The underage Delhi rapist has walked free. Is he likely to be reformed when society’s mindset has not reformed?

Policemen line up the stretch of the lane from the Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg to the Feroz Shah Kotla cricket ground, where an India-South Africa Test is on. I turn to some policemen for the way to the reform home, also known as juvenile observation centre or bal sudhar grah, which is located somewhere behind the stadium. They are puzzled. As I try to explain my destination, one of them says, “Achchha, bachchon ki jail? Toh aisa bolo na (You mean children’s prison? You should say like that).”

When I tell Aarif Iqbal, in charge of the observation home, about the incident, he pauses for a moment and says, “See, this is where the problem lies. This is a problem of perception. We can call these children ‘juveniles in conflict with law’ and this place as ‘observation home’, and refrain from using words like ‘accused’, ‘convicts’ and ‘jail’. But little can change until society sees them as different from adults accused of crime.”

The observation home has a large compound, with large halls on three sides – and the whole campus is surrounded by high walls topped with barbed wire. Two boys in a blue uniform are sitting on a patch of land covered with soft green grass, warming themselves in the afternoon sun. In one of the halls, some 15 boys, all aged between 13 and 17, giggle on a joke that one of them has shared. Their voices echo and enliven the damp room. One of the boys, sent here for theft, shows a shirt he has been stitching for some days. He smiles and says, “I love this work so much. I will open my own tailoring shop once I am out of this place.”

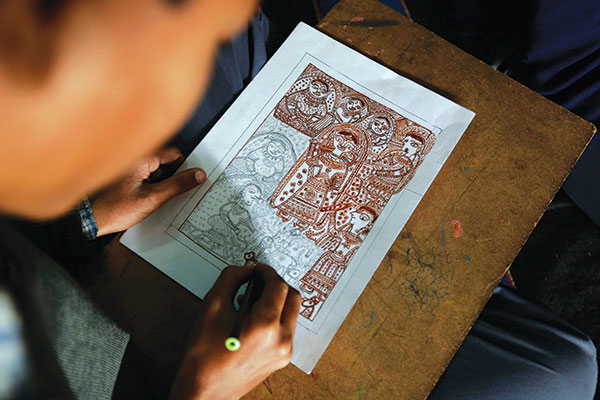

Displayed on the walls of the verandah are beautiful paintings. Confident strokes of paintbrush and use of bright colours reveal a hidden creative streak among these juveniles. In another hall, where they are given non-formal education with lessons in history and civics, the walls are decorated with embodied sarees and women’s wear, one piece with beautiful phulkari work on it. In two big halls a number of cots lie spread against a wall where a TV set has been anchored on a stand.

“Though people think this is a jail, we make all possible efforts to make it a home for these children,” says Iqbal.

Amid all this there are some grim faces too. These boys exude the same mellowed angst and pain that are often reflected on the faces of their more fortunate counterparts when they are sent to boarding schools: the pain of being away from their parents, living in the confines of four walls.

Mansoor has just turned 14. His pimpled face and a hint of hair on the upper lips speak of the child confused with new developments. His eyes are red with persistent rubbing, as he tries to conceal his tears and then breaks down. “I did nothing. It was a friend of mine who did it,” he says. Mansoor was sent here for forcing his friend into unnatural sex. His parents are bedridden, having met an accident a few months earlier. “I want to be with them, they need me. I never did anything,” he maintains.

Realisation of the gravity of the offence seems missing. The resentment looks more like a regret of flouting a rule, made by the parents and being grounded, than that of guilt for committing a crime.

Juvenile redemption

In the Hollywood classic ‘Shwashank Redemption’, when Red who has spent some 40 years in jail is asked if he is ready to return to society, he replies, “There’s not a day goes by I don’t feel regret. Not because I’m in here, because you think I should. I look back on the way I was then: a young, stupid kid who committed that terrible crime. I want to talk to him. I want to try to talk some sense to him, tell him the way things are. But I can’t. That kid’s long gone, and this old man is all that’s left. I got to live with that. Rehabilitated? It’s just a bullshit word.”

Though he was not a child when he committed the crime, he was a young man who did not foresee well the repercussions of his act. But his remarks bring to light the irony that the life in a prison can extinguish the remaining innocence in a young offender. This is one of the reasons why voluntary organisations and activists vehemently opposed the recent move to lower the cut-off age for the trial of the offender.

A majority of the people I spoke with on this issue felt that the crux of the debate on juvenile delinquency should be to understand the circumstances in which these children commit crimes and endeavours should be made to eradicate those circumstances.

Amod K Kanth, founder of the NGO Prayas, which works for child rights, says, “In most cases the juveniles in reality have not done what is attributed to them. In at least 30 percent cases they are innocent or the offence committed by them is not serious. They live in the circumstances where they are extremely vulnerable and are exposed to such conditions which compel them to commit offence. The share of IPC [Indian penal code] crimes registered against the juveniles in the total crimes is around one percent, which is very less compared to the countries like the US. It is projected as if so many children in conflict with law pose a serious threat to society, but the fact is that essentially we are a non-caring society. We do not care about our children.”

But do reform homes reform the juveniles, and do the underage have a chance to reform? Kanth says, “Through my experience at Prayas and through our initiative Yuva Connect (which helps children who come out of the observation home to make a fresh beginning), I can say that there is a negligible number of juveniles who are incorrigible.” He adds, “We have to ensure that after they leave the observation home they have to be made conscious that they are under some sort of supervision and for that we all have to make some efforts.”

Utsav Bains, a child right activist based in Chandigarh, says, “Our juvenile justice system is not at all effective to ensure justice. It’s indeed a failure in Punjab, Haryana and Chandigarh; it is under-resourced and neck deep in nepotism, the members of JJBs are generally selected on political affiliations or on their proximity to bureaucrats, which creates a scenario where members are hardly interested in the juveniles, delinquency or justice.”

He adds, “After reading what this juvenile did (in the Delhi gangrape case), people’s immediate reaction is that he should be hanged along with other rapists. But that would be a juvenile reaction. The bigger question we need to address is why a child would commit such a horrifying crime.”

According to Bains who has interviewed hundreds of delinquent juveniles, more than the child, it is the society which needs to reform. He asserts, “Children reveal a society’s soul. As long as you make children suffer violence, abuse, or even patriarchy, this is bound to happen.

Scientific research has proved that a majority of juveniles who commit acts of violence are themselves victims of violence. Gandhi understood this, that’s why during his final phase, he said, ‘If we are to teach real peace in this world, and if we are to carry on a real war against war, we shall have to begin with the children’.”

Circumstantial evidence

As I enter the office of Premoday Khakha, the superintendent of the ‘observation home’ for boys in Sewa Kutir Complex, at Mukherjee Nagar in south Delhi, he is discussing a case of a juvenile with the counsellor. The 16-year-old, class-10 student is accused of murdering a boy two years younger. His parents are apprehensive of getting a bail for him as they fear he might be harmed if he comes out of the home. On the other hand, the juvenile thinks that his parents are angry with him and do not want him back, which is adding to his restlessness and anxiety.

Khakha explains, “We have to understand the state of mind of the child. It is necessary to empathise with him and understand the circumstances which led him to commit an offence. They need a sense of protection, especially when they are sent to observation home and when they leave from here. Children need an assurance and protection from the society and above all a responsible guardianship is must.”

He adds, “We have to ensure that a system is created where society ensures that circumstances that propel these children to commit offences are eradicated and also those who go out of the observation homes get enough support from the society to start afresh. Regretfully, the government does not have programmes to ensure opportunity for development for the juveniles.”

While some say a miniscule number of juveniles show the tendency of repeating the offence, nevertheless they too emphasise that circumstances play an important role in shaping their delinquency and the fact that they should be given a chance to reform.

“I never say that there is 100 percent guarantee that they will reform. But then is it an excuse not to give them a chance to reform?” says Devendra Gupta, who serves as a legal aid counsel for the juveniles at the Feroze Shah Kotla facility.

Raju who is staying at the observation home at Feroz Shah Kotla wears an infectious smile. He has been sent here for theft. He comes from Rajgarh, Haryana, and is part of a gang of children committing petty offences, often under the guidance of family members. “We used to dress up well and go to wedding parties. There, we would drop a bowl of chutney or something else on ladies. When they would go to clean it up, we used to flee with their purses,” says Raju with a mischievous smile.

Asked if he will resume the old tricks once he is free, he says, “I will not do it. A lot of kids in my village do this as elders tell us that we are children and will not get any severe punishments but living far from home is the biggest punishment.”

The Juvenile Justice Act provides for institutional care for juveniles in conflict with law and children in need of care and protection up to the age of 18 years. However, most of the children in care have nowhere to go once they reach the age of 18 and are discharged from their institutions. “The fact remains that once they leave this place they are compelled to again live in the same circumstances which pushed them to the wrongdoings. As responsible citizens we have to ensure them a sense of protection. And that is the real challenge,” says Khakha.

Many provisions, lesser implementation

Section 43 of the Juvenile Justice Act states that a sponsorship programme may provide supplementary support to families, to children’s homes and to special homes to meet medical, nutritional, educational and other needs of the children with a view to improve their quality of life. It further adds, “The state government may make rules for the purposes of carrying out various schemes of sponsorship of children, such as individual to individual sponsorship, group sponsorship or community sponsorship.”

In consonance with this provision, the Integrated Child Protection Scheme (ICPS) was proposed in 2006 and implemented in 2009. The idea behind the scheme was to ensure the safety of children, with emphasis on children in need of care and protection, juveniles in conflict with the law and other vulnerable children. But the state machinery seems to have almost discarded the scheme. A senior official working on juvenile justice admits that it is not taken seriously. “When I was in charge of the scheme, I established four ‘district child protection offices’ as I felt it was a good way to check delinquency among the juveniles. But sadly no visible development took place after that.”

The way we see them

Another officer in charge of a juvenile home in Delhi makes an important point. “We are instructed to give some vocational training to the children. But till we give them some certificate of training how will they be able to get any work on basis of that?” In that case, why can’t a juvenile home itself issue a certificate? “Do you think anyone will give them a job when they show a certificate issued by a reform home which most of us think is a prison?”

Another senior official working at a reform home in Delhi says, “The way they are treated from the very onset tags them as criminals. They are arrested and produced before the JJB which is by definition a board but in all respect looks like a court. The day a juvenile is arrested and brought to board he knows he is facing a trial. By the time they are sent to reform homes they know that people see them as criminals. No matter what we call them – ‘juveniles in conflict with law’ or ‘offenders’, till the juvenile system is reshaped to make them feel different from a criminal you can hardly help them.”

Insensitive policing

Monu, 19, stands outside the observation home in Sewa Kutir Complex along with his mother, sister and an ailing grandmother who can barely walk. He lost his right hand a year ago in an accident and his father is bedridden. His younger brother was arrested on December 7 from Sadar Bazar in a case of theft and is now in the observation home. According to the Juvenile Justice Act, 2000, a petty crime does not merit an FIR and arrest, and a daily diary report is sufficient. However, the lack of sensitivity among police officials often leads the juvenile to face a trial when it is not required.

Ray of hope

In 2005 Mazhar was living with his parents and sister in Sundar Nagar, Delhi, when during a fight with another teenager neighbour, he lost his temper and killed him. The 14-year-old was charged with murder along with three other boys and sent to the observation centre. A year later, he left and completed his education. Today he works in a garment factory in Gandhinagar. He says, “I very well know that it was a huge mistake and all through my life, I will regret it. But then I have tried to move on.” Now he earns around '19,000 per month. As for what happened to those three boys, he takes no time to reply. “I severed my ties with them when I left the observation home.”

Most of the people who work with the juvenile delinquents strongly believe that reforming them is possible and only requires an extra effort.

Gyanvati who teaches at an observation centre, recalls a boy, Rahul, who had committed a rape. “He is now free, but he still calls me once in a while. I came to know that he is studying and also teaching around 15 students of his locality to meet the expenses of his studies. I am sure he will do good in life.” she says.

Reforming ‘homes’

Government-run observation homes often face serious complaints of abuse. In 2008, the Delhi high court had mandated a “supervision committee for observation homes” to which complaints or feedback by parents of juveniles can be referred to. The committee is now non-functional.

Bharti Ali, co-director of the Centre for Child Rights and member of the supervision committee at the Feroz Shah Kotla observation home, says that the director of the department of women and child development is meant to oversee the functioning of the committee but there is little interest shown by the department. Ali adds that the reason behind this might be that there is another monitoring committee appointed by the high court which is functioning and there is no use of multiple committees.

In 2013 a committee formed under the directions of the apex court was to monitor the homes for delinquents across the country. It’s functioning is not transparent as reports of children’s abuse continue to come out of the juveniles homes.

Kant admits that some reform homes have problems. “But then that is the problem with the institution. We have to put in place a better institutional mechanism,” he says.

shishir@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the January 01-15, 2016, issue)