The demographic dividend can be a boon if the workforce is given productive jobs. Otherwise, India must prepare for social unrest

East Asia went through an economic miracle between 1960 and 1990, with income per capita nearly tripling. The four Asian Tigers – Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea – achieved impressive growth rates of more than 7% for more than three decades. Japan went through a similar phase till the 1980s.

This prolonged period of economic growth is attributed to export-oriented policies, investment in health and education, high savings rate and capital accumulation. Studies have examined the influence of demographic transition on economic growth [Bloom and Williamson: 1998]. If most of a nation’s population falls within the working ages (15-60), the productivity of this group can produce a ‘demographic dividend’ of economic growth, assuming that policies to take advantage of this are in place. The combined effect of a large working-age population and health, family, labour, financial, and human capital policies can create virtuous cycles of wealth creation.

India faced a similar scenario with fertility rate declining in the 1980s leading us to today; where we are one of the youngest populations in the world and the largest workforce on the planet at the exact time China’s labour force begins to decline. India currently has 120 crore people with a median age of 26 years. By 2030, India is projected to have 1.4 billion people, of which over 100 crore will be in the age group 15-64 (productive workforce).

This is a boon as well as a challenge. To consider the scale of the challenge, the working-age population, aged between 15 and 64, will rise by 12.5 crore in the current decade, and by a further 10 crore in the following decade. A third of this growth will come from poorer and less literate states, particularly Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (Literacy: 69.8% and 69.7%; GDP per capita: 31k and 37k respectively in 2014). To employ this population, India needs to create 10 crore net new jobs in the next 10 years. From 2002 to 2012, China created 13 crore net new jobs in services. However, in India, no net new jobs were created during 2005-10.

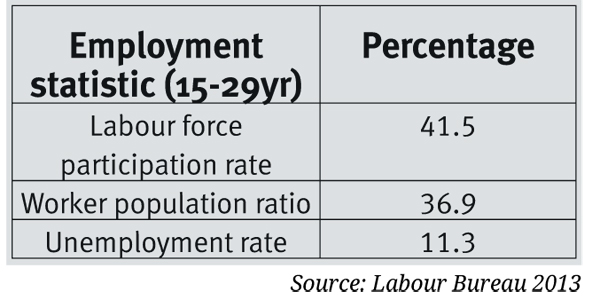

India’s youth unemployment rate currently stands at 12.9% compared to an overall 4.9% unemployment rate across the country. Overall rates of unemployment in developing countries are generally lower than observed in developed economies because most individuals cannot support themselves and their families through social protection schemes.

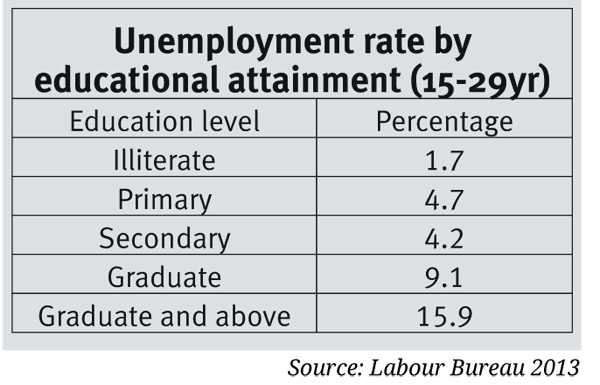

According to a National Employability Report, 2013, almost half the graduates are unemployable in the market, while according to labour ministry statistics, almost one in three graduates up to the age of 29 is unemployed. The Economist estimates that each year India produces double the number of graduates it can absorb.

The problem lies not just in the quantity of jobs. India’s incomplete economic liberalisation since 1991 has left the country with few good employment opportunities for unskilled workers who do not have much education. Statistics verify what is plain to see; all cities have an army of liftmen, guards, peons and delivery boys. About 85% of the jobs are in the informal sector, another 11% are casual jobs with formal companies. IT firms account for only a few tens of lakhs of jobs out of a total of about 50 crore. Twenty-three per cent of Indian workers are categorised as working in ‘industry’, compared to nearly 30% in China and 22% in Indonesia. However, half of India’s industrial workers are in construction. In India, manufacturing does not involve exposure to modern machinery, techniques; more than half in this sector works in facilities without electricity.

The skills mismatch in the youth labour markets has become a persistent and growing trend. Over-education and over-skilling coexist with under-education and under-skilling and increasingly with skills erosion brought about by long-term unemployment. There hasn’t been much growth in manufacturing to create low-skilled jobs. Young men often have no choice but to stay in low-paying idle jobs. This is a result of supply-driven education and a lack of interface between the various stakeholders – industry, education institutions, and education and labour ministries.

Our leaders have long said they are committed to generating employment, but have shown little stomach for the economic upheaval that rapid job creation entails. China’s policymakers accepted that the process of adding jobs overall often destroyed jobs in particular industries and places. Politicians have preferred economic palliatives such as NREGA and subsidies. The lack of political resolve means India is unlikely to summon up the single-minded dedication with which South Korea, Taiwan and China created industrial jobs. India’s demographic dividend will yield only a fraction of what it could, and the problem of low-quality employment will continue.

In the rural areas, majority of the population is engaged in the primary sector, resulting in low productivity and persistent poverty. There is also a need to increase formal employment, which currently constitutes only 8% of the labour force.

Impact of unemployment

How is this going to affect India? Hundreds of millions of young people are, or soon will be, looking for jobs and spouses. If those hopes aren’t fulfilled, aspirations will turn into frustration. And, frustration can manifest itself in rising crime. Long-term youth unemployment drains the motivation and ambition of those it afflicts and makes them more cynical. This is evident all around the world, including developed economies. Unable to become part of the rising middle class in India, this rising army of the unemployed could fuel violence and destructive politics, thereby destabilising the country. It can result in a vicious circle of inter-generational poverty, social exclusion and trigger violence.

Does the frustration of India’s youth help explain the prevalence of sexual harassment and violence against women? India already fares badly in terms of the demographic divide between males and females with 933 women for every 1,000 men. This number looks even direr with the youth sex ratio standing at 908, and adolescent (10-19) sex ratio at 898. Certainly, the patriarchal society and other reasons play a part, but it is worth exploring the role of economic and social frustration. Women in India describe daily incidents of harassment: taunts, stalking and groping. Most of the time, the culprits are relatively young men with lots of time on their hands and nothing productive to do.

The Justice Verma committee report speaks of the “mass of young, prospect-less men whose sexual harassment of women may tip over into more aggravated assault. These men are fighting for space in an economy that offers mainly casual work”. The committee’s report concludes that “large-scale disempowerment of urban men is lending intensity to a pre-existing culture of sexual violence”.

Craig Jeffrey, professor of development geography at Oxford University and an expert on India’s unemployed youth, has given academic currency to the Indian the act of loafing about with nothing to do: “timepass”. “Rapid social change in provincial India has created a vast army of educated and semi-educated ‘loafers’ among young men. Young men find themselves with little or no opportunities or resources and find it difficult to get married. They hang about near college campuses or even by the roadside, taking out their frustration on women. ‘Time-passers’ aren’t just unemployed or underemployed; they’re often also unattached. After decades of skewed sex ratios at birth, India now has approximately 37 million more men than women. This excess supply of men, combined with falling fertility rates has led to a ‘marriage squeeze’.” [Craig Jeffery: 2010]

The combination of young men with few prospects and the frustration of being single is especially pronounced in some northern Indian states, where sex ratios are the most skewed. Sexual harassment is just one of the social pathologies that can arise from these economic and demographic trends.

Insurgency, also related to the challenges of youth unemployment and underemployment [Magioncalda: 2010], is another major worry. Regions with inadequate employment opportunities have witnessed serious problems. Similarly, the Arab Spring, the London riots of 2011 and the Occupy Wall Street movements were to an extent an expression of the disenchantment and the lack of opportunity for youth in those countries. It does not take much for such small-scale movements to become huge destabilising forces.

India may soon discover that its demographic dividend has its perils.

Roy is a fellow at Pahle India Foundation