Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) is a concept aimed at providing a cash incentive directly to the intended beneficiaries upon fulfilling certain predetermined conditions. It originated in Latin American countries where the demand for social services by poorer households had drastically declined in the 1990s (UNDP, 2009). The scheme provided a shift from focusing on the supply-side to a demand-driven approach. A demand-driven approach would in principle help the government to effectively utilise its resources through catering to the needs of the targeted population.

The approach became a popular intervention strategy, with India starting CCT-based schemes for women and child development with the policy intent of (a) to induce behaviour change among beneficiaries, or (b) to increase demand for public services. Some of the examples are seen in areas such as improving maternal and child health, promoting birth of girl children and improving educational attainment among girls. These schemes are designed to incentivise gender equality and opportunity and increase the consumption of educational and health services.

The significance of CCTs in the domain of public health, especially to improve maternal and child health outcomes, is the focus of learning for at least two reasons. First, as a key indicator of public health, maternal mortality and child malnutrition feature as a top priority for the government and is high on the public policy agenda. One of the most recent steps in this regard has been the setting up of a task force to examine matters pertaining to the age of motherhood, imperatives of lowering MMR, and improvement of nutritional levels. [See https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=1629832] Second, the causes of maternal mortality and associated health issues in mothers and children are well established and understood. A large number of these deaths and causes of morbidity are preventable or treatable and present an opportunity to meet policy goals on a number of associated targets such as improving educational outcomes or securing livelihoods.

Key benefits under MMRY

Under Mukhya Mantri Rajshree Yojana (MMRY), girl child born on or after 1 June 2016 in the state is eligible and entitled for a sum of INR 50,000 in six installments. The sum will be transferred to the mother’s, or in her absence the father’s, bank account on fulfilling the following conditions:

- INR 2,500 on having an institutional delivery of a girl child

- INR 2,500 when the girl child completes 1 year with all vaccinations

- INR 4,000 on admission to 1st standard in any government school

- INR 5,000 on admission to 6th standard in any government school

- INR 11,000 on admission to 10th standard in any government school

- INR 25,000 on completing 12th standard from any government school

Source: http://wcd.rajasthan.gov.in/docs/Rajshri%20_Yojana.pdf

Issues of coverage in implementing CCTs for maternal and child health

It is important to note that CCTs are only part solutions that cannot make up for poor service delivery or outreach and might not be successful in situations involving acute supply-side constraints (UNDP, 2009). Dependence on the availability and accessibility of public services is a huge factor in the success of a CCT. Taking into account India’s service delivery structure, a large section of the intended beneficiaries may be left out of such schemes due to reasons such as poor or inaccessible services and a number of administrative challenges as we discuss below.

An assessment of Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), a CCT scheme aimed at promoting institutional deliveries in the country, highlighted many such challenges that still remain in improving healthcare infrastructure and delivery of services. While the scheme has had a beneficial impact on antenatal care, neonatal deaths, and institutional births, it is also documented that the poorest and the least-educated women had the lowest odds for enrollment (Jacob, 2011).

A review of existing cash-transfer programs in India by J-PAL (JPAL, 2018) found a number of challenges present, most importantly the lack of rigorous evaluations of such schemes in the first place. It was found that beneficiaries of most such schemes witnessed a significant delay in receiving their instalments, owing mainly to delays in administrative process as multiple steps are involved between the frontline worker completing the paperwork and the actual transfer of the instalment. Moreover, such schemes also rely on the banking system to transfer the benefits. While financial coverage in the country has been reported to be on the rise, people living in the remotest parts of the country still face issues of access and financial illiteracy. Some estimates such as the one made by Standard & Poor’s Financial Services survey in 2014 suggest only 24 percent of the adults in India to be financially literate; India reportedly hosts the second largest unbanked population in the world after China (Draboo, 2020).

Hence the number and type of conditions placed in a scheme need to be carefully evaluated with respect to the service availability, ease of monitoring, and compliance verification as it can hamper the smooth implementation of the scheme.

Situational constraints in field implementation – Case of Mukhya Mantri Rajshree Yojana

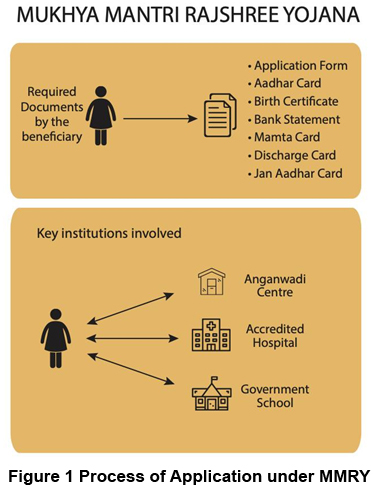

The Mukhya Mantri Rajshree Yojana (MMRY) is a Rajasthan state-sponsored CCT scheme to promote survival and education of the girl child. It includes cash incentives for the beneficiary upon meeting some eligibility criteria and applying through public institutions such as: anganwadi, government school, or a hospital (see Figure 1). Easy accessibility of these institutions and efficient service delivery on their part are prerequisites to avail scheme benefits. Also seen in the figure are the different documents a beneficiary is required to present during the course of the availing benefit from the scheme.

While the application process follows a sequential set of conditions, various challenges are bound to arise at every step. As part of a capacity-building project being run in Rajasthan, we have learned that: inability in procuring the birth certificate on time, having incorrect details on the documents, or the unavailability of ANM/ hospital staff to provide and verify the documents can result in severe delays in receiving the instalments or not receiving any benefits at all. Apart from this, paperwork and administrative delays by government officials can add on to the time taken when the beneficiary finally receives her share of the installment. Such administrative issues are a common occurrence in government systems, but the cumbersome and delayed redressal mechanisms further add to the misery of the beneficiaries. An audit report conducted by the Comptroller and Auditor General confirms such administrative challenges and reports that 16.99 percent of the applicants between June 2016 and March 2018 did not receive financial assistance due to non-availability of passbook or domicile of the applicant from another State.[See https://cag.gov.in/sites/default/files/audit_report_files/Chapter_3_Compliance_Audit_of_Report_No_4_of_2019_General_and_Social_Sector_Government_of_Rajasthan.pdf]

Working closely with the eligible women beneficiaries has shown how the success of such schemes depends heavily on the efficiency of various institutions and how any weak institutional link can disrupt effective delivery of services. Group discussions and public consultations conducted around the access challenges of the scheme have shown that a common issue voiced by rural women is the lack of information provided regarding ANM visits at the anganwadi. This can directly result in delays or failure in getting their children vaccinated on time, which further disrupts the conditions necessary for availing various benefits. In another example, a woman was unable to avail the scheme benefits as her daughter was delivered in the ambulance on her way to a hospital, thus making her ineligible for the any benefits under the scheme.

Developing champions of improved health services

Collective action through community participation for rural development can be seen as a strong tool to improve public sector accountability as well as the quality of public service delivery (Gine, et al., 2018). For issues pertaining to women and children in particular, women’s participation becomes crucial. We understand that women’s decision-making power within and outside their households is highly constrained as we go deeper into rural areas. In addition, their education levels also remain low, which limits their ability to access information and engage with the society as well as with government/service providers.

Engaging women in groups can be an effective method of increasing their participation in the social sphere including local governance and public service delivery. When such instituted women members meet regularly and get involved in activities together, it helps build social capital that is dependent on trust, social norms, and networks (Saha, et al., 2013). Women individually might not have enough say or knowledge about the governance processes, but in a group they are better placed to be heard and make an impact in their society. Success of self-help groups (SHGs) in India is a prime example of this growing social capital and its effect on improving rural livelihoods. Forming such women’s collectives can help in easy dissemination of schemes-related information among larger groups of women, and together they stand at a position to question, to demand, and to effectively communicate with government officials and in turn ensure effective service delivery.

In 2018, India Development and Relief Fund (IDRF) and S M Sehgal Foundation (SMSF) collaborated to fund and implement a women’s group-based intervention to overcome situational constraints in the delivery of schemes targeted at women and child development.

The project is designed in two phases: In the first phase, the identified beneficiaries are constituted into mahila sangathans/women groups, followed by being trained on select schemes. Capacity building of the participants in formulating a women’s group, devising their objectives and plan of action, forms a part of this phase. An outcome of this part of the project is to bring about positive behaviour change toward availing and benefitting from maternal benefits under the MMRY as well as nutrition and health-related interventions conducted at the anganwadi centre in their village.

The second phase of the project looks at advancing the purpose of the women groups beyond awareness generation and toward collaborating with district officials on effective implementation of select schemes. In this phase, interface sessions and consultation events are conducted with local government officials and participating mahila sangathan members to provide the stakeholders a platform for dialogue. Such an opportunity can help in not only overcoming the administrative barriers to availing the scheme but also has the potential to amplify social accountability in the relationship between the government and the citizens.

A women-led, rights-based approach has the potential to address a critical gap in the functioning of reproductive and child health service delivery. First, as consumers of these services, it is in their (women’s) best interest to monitor and report any faults or gaps in delivery mechanisms. Second, an empowered and aware women’s group is best suited to negotiate compliance. Lastly, a strong accountability feature of this approach is to generate feedback for continuous improvement and learning.

A key policy learning from this discussion is the need to develop and harness women groups as powerful change agents in improving access to quality health delivery systems for reproductive and child health. Civil society members can usefully employ this potential of women’s groups through women’s collectives to build and develop social capital among this marginalised group in the society. This can further pave way for women to participate in their local governance and improve social accountability in the running of schemes meant for their health and that of their children.

References:

1. UNDP, India. 2009. Discussion Paper on Conditional Cash Transfer Schemes for Alleviating Human Poverty: Relevance for India.

2. Jacob, K.S. 2011. Conditional Cash Transfers and Health. The Hindu. Accessed on July 20, 2020. Available at https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/conditional-cash-transfers-and-health/article2145126.ece.

3. JPAL. 2018. The Role of Cash Transfer in Improving Child Health: A Review of the Evidence. J-PAL South Asia at IFMR. Accessed on July 20, 2020. Available at https://www.povertyactionlab.org/sites/default/files/review-paper/CaTCH_review-paper_cash-transfers_2018.10.09.pdf.

4. Gine, X., Khalid, S., & Mansuri, G. (2018). The Impact of Social Mobilization on Health Service Delivery and Health Outcomes. Policy Research Working Paper 8313. World Bank Group.

5. Draboo, Shailla. (2020). Financial Inclusion and Digital India: A Critical Assessment. Economic and Political Weekly. ISSN: 2349-8846. Accessed from https://www.epw.in/node/156845/pdf . Accessed on 9.6.2020

6. Saha, S., Annear, P., & Pathak, S. (2013). The effect of Self-Help Groups on access to maternal health services: evidence from rural India. International Journal for Equity in Health. 12:36.

Sood (s.sood@smsfoundation.org) is a social scientist, working with Development Research and Policy Initiatives at S M Sehgal Foundation. Sharma is a research associate with Development Research and Policy Initiatives at S M Sehgal Foundation. (v.sharma@smsfoundation.org)