The cess we paid for years to improve schools has gone unused. Govt has no clue about its PSU investments. CAG reports are full of such tragi-comedies

When a citizen does not pay due taxes, the result is black money. Everybody gets worked up about it, and rightly so. But when the government collects taxes and does not use the revenue for the intended purposes – or even collects money for non-existent taxes, what would be the result? Grey money? That has been happening, and despite reminders from the supreme auditor, goes on happening surreptitiously.

This is the other side of public finance, which is revealed annually in the reports of the constitutionally authorised external auditor of the government, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG). Each of the 200-odd of them routinely exposes financial bungling, though only a few are called scams and go on to make headlines. The other reports are dutifully tabled in parliament or the state assembly: thus, reporting back to the legislature – to our representatives – if the taxes and expenditures they had approved have been properly accounted for. Little happens after that.

Take the case of cess, for example. Most of us do not know when we started paying it. None of us knows what happens to it either. Is cess – an additional tax levied to raise funds for a specific purpose – collected in very small amounts on various transactions or on income tax finally used for its intended purpose? No, according to a new report from the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG).

The CAG’s ‘Report No.2 of 2019 - Accounts of the Union Government - Financial Audit’, tabled in parliament on February 12, notes several instances of “deficiencies in Cess collection and utilisation”. The government has, for example, amassed Rs 94,036 crore – not a small amount – under ‘secondary and higher education cess’ (SHEC), since 2006-07 when it was first levied. All this money was to go to a dedicated fund, called ‘Madhyamik and Uchchtar Shiksha Kosh’. Till August 2017, the fund was not even created. Moreover, it “has not been operationalised so far”. Thus, the humungous amount has been retained in the Consolidated Fund of India (CFI), contrary to the purpose and procedure.

This is of course not a new problem. The report sadly notes, “This issue has been reported regularly in previous CAG Reports.”

Then there is the case of ‘under-utilisation of monies collected under the research & development (R&D) Cess’. “The R&D Cess Act, 1986 provides for levy and collection of a cess on all payments made for the import of technology. After creation of the Technology Development Board (TDB) in 1996, the money collected is to be disbursed as grants-in-aid to TDB. Rs 8,077 crore was collected under R&D Cess from 1996-97 to 2017-18. Of this, only Rs 779 crore (9.64 percent) was disbursed to TDB,” notes the CAG report.

Unused cess is one thing, and collecting a cess that has been withdrawn is straight out of a comedy film like ‘Golmaal’ or ‘Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro’. Read on: “Further, though the cess was abolished with effect from April 2017, Cess amounting to Rs 191.41 crore and Rs 1.14 crore was irregularly collected during 2017-18 and 2018-19 (September 2018) respectively.”

The government collected a total of Rs 2,14,050 crore under 42 types of cess in 2017-18. When goods and services tax (GST) was introduced from July 1, 2017, most types of cess were subsumed under it, major among which were krishi kalyan cess, swachh bharat cess, clean energy cess and cess on tea, sugar and jute. However, six categories of cess continue to be levied. These are: primary education cess, secondary education cess, education cess on imported goods, cess on crude petroleum oil, road cess, a national calamity and contingent duty (NCCD) on tobacco and tobacco products and crude petroleum oil.

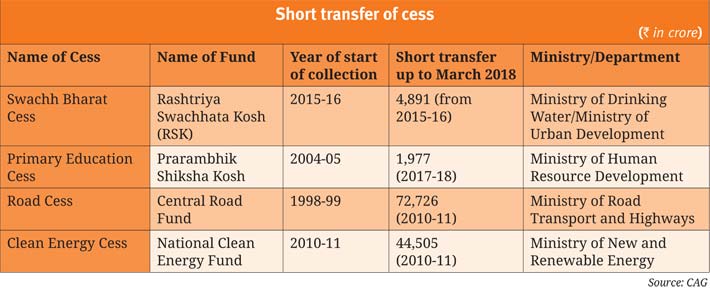

The CAG audit also noted “short transfer of cess collected in CFI to the dedicated non-lapsable fund in Public Account” as shown in the table. “Comments on short transfer of funds with respect to Road Cess and Clean Energy Cess have been repeatedly pointed out since 2010-11. “However, the accounting authorities have taken no action in this regard,” the report said.

Shortcomings

In money matters, the government obeys ‘general financial rules’ (GFR) which stipulate that the secretary to the government is the chief accounting authority (CAA) of the concerned ministry/ department, assisted by the financial advisors (FA) and chief controller of accounts (CCA) of the ministry/department. The CAG report highlights several “instances where the above authorities failed to fulfil their responsibilities resulting in shortcomings in transparency, presentation, disclosures, accuracy, classification, completeness and other discrepancies in the Finance Accounts of the Government of India”. Among them:

Opaqueness in accounts

Suppose a ministry or a department receives or spends money for a purpose that does not find a mention among the existing heads of accounting, then the transaction is put under something called ‘Minor head 800’. This category relates to ‘other receipts/ other expenditure’ of a ministry or a department, and it is to be operated only in cases when the appropriate Minor head has not been provided. Now, if such repetitive receipt or expenditure occurs, then it is the responsibility of the accounting authorities to create new and appropriate Minor heads. Indiscriminate booking of receipts and expenditure under Minor head 800 results in opaqueness in accounts: We can’t know where the money is coming from or going to.

The CAG notes that due to the failure of the authorities, Rs 20,855 crore was booked as expenditure under ‘Minor head 800-Other Expenditure’ during 2017-18. Six ministries/departments booked Rs 6,475 crore, representing more than half of their expenditure against 10 specific Major heads, under ‘Minor head 800’. In other words, we can’t know from account books how they spent Rs 6,475 crore.

On the other hand, 14 ministries/departments booked receipts of Rs 5,326 crore under ‘Minor head 800-Other Receipts’ (26 Major heads) which is more than 50 percent of receipts of Rs 6,228 crore.

The accounting authorities of these ministries/departments failed to take corrective action despite the fact that similar comments had been made in previous CAG reports in respect of these ministries/departments.

Short receipt of guarantee fees

Under Article 292 of the constitution, the government may give guarantees within such limits, if any, as may be fixed by parliament by law. The GFRs stipulate that the rates of guarantee fee would be as notified by the budget division of the department of economic affairs under the ministry of finance. Audit observed that the accounting authorities of five ministries/departments failed to realise Rs 1,144 crore towards guarantee fees during 2017-18.

The puzzle of PSU investments

The government is the biggest investor in the country: it has made a total investment of Rs 7,96,396 crore at the end of 2017-18 – a manifold increase over Rs 1,27,652 crore of 2016-17. If you suddenly invest six times more, it is understandable that you may not be able to know how much money you invested in which statutory corporations, government companies, other joint stock companies, cooperative banks, societies and so on. So, it should not be surprising that the equity investment amount on government books and the same on a PSU’s account book may not be, well, the same.

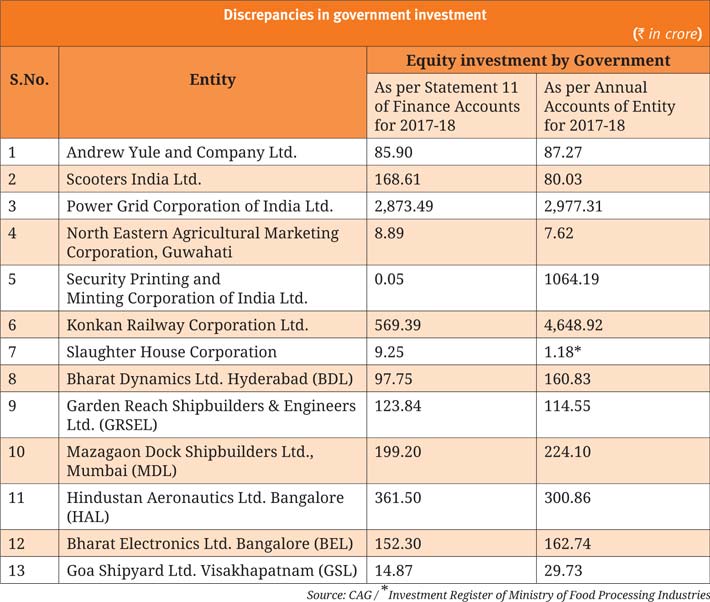

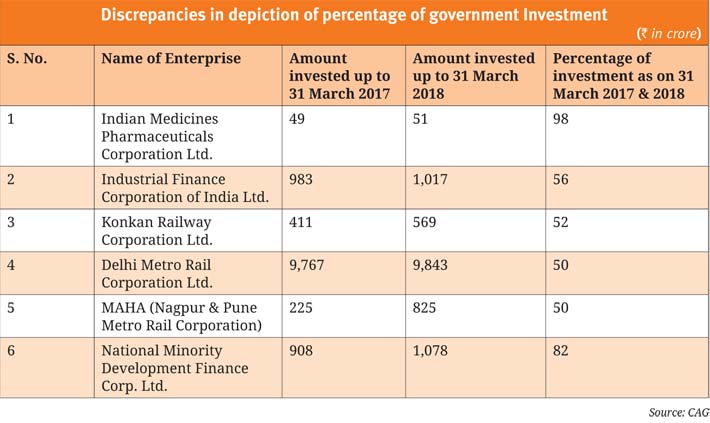

Statement 11 of the Finance Accounts of the GoI provides details of GoI investment in public sector and other entities. The accounting authorities of the concerned ministries/departments are responsible for the accuracy and completeness of details contained in Statement 11. The CAG audit found wide discrepancies in two books.

Thus, the government believes it has invested only Rs 0.05 crore in Security Printing and Minting Corporation of India. The firm’s annual accounts, however, claim that the government has an investment of Rs 1,064 crore – a difference of more than Rs 1,000 crore. There are a dozen other PSU entities where the two figures don’t match (See table on the previous page for the full list).

Moreover, for 17 entities, the GoI’s Statement 11 shows incomplete information about investment, face value, number of shares, total paid-up capital and percentage of government investment. When the main figures don’t tally, no wonder dividend figures in many cases don’t match either.

These are not instances specific to one regime: Many of these funny practices are chronic and stem from the irresponsibility or inefficiency of officials. These are also not cases of wilful cheating or outright corruption: Nobody benefits by collecting a cess that has been abolished, or by not updating government investment figures. But something is definitely wrong when as much as Rs 94,036 crore, collected from us to improve schools and make the next generation better educated, remains unused.

Action on the CAG findings should come from the public accounts committee (PAC) of the parliament or the assembly, after the report is tabled. However, as a Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA) paper of 2014 points out, “legislature does not make much use of CAG reports; it only uses it when scandals come up.”

ashishm@governancenow.com

(This article appears in the April 15, 2019 edition)