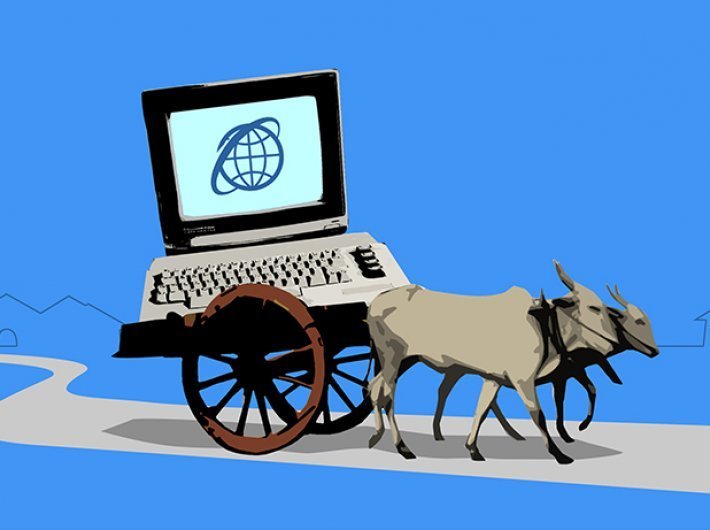

The pandemic has underlined the need to reduce inequalities in internet access. A public-private partnership can show the way

There has been an active debate globally and in India about the digital divide. This debate has gained additional weight during the Covid-19 pandemic because the acceleration of the need for digital access to health and other social services has thrown this issue into sharper relief. A critical public policy challenge which arises from the digital divide, when the private and public sectors are both necessary but neither sufficient by itself, is how to design an effective public-private partnership (PPP) model as a bridge across the digital divide. This article attempts to answer that question and also why a well-designed PPP bridge across the digital divide can reset the debate on responsible digital conduct between states and technology companies.

One of the major preconditions to the design of an effective PPP bridge across the digital divide is to have three key building blocks of private sector digital prowess, public sector digital bridging instruments and payoffs from the PPP bridging of a substantial digital divide.

India is often accused of missing the bus in terms of economic liberalisation and globalisation. However, this cannot be said of the digital revolution. India’s early leadership and prowess as a world-class information technology services centre with global reach was exemplified by private sector companies like TCS, Wipro and Infosys and their rising contribution in terms of services exports.

The public sector drive to spread the benefits of this burgeoning digital revolution to the Indian population through better digital infrastructure, increased connectivity, and digital empowerment is exemplified by the Digital India project. The Digital India project was launched in 2015, with three pillars related to digital infrastructure, digital services, and digital empowerment. The Aadhar project, e-panchayats and the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana were the key building blocks of this approach. One public sector flagship project which was specifically designed to bridge the digital divide across rural and urban India was BharatNet. Launched in 2011, the BharatNet Project is tasked with creating the National Optical Fibre Network India. A total of 2,50,000 gram panchayats spread over 6,600 blocks and 641 districts are to be covered by laying incremental fibre. BharatNet focusses on bringing high-speed broadband connectivity to rural India to enable access to various services such as tele-medicine, tele-education, e-health and e-entertainment.

However, notwithstanding the private sector’s global digital prowess and substantial public sector efforts, India’s digital divide has become acute across rural-urban spatial divides, population categories and states. The internet density in rural areas, where more than 60% of India’s population live, is still at 25%, compared to the internet density in urban areas, which is 90%. States like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh have very low internet use density. India’s digital divide problem is not just limited to the spatial divide. It is also one where various identities such as gender, class, caste, and geographic location play a crucial role. Separately, while revenue from e-commerce transactions has grown exponentially globally, it remains less than 5% in India. More than 80% of all retail transactions are still made in cash.

Covid-19 has exacerbated the country’s digital divide. Several essential services such as healthcare, education, banking, and financial services have quickly moved online. But in India, where more than half the population of 1.3 billion people is under 25 years old, as many as 80 percent of Indian students could not access online schooling during the lockdown. Digital solutions seem particularly useful in the last-mile vaccine delivery since they raise awareness of vaccine campaigns, enable access to vaccine campaigns, and register for vaccination all while ensuring limited human interaction. However, until the rollout of the new vaccine policy effective from June 21, pre-registration on the CoWIN portal was mandatory to book a vaccination slot. The lack of access, and affordability to devices coupled with digital illiteracy has made it difficult for various sections of the population to register for a vaccination slot online. Yet this sheer magnitude and significance of this digital divide, represents an enormous opportunity for India to power economic opportunities and bridge social divides in the nation.

Thus India, which is at the forefront of the private sector digital revolution, has a substantial public sector engine related to Digital India and is representative of an acute digital divide, is well placed to lead the design of a bridge of public policy interventions that can act as a helping hand across the digital divide. Yet beyond these threshold requirements, a public policy bridge also needs to promote three elements of PPP, namely investment in infrastructure, access, and a ‘people first’ design.

On 30 June, the government announced that the Bharat Net broadband project will be expanded to 16 states. The government has reportedly set aside Rs 19,041 crore in the form of viability gap funding. It is expected that over 3.6 lakh villages across 16 states of the country in a PPP mode. Given that execution of BharatNet projects are behind schedule, the most recent indications by the government signalling private contracting out of BharatNet projects is welcome.

Global experimentation suggests success in promoting digital access for remote communities through satellite broadband connectivity needs to become a priority. Projects such as the one between the Asian Development Bank and Kacific Broadband Satellites International Limited to provide affordable satellite-based, high-speed broadband internet connectivity to countries in Asia and the Pacific typify this. Separately, the Kenyan Education Ministry, the UK Department for International Development and Avanti Communications Group are providing satellite connectivity to 245 rural and remote schools for more than 1,80,000 children in Kenya. Yet in both cases a PPP was critical. A PPP pilot of this type in India could be basis for a scaling up of this model.

While traditional PPPs have helped bridge the infrastructure gap in a bid to advance economic development goals, there has been a disproportionate focus on economic value. It appears that the value for people, and communities, may not have been a primary metric in designing and implementing such models. Thus traditional PPP models did not fully embrace the needs of the users. Users simply could not afford the services offered by such models. These PPP models would then have to rely on government subsidies. Consideration should therefore be given to ‘people first’ PPPs. People-first PPP is an initiative led by the UNECE’s PPP Centre for Excellence in Geneva and supported by the International Sustainable Resilience Centre and the World Association of PPP Units and Professionals. The cornerstone of this model is to ensure that ‘people’, and the ‘value for the people’ are among the chief stakeholder priorities. The focus of such partnerships is, inter alia, on improving the quality of life of communities by promoting well-being, gender equality, and creating sustainable jobs. By making digital literacy and capacity development core to the PPP policy design for bridging the digital divide, a broad band of users can be given productive means of employment to sustain infrastructure PPPs and effectively enable access to digital infrastructure.

Lastly, at a time where there are battles between state regulators and technology companies, bridging the digital divide can provide a 21st century way forward. History may be useful in terms of where we come from but not necessarily in terms of where we are going. So, emotive references to past colonial exploitation of the 18th and 19th centuries, previous generations of antitrust battles of the early 20th century or pre-war protectionism may not be the best guide for new rules. Instead, a properly designed PPP policy may provide a 21st century engine to harness the power of market players for greater digital infrastructure, access, and literacy for the Indian population. In a vibrant Indian democracy, such a public policy-driven digital empowerment of the Indian electorate can help ensure responsible digital conduct in the interest of consumers and the larger public interest.

Arjun Goswami and Navya Alam are, respectively, Director, Public Policy and Associate, Public Policy at Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas. These are the authors’ personal views.