with people and filled the forms for two days relentlessly. Two days is too little to do the work. We tried our best,” he says.

Also, the political will behind making these people exercise their franchise is lacking. It was only in 2013 that the process for registration of homeless voters first begun, that too after years of advocacy efforts by non-governmental organisations and civil society groups. A survey conducted by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in 2010 found that there are 56,000 homeless in the national capital. However, activists argue that the original number could be at least four times more.

Admitting to some loopholes in the system, Ranbir Singh says, “The ECI is trying to reach out to all the people above 18 years. Majority of people have registered themselves. But special camps are being set up for those who cannot get the voter card easily like the third gender, homeless, disabled people and people living in slums. But, yes, we need to sensitise the machinery.”

None of the three major political parties of the capital – BJP at the centre, AAP in the state and opposition Congress – have mentioned anything about the homeless in their manifestos. The number of registered homeless voters in the city is 9,600 – a figure which is not of any importance to political parties this year. During the 2015 assembly elections in Delhi, the Congress had promised to build homes for migrant labourers if it came to power; while the BJP and AAP had promised to increase the number of shelters for the homeless.

Yet, eventually, the ECI efforts bore fruit, as there was 61 percent turnout of homeless voters in Delhi on May 12.

deexa@governancenow.com

(This article appears in the June 15, 2019 edition)