The government is setting a new example in city governance by adopting special purpose vehicle (SPV) model under the smart cities mission. Basic challenges in city governance, however, remain

If things go as planned, India will have a set of clean and livable urban localities in the coming five years. These localities will be small islands of excellence in cities. They will have assured water and power supply, smart waste management, walkway, security of women and children and electronic governance, among others. Thanks to ministry of urban development’s (MoUD) '48,000 crore smart cities mission which would develop an area of a minimum size of 50 acres to 500 acres as smart localities or say pilots in 100 cities. To ensure time bound implementation and prevent cost escalation in smart cities projects, the government has brought in the concept of special purpose vehicle (SPV), to be registered under companies Act, having representation from urban local bodies (ULB), state government and private partners. The government’s strategy, however, is not foolproof. The programme faces teething troubles of raising resources and capacity building of municipal cadres. Moreover, it is mute on the lack of political representation and empowerment of ULBs.

First let us have a look at what and how urban residents are going to get benefited by the mission.

According to the smart cities mission guidelines released by prime minister Narendra Modi in June, these localities will act as “a light house” to other aspiring cities and areas within a city. For Jagan Shah, director, national institute of urban affairs (NIUA), a think tank of the MoUD, these localities would be a “demonstration” of sound planning and professional urban management and governance. The objective is to provide, the mission document says, “core infrastructure and give decent quality of life to its citizens, a clean and sustainable environment and application of smart solutions”.

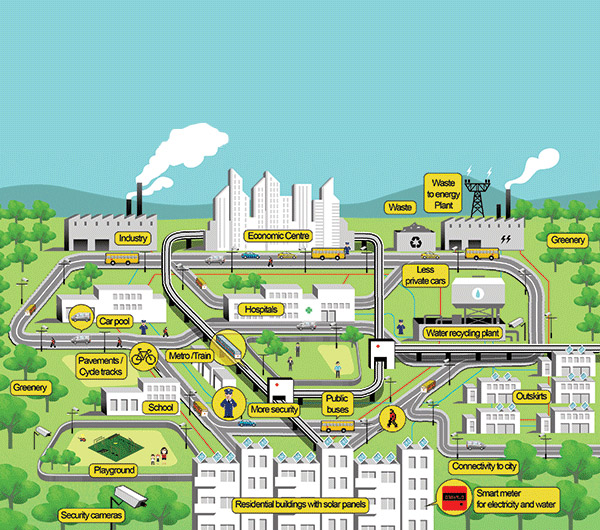

The mission provides for two strategies for development activities: area base development and pan city project. The area development, say the guidelines, can be done in three ways: retrofitting -- upgrading a city infrastructure in an area of minimum 500 acres; redevelopment -- replacing the existing infrastructure and new construction in minimum 50 acres; and Greenfield -- building an area of minimum 250 acres from scratch. Irrespective of the model, the area will have all basic civic amenities.

Interview: Sudhir Krishna, chairman, sectional committee under bis

The pan city project provides for use of technology in the existing city-wide infrastructure, intelligent transportation for example.

As per the guidelines, ULBs have asked city residents to choose the kind of area based development, location of the area and the project which can be taken up under pan city category. “It is interesting to note that the smart cities mission has placed people in centre of activity. People have to be consulted for making the smart city plan. One hopes the government will have an institutional arrangement to continue this engagement,” says M Ramachandran, an urban development expert and former urban development secretary.

All these work would be undertaken by the SPV. The ULB and state government, as written in the mission guidelines, will have equal equity shareholding in the SPV.

SPV for professional city management

Under the smart cities framework, the state governments and ULBs will have to delegate powers to the SPV to make it a single body to approve, execute and monitor projects related to the smart cities mission. It would also collect user charges, taxes and surcharges as authorised by the ULBs in the particular area.

The guidelines allow private companies to take equity share in the SPV, provided that the majority shareholding remains with the government (ULB and state government combined).

The board members will include representatives of ULB, state government and central government. While the CEO will be hired from the industry and the chairman of the board will be appointed by the state government.

“The chairperson of the SPV can be either the divisional commissioner, collector, municipal commissioner, or chief executive of urban development authority as decided by the state government,” says the mission guidelines. The staff would comprise of officials from ULB, state government and those hired from the market.

According to Karuna Gopal, founder, foundation for futuristic cities and advisor to MoUD, the SPV model will put an end to unilateral decision making. The CEO will have to take people in confidence. The governance will become more transparent, says Gopal. She says it is a good idea to hire professional experts from the market and buttress the existing system. Cities like Barcelona, Amsterdam and London have very well used SPVs for further development.

Experts also believe that the projects to be carried out under the mission would be approved keeping in mind financial viability and operational maintenance.

Until now India’s experience hasn’t been good in conceiving sound projects, says Shah of the NIUA. “Projects under JNNURM for example became stranded assets. The whole value chain was not thought through. Lack of efficient planning lead to cost escalation,” says Shah.

The projects have been designed in a manner that the rollout doesn’t take years and is done in a time bound manner, says Shah. The minimum size of 50 acre, 250 acre and 500 acre were finalised after extensive deliberations and possibility of completing the project, director of the MoUD think tank says.

The states have to submit their smart city proposal (SCP) by December 15. In the SCP, ULBs will not only have to propose projects but also ways of raising funds for financing those projects.

According to an MoUD official, the cost of smart cities work in a city might roughly come around '4,000 crore to '5,000 crore.

As per the decided allocation, the central government will provide '500 crore and a similar amount will be committed by the state government. Cities can also claim funds from related urban missions including Atal Mission for Rejuvenation for Urban Transformation (AMRUT), swachh bharat, housing for all, and Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana (HRIDAY).

ULBs can also consider issuing municipal bond, pooled finance mechanism, tax increment financing, borrowing from financial institutions, both domestic and abroad, and public-private partnership.

“The SCPs will be examined by teams of experts from India and abroad. The experts would include representation from NIUA and Bloomberg Philanthropy, the organisation is helping MoUD in short listing of cities competing for central government funding,” says the MoUD official.

The PM is likely to announce the first set of cities on January 26, he says. The remaining two sets of 40 cities would be approved in the subsequent years.

Where is political representation?

The proposed development of smart localities is a more incremental and pragmatic approach for upgrading the city infrastructure. Experts however believe the government has missed on larger structural problems dogging the urban development. The smart cities plan itself needs more detailing.

Rutul Joshi, assistant professor, faculty of planning, Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT) University, Ahmedabad, says that government’s focus is more on the means – the technology – and not the end, improving the civic life. The government doesn’t have a comprehensive agenda for reforming cities, says Joshi, stating that the structural issues haunting cities including planning, political autonomy, capacity building and cadastral map modernisation have been left untouched.

There are apprehensions about the power delegation and governance issues related to the SPV. The mission requires state governments and ULBs to delegate powers to the SPV. Given the precedence of lack of power devolution in case of 74th amendment Act, there are apprehensions if it would ever happen.

For Shailesh Pathak, executive director, Bhartiya Group, SPV will expedite the development work, which would make up for the poor devolution of power to the ULBs. He, however, disapproves of the upper hand of the state and not the ULB in the SPV. It is interesting to note here that the SPV chairman would be appointed by the state government. In most likelihood, the state government would appoint a divisional commissioner or a district magistrate for the given post, says Pathak. Mayor, a post defined in the constitution, has been kept away from the mission. This might lead to resistance between the elected representatives and SPV-state bureaucracy.

There is no political representation in the SPV, says Ramachandran. If an assertive local body with mayors and corporators choose to either positively or negatively influence the work of the SPV there are no ground rules which would help in dealing with such situations, he says.

Sudhir Krishna, chairman of standards committee on smart cities and a former UD secretary, says the SPV should be kept under the municipal corporation. The chairman should either be mayor or commissioner of the corporation. The smart cities work and projects to be overseen by the SPV should be well integrated with city’s master plan and overall city development.

One major challenge is going to be raising resources.

“At present municipalities finances are a mess. Getting them back on their feet is a big challenge. This would require overhauling the entire system of governance, disciplining expenses, budgeting, etc.,” says Pratap Padode, founder and director, smart cities council of India. Padode says that the ULBs will have to work on their project execution ability.

“Only then can they raise finances by way of bonds which would be necessary for project financing since all projects cannot run on grants alone,” says Padode.

According to Ramachandran, ULBs are not even ready for municipal bond. The credit rating has not happened for past seven years. Taking loans from financial institutions would take time as they have to do due diligence before giving their approval, he says.

“There is a debt limit for each state and also there is a limit to how much help can be taken from ADB or World Bank,” he adds.

Training of municipal cadre and staff to raise the in-house expertise is significant to the success of the urban projects. This is one reason why JNNURM has not been completely successful, he says.

The government should also formulate a fast track dispute resolution mechanism for smart cities project, says Padode. Many times the infrastructure projects are stuck as the concessionaire fails to deliver a project on time because the land or other resources have not been completely transferred.

India on a smart road

Smart cities mission

- Central support: Rs. 48,000 crore (Rs. 500 crore from centre per city)

- Target: 100 smart cities

- Features: Provide all basic civic amenities and smart solutions in a 50 to 500 acre area (minimum)

- Duration: Five years

- Nodal agency: Ministry of urban development (MoUD)

Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT)

- Central support: Rs. 43,000 crore

Target: 500 citiesFeatures: Ensure water supply and sanitation, pedestrian, non-motorised and public transport facilitiesDuration: Five yearsNodal agency: MoUD

Housing for all

- Central support: Rs. 1 lakh to Rs. 2.3 lakh per beneficiary depending on category defined

- Target: Two crore

- Feature: Slum rehabilitation, affordable housing for weaker section through credit linked subsidy, affordable housing in partnership with public and private sectors and subsidy for beneficiary-led individual house construction or enhancement.

- Duration: Seven years

- Nodal agency: Ministry of housing and urban poverty alleviation

Swachh Bharat Mission

- Central support: Rs. 14,623 crore

- Target: End open defecation, eradicate manual scavenging, devise modern and scientific municipal solid waste management across the country

- Duration: Four years (by October 2, 2019, the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi)

- Nodal agency: MoUD

Heritage City Development & Augmentation Yojana (HRIDAY)

- Central support: Rs. 453 crore

- Target: To focus on development of twelve heritage cities namely: Ajmer, Amravati, Amritsar, Badami, Dwarka, Gaya, Kanchipuram, Mathura, Puri, Varanasi, Velankanni and Warangal

- Features: Strategic and planned development of heritage cities, improvement in overall quality of life, focus on sanitation, security, tourism, heritage revitalisation and livelihoods retaining the city’s cultural identity

- Duration: Four years

- Nodal agency: MoUD