The exodus of Hindi-speaking labourers from Gujarat is symptomatic of the social perils of identity politics

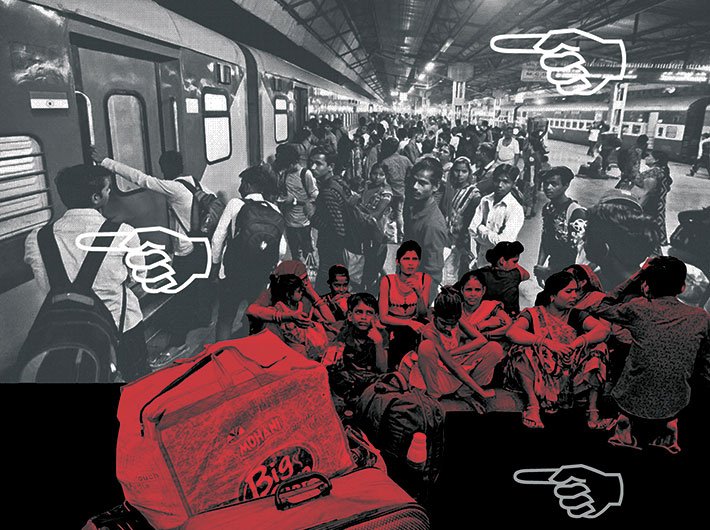

For the past fortnight, Gujarat has witnessed an exodus of migrants from Hindi-speaking states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The migrants, mostly of the labouring classes, have been attacked by locals after a 14-month old girl was raped, allegedly by a Bihari whom the police have arrested. The rape survivor is from the Thakor community, an OBC group which has in recent decades gained a great deal of influence. Those boarding trains and buses to flee say the violence against them is from the Kshatriya Thakor Sena, of which the chief is Alpesh Thakor, the Congress MLA from Radhanpur. Thakor has also made an inflammatory speech indirectly urging his community to clear the state of migrants, though he now says he wants to promote peace and would even go to Bihar to reassure migrant workers that they could return without fear.

Across the world, these aren’t good times for migrants. But Gujarat has been a safe haven, where generations of south Indians, Maharashtrians, Sindhis, and Hindi-speakers have all lived, worked, and prospered. It was always so. The legend is that Sultan Ahmed Shah I, who founded Ahmedabad in 1411, led a frugal and pious life and so the city was blessed: anyone who came here seeking a livelihood would not return in vain. Indeed, many migrants have settled down in Ahmedabad and the rest of Gujarat, adapting local customs and learning to speak and read Gujarati. The state’s mercantile traditions, its centuries old seafaring connections with Persia, Arabia and Africa, the travels abroad of its own people have contributed to this openness.

Unfortunately, that is changing. New social and political dynamics and the magnification of prejudices on the internet and the social media have played a big role in this. In fact, rather than be shocked that it is happening in Gujarat, governments ought to worry that it is happening everywhere. For the attacks on migrants in Gujarat are no different from the lynching of people in some other states on suspicion that they are child-lifters or otherwise criminally inclined. In those cases too, the victims were ‘outsiders’ of varying degrees. There have been cases from Maharashtra, West Bengal, Assam, Tripura, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Telangana, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu – and one in Ahmedabad itself. These were fuelled by WhatsApp rumours and the government was forced to ask the company to restrict ‘forwards’.

But the malaise runs deeper than that. There is a sense of insecurity everywhere, with a concurrent assertion of identities and a growth of insularity. When there are flash points like the rape of a child by a migrant, it has become easy to inflame anger and channel it against a whole group, holding it responsible for the crimes of one or two elements. There is no telling where it will happen next, and which group will face attacks.

In India, migration is a pressing problem because agriculture is no longer a viable livelihood. Besides, there are no jobs in villages and semi-rural areas. The more prosperous states and many big cities have become magnets for migrants, mostly the poor from rural backgrounds. It isn’t as if migrants choose particular states to go to. They rely on informal networks, driven by relatives who call them after settling down to a good job or business somewhere. Then there are traffickers, suppliers of cheap labour who make a killing by bringing villagers to work in the cities or towns. It is a symbiosis: the factories and small industries need cheap labour, and migrants supply it, living quiet, alienated lives, marked by heavy work, loneliness, and addiction to alcohol, drugs, porn, paid sex. Often, they also get involved in altercations with locals or in crime.

Governments have never paid attention to the needs of such migrants. They live in ramshackle shanties, paying rent to slumlords. Their children go without education. Migrants without regular jobs are forever on edge. Access to healthcare is minimal. It’s only after living in a state for such time as gives them voting rights do they manage to strike bargains with local politicians. But they are always considered expendable, other than during election time. Given a law and order system that almost never works, migrants are among the most vulnerable of groups. States have never planned for influxes of migrants. Our biggest cities, leave alone small towns, have never had living spaces where for a small daily fee, migrants can live under a roof, with running water, clean toilets, free medical care. Governments do little to pay migrants back for letting development ride on the backs of their cheap labour.

The Gujarat government could show that it wants to make a difference by ensuring first that police protect migrant enclaves and urge them to stay back. Locals should be encouraged to mingle with migrant communities and set up committees to resolve issues arising from crime, such as the one that started off the current exodus. Most importantly, police should act against those fanning hatred and ensure that they are punished. Politicians, especially, should sincerely work against divisive tendencies and refrain from using identity politics to further their interests.

But that is going to be a tall order. The new politics, frighteningly being seen across the world, is one of reaction against the very forces of globalisation that are fuelling prosperity and development. Identities, however amorphously defined, and however unreasonably seeking validation through a negation of the other, have become important in politics. In India, this amounts to a potent explosive, of which the ingredients are religion, caste, region, language, and class, in their many permutations. Migration complicates these factors manifold.

What is worse, political parties that have exploited the angst of identity to gain ascendency happen to be in power. Their politicians have no qualms about summoning forth a bogeyman to attack for the failures of a nation. Equally, they are willing to rewrite history as they want to see it. Jobs are hard to come by since the economy is sluggish, and governments are pushing nativist hiring laws. Gujarat, for instance, is making it compulsory for industries to hire high percentages of locals. In such an atmosphere of hatred and intolerance, it doesn’t help that you fit into categories of religion, caste, and language that you think are safe. You will never know what permutation or combination of those categories will be used to slot you, target you, kill you.

sbeaswaran@governancenow.com

(The article appears in October 31, 2018 edition)