Universal Basic Income: The mother of all welfare schemes. Modi's next surgical strike?

From Mahatma Gandhi’s Sabarmati Ashram to corporate talkshop Davos, it’s creating a buzz everywhere. If nothing is stronger than an idea whose time has come, then people in more and more countries are likely to start getting free pay cheques every month from governments. It’s called universal basic income (UBI) – an old notion of state welfare that has been rediscovered in the increasingly anxious West to counter joblessness and automation. After a failed start with a Swiss referendum last year (result: no), several European counties are starting pilot projects to deliver to all citizens a nominal amount of money not tied to any conditions or any health or pension scheme. Just plain free money.

READ: How basic should basic income be?

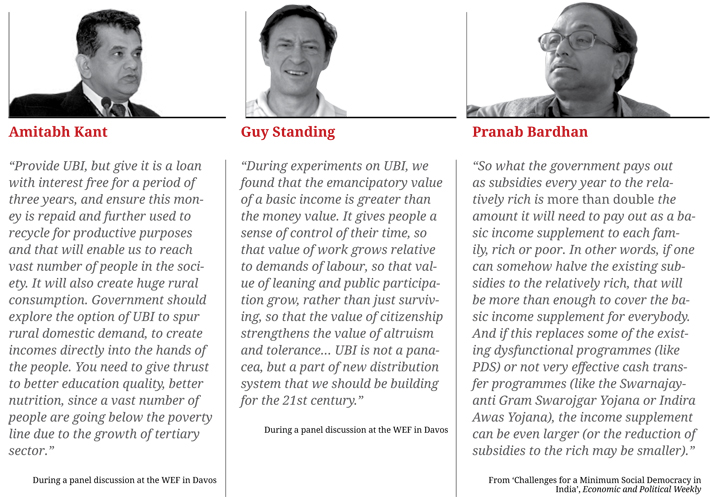

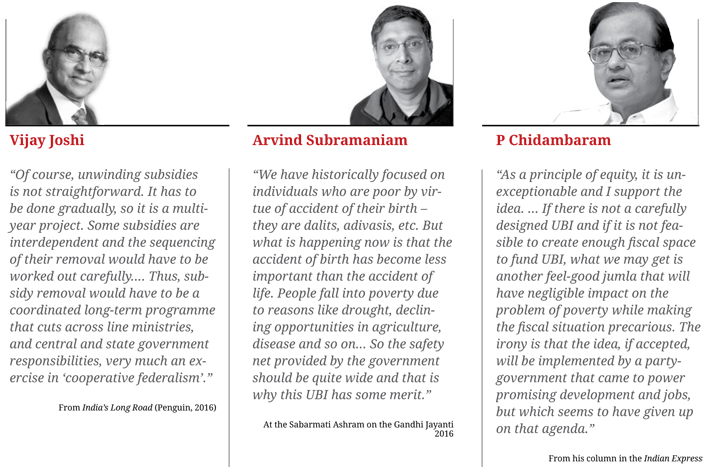

In India too, for different reasons, the idea has arrived. Arvind Subramanian, a reputed economist and chief economic advisor to the finance ministry, has promised to devote a chapter to UBI in the Economic Survey this year. Subramanian is enthusiastic about UBI. At the Gandhi Jayanti celebrations at the ashram last year, he held an imaginary dialogue with the Mahatma. “What would Gandhiji have said to this idea of UBI?” he asked, listing out at least four objections he would have – charity to able-bodied persons, cost to the government, market forces ranged against the poor, and men misusing the money on vices. Subramanian then went on to answer Gandhiji. “Today there are at least 1,000 schemes that the central government runs for the poor… It is not clear that the money actually reaches the poor. So the question is whether the UBI is a more effective way of reaching the poor,” the Indian Express quotes him as saying.

READ: “J&K could be an experimental ground for UBI”

Gandhiji, though, may not have any objections. Sarath Davala, Renana Jhabvala, Soumya Kapoor Mehta and Guy Standing, in their book Basic Income: A Transformative Policy for India (Bloomsbury, 2015), cite Gandhiji’s famous ‘talisman’ quote, and then say, “A basic income, properly implemented and backed by the presence of a Voice organisation that can defend ‘the weakest’, can give real effect to the hopes that Gandhi had in mind.”

READ: Pilot projects in some villages of Madhya Pradesh found UBI making a big difference

At Davos, meanwhile, the World Economic Forum meeting in January this year devoted a panel discussion to basic income. Guy Standing, professor of development studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, and a co-president of the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN), one of the tireless pioneering advocates of the idea in our times – gave three justifications for the apparently counterintuitive concept:

“The first is that it is a means of social justice. It goes back to those thinkers who said public wealth is created over generations and any of us should know or should have the humility to know that our wealth is due to the contributions of previous generations and much more than you and I do ourselves.

READ: Basic income should have maximum inclusion: Renana Jhabvala, SEWA Bharat

“The second reason, it is a means to enhance republican freedom. Republican freedom is different from standard liberal form of freedom, in the sense that it means freedom from domination by figures of authority using their arbitrary power. It is a mechanism to enhance republican freedom.

“Thirdly, it is a means of providing people basic security. In that regard, it is not for eradicating poverty per se. It is for handling the issue of insecurity.”

Then, it’s high time we familiarised ourselves with the debate of our times.

READ: Universal Basic Income an alternative to state subsidies: Economic Survey

What is universal basic income?

In theory, the state pays a fixed amount to people, no questions asked. It is periodic, not one time. It is in cash, not in the form of goods (like PDS) or services (like healthcare). It is paid to individuals, not to groups, though it could be a household or family too. It is universal, not targeted at only the poor. It is unconditional: the beneficiary does not have to satisfy some condition in order to be eligible. Everybody gets it.

Where did this idea come from?

It’s a long story. Many European philosophers have spoken about it over the centuries, from Thomas More of the Utopia fame to Thomas Paine (Rights of Man). In this century, Erich Fromm favoured this notion, because it would grant us freedom from the most fundamental worry – of not having any money. He wrote, “A guaranteed income, which becomes possible in the era of economic abundance, could for the first time free man from the threat of starvation, and thus make him truly free and independent from any economic threat. ... People would learn to be no longer afraid, if they did not have to fear hunger. (This holds true, of course, only if there is also no political threat that inhibits man’s free thought, speech, and action.)”

In the rather recent past, the idea has been proposed by economists of international repute, especially Pranab Bardhan of University of California at Berkeley and Vijay Joshi of Oxford.

Why universal? What could be gained by doling out money to one and all, including the super-rich?

It need not be universal. With a population upwards of 1.2 billion, India will have to consider some or the other cut-off. However, UBI supporters believe that any cut-off will lead to controversies over selection criteria and will raise all the debates we have seen over the poverty line. Giving free money to one and all solves the problem of beneficiary selection. Also, in any case, all money, including what is paid to the super-rich, will ultimately come back into the system, pushing demand.

Has it been done anywhere?

Switzerland had a headline-making referendum in June last year, and people rejected the idea. It made news, as people were effectively saying ‘we are not robots’ and there is dignity in earning by work. However, pilot projects are on in Finland, the Netherlands, and elsewhere. In India, SEWA Bharat, along with Unicef, did a pilot in Madhya Pradesh in 2011-12, with heart-warming outcomes (see ground report in following pages).

Is it feasible at all for India? Where would so much money come from?

Yes, arguably. Bardhan and Joshi say that a respectable amount can be handed out to all citizens or to most (counting out the really rich – as in the Give it Up campaign in case of LPG subsidy), if a plethora of subsidies are withdrawn. There are hidden subsidies, non-merit subsidies, subsidies benefiting all (think of railway fares), which can be done away with. That would free up a humungous amount – far more than what is needed for a basic income. There are other ways to finance the scheme too, for example, by encashing public sector resources.

With varying figures for basic income, there are varying scenarios presented by different economists but with the same logic. Joshi’s case goes thus: If the universal basic income is Rs 17,500 a year per household (five members), it would cost 3.5 percent of GDP. Now, look at subsidies. A 2003 study by the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) found that ‘non-merit subsidies’ were 7.7 percent in 1998-99 and a latest, ongoing study is tipped to indicate that subsidies in 2014-15 are “of the same order of magnitude” (the study is yet to come out, and Jean Dreze argues the figure is likely to come down). In any case, the 7.7 percent of GDP is going to non-merit subsidies, which excludes merit subsidies, meaning schemes relating to education, health, nutrition, environment, rural development, roads and bridges and urban development. So stop all non-merit subsidies and have enough funds to give basic income to all and yet some money will be left. Joshi also adds several other options for generating funds: implicit subsidies in the form of ‘tax expenditures’, PSE privatisation and taxing agricultural income among others.

Will it then hurt the PDS? And is this an extension of cash in lieu of PDS?

Some of the advocates of UBI have no love lost for PDS, though they carefully point out that there is no need to touch the core merit subsidies like the ones going to PDS, health and education.

On the other hand, those championing PDS (Dreze, to name one) have flagged the dangers of messing with PDS and other welfare schemes to fund basic income.

It looks like a win-win formula. Isn’t there any fine print, any criticism?

It is almost win-win, yes, that is why it is often said that this is one concept that has support from both the left and the right around the world. However, opposing voices too are coming from both the left and the right, as the UBI has become a hot topic in the west in the past year, what with job recession and automation. The Economist magazine, not a great votary of social welfare, calls UBI “an answer to a problem that has not materialised yet”.

In India, unlike in the west, the UBI is proposed not for social security against joblessness but as a basic welfare measure. But the big problem area will be its financing. Any subsidy withdrawal will have to be fully debated and carefully implemented. Otherwise, UBI can be a Trojan horse to undercut the welfare state. Simply put, the Indian story so far has been that the state runs hundreds of schemes for the poor and provides hundreds of goods and services to the poor but there are vast leakages and money is wasted. So the UBI argument is to bunch together all that money and give to the needy directly. No wastages. But, crucially, this means no answerability of the state too. With basic income in hand, the poor will be left to market forces (in some sectors). Hypothetically speaking, it’s like the difference between offering people free treatment at a government hospital (however badly run and inefficiently managed but somewhere within the state apparatus) and giving money to the poor to get treated at any private hospital (however high the charges may be).

In short, UBI has to be the way to expand the welfare state to counter growing inequality, and not a way to tinker and truncate the welfare state.

The government, it appears, is in two minds. Subramanian is gung-ho about UBI, and the Economic Survey will formally inaugurate the UBI debate. However, at Niti Aayog, deputy chief Arvind Panagariya is not convinced. In an interview to the Indian Express, he has said that the state simply does not have enough money to finance such a scheme. (Curiously, in a blurb for Davala and others’ book ‘Basic Income’ based on the SEWA project, he had this to say: “If you want to help the poor along all dimensions – education, health, financial inclusion, basic amenities and even asset creation – put additional money in their hands with no conditions attached. This is the simple but powerful message of this pioneering study.”)

Niti Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant too said at the WEF in Davos in January that he would prefer basic income in the form of interest-free loan (which, then, is not basic income at all).

“If you were to do away with the rural employment scheme and PDS which are inefficient, it is better to pay directly to the individual accounts rather than going through any middleman,” he said at Davos. “However, having said that, I am a great believer in not giving money as grant. Provide UBI, but give it as a loan with interest free for a period of three years and ensure this money is repaid and further used to recycle for productive purposes and that will enable us to reach a vast number of people in the society.”

A full-scale UBI will need infrastructure on the ground too. Particularly, as with the SEWA Bharat project in Madhya Pradesh, the beneficiaries must have bank accounts and they must be seeded with Aadhaar. There, in spite of the success of the Jan-Dhan Yojana, a lot more remains to be done yet. By January 11, a total of 26.69 crore Jan-Dhan accounts have been opened, and only 15.36 crore of them have been Aadhaar-seeded. Thus, as of now, a substantial number of people are without bank accounts, and a substantial number of existing bank accounts are without Aadhaar link. Like the launch of DBT without enough bank accounts, UBI can be a hasty revolution today.

Now, one can only wish it has better planning and execution than demonetisation, especially since it does not need secrecy.

Will the budget announce this mother of all freebies?

For prime minister Narendra Modi, UBI makes ample sense. It is the logical next step after direct benefit transfer (DBT) – a UPA initiative he has wholeheartedly taken forward. UBI beautifully falls in place with Modi’s much-talked-about JAM trinity of Jan-Dhan, Aadhaar and the mobile number – as if all the steps so far were taken with this destination in mind. Given his economic philosophy, UBI provides a good excuse to cut non-performing subsidies. Moreover, like his new-year eve announcement of maternity benefits to sooth demonetisation backlash, he can simply rename an existing scheme or club some of them together under a new name and, presto, you have the UBI overnight. A UBI-like schemes need to be universal and pan-Indian. It can be tried out in some select districts, as with DBT in January 2013, and then scaled up.

More importantly, at this juncture UBI makes maximum sense for two reasons: after the strong dose of demonetisation, UBI can not only be a sweetener to wash away the bitter aftertaste, it can also provide a post-facto rationale in popular perception. (Indeed, the UBI idea was floated seriously only when some commentators thought some black money won’t return in the system, and the government will have extra money on hand.

Also, remember one of the 2014 campaign promises? Modi talked of how a certain amount can be deposited in everybody’s bank accounts if black money is repatriated from abroad. Later, an embarrassed BJP chief Amit Shah tried to call it just a jumla, just an expression. UBI can very well be positioned as making good on that promise, no matter how small an amount it may be. This ties up with his newfound focus on the poor and the Garibi-Hatao plank – yet another instance of Modi as the second coming of Indira Gandhi. Free cash in your account, no questions asked, is unprecedented in India. He can go one up on Indira after that. The poor will gratefully remember his gesture, if not for generations, then at least till 2019.

The second reason is, of course, Uttar Pradesh.

ashishm@governancenow.com

(The article appears in the February 1-15, 2017 issue)