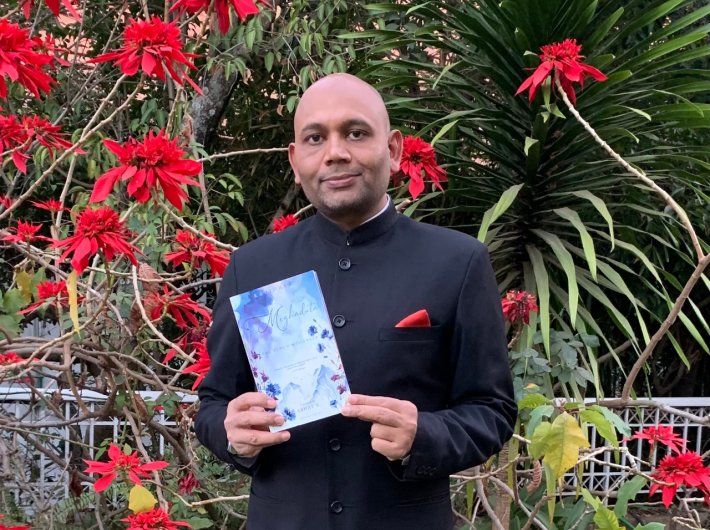

Interview with poet-diplomat Abhay K on his new translations of ‘Meghaduta’ and ‘Ritusamhara’

Being a diplomat is a fulltime job, in which Abhay K., an Indian Foreign Service (IFS) officer, spends most of his working hours. Like all diplomats and indeed the rest of us, he manages to make time for something that he finds as important as the day job. In his case, it is poetry – “the intrinsic need of our species,” in his words.

But there is no discord between the two roles. The diplomat (tactfully) and the poet (sensitively) co-exist peacefully. As his diplomatic career takes him from one continent to another, the poet finds new sensitivities in different places. His first collection of poems, ‘Enigmatic Love’ (2009), was subtitled ‘Love Poems from Moscow’, where he had been posted. Kathmandu and Brasilia were to follow soon. Cities changed, but what was common to them all was that they were all capitals. That inspired him to put together an anthology of poems about capitals.

Among his anthologies, there was ‘100 Great Indian Poems’ (2017), the sequel ‘100 More Great Indian Poems’ (2019) and ‘The Bloomsbury Book of Great Indian Love Poems’ (2020). Was it the lockdown-induced productivity or other inspirations, Abhay has been even more prolific in the last couple of years. In 2021, he came up with his translations of two great Sanskrit poems by the mahakavi Kalidasa: ‘Meghadutam’ and ‘Ritusamhara’.

For ‘Meghaduta: The Cloud Messenger’, the great Sanskrit translator A.N.D. Haksar said, “Abhay K.’s translation … gives a fresh sense of the original”. Pritish Nandy, an accomplished poet who too has rendered Sanskrit poems into English, said of ‘The Six Seasons: Ritusamhara’: “Unquestionably the most wonderful translation … This is the Kalidasa you want to read.”

On this Sanskrit turn, Abhay K. answered a few questions, as other matters also cropped up.

If we can begin with the obvious question, what immediately inspired you to these two classic poems? You would’ve read them earlier, but what prompted you to consider translating them into English – when several versions are already available?

Abhay K.: In March 2020 when I read a poem titled ‘Lockdown’ by UK poet laureate Simon Armitage, published in the Guardian, UK. He had penned the poem in response to the lockdown imposed in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. The poem made a reference to Kalidasa’s poem ‘Meghaduta’ or ‘The Cloud Messenger’. While I was posted in Nepal (2012–2016), I often heard people mentioning that the mythical city of Alkapuri in Kalidasa’s ‘Meghaduta’ is believed to be the present day Kathmandu. However, I had never had the opportunity to read the whole poem either in its original Sanskrit text or its English translation.

I started reading ‘Meghaduta’ in March 2020 and was completely immersed in it for days and weeks. I first read its English translation by H.H. Wilson (1814) and then by Col. H.A. Ouvry (1868), afterwards a translation of ‘Meghaduta’ by Mallinatha (1895) with exhaustive notes and finally a translation by Chandra Rajan published by the Sahitya Akademi (1997). More translations I read, the more I felt the urge to translate it myself into contemporary English. I had studied Sanskrit earlier and it came handy while translating ‘Meghaduta’.

Translating ‘Meghaduta’ was a transformative experience. During the process of translation, I wrote an article titled ‘What Kalidasa Teaches Us About the Lockdown, Loss of Biodiversity and Climate Change’, which was published in the Madras Courier in April 2020. The article was widely read and commented upon. It brought me laurels from A.N.D. Haksar, translator of many Sanskrit texts, many published as Penguin classics. He wrote—“Abhay K.'s translation of Meghaduta gives a fresh sense of the original.” It boosted my confidence and I was motivated to find a publisher for my translation of Meghaduta. The book was published by Bloomsbury India in June 2021. It encouraged me to translate Kalidasa’s another classic poem ‘Ritusamhara’, which is about the changing seasons and their impact on the rhythm of nature and people’s lives in ancient India.

You speak Magahi, Hindi, English, Russian, Nepali, and Portuguese and you know French and Sanskrit. That in itself should count as an achievement, but as for Sanskrit, did you have to brush up your knowledge for the task of translation?

Abhay K.: That’s right. It took me a while to brush up my Sanskrit. Paying attention to the roots of each of the Sanskrit words helped me a great deal. I also benefited from translating ‘Meghaduta’ and ‘Ritusamhara’ and my Sanskrit vocabulary is much richer now.

These two poems, unlike Kalidasa’s epic poems and plays, are devoted to Nature, and you rightly place it in the context of the new movement of Ecopoetry. Kalidasa is, you note, the original ecopoet. He goes against the strand of Indian tradition of worshipping ‘Mother Nature’, and finds sensuous delights in the environment. You have been especially sensitive towards this new relevance of his poems in the age of climate change, highlighting the flora and fauna in them. Can you share with us any response on this aspect?

Abhay K.: Both ‘Meghaduta’ and ‘Ritusamhara’ would be unimaginable without all the plants and fragrant flowers described in detail by Kalidasa. This is why the both these poems should be of interest to the current generation as we deal with biodiversity loss and climate change today. Can we treat of nature as a sensual being presented by Kalidasa in ‘Meghaduta’ and ‘Ritusamhara’ to transform how we see nature — from mother to beloved, from revering it to loving it and from being separate from it to being part of it? Can it help us in protecting nature if we start to see clouds, rivers, plants, trees and animals as sensual beings? I think a change in the way we look at nature can transform our relationship with it.

For example, ‘Meghaduta’ also highlights the importance of flowers, plants, animals, seasons, rains, rainbows, winds, sun, moon, stars, stones, rivers, mountains among others things—animate and inanimate, in our love-life, without which we would gradually become bio-robots obsessed with numbers and statistics, dealing with various kinds of growth rates, and living a dismal life on a planet marred by loss of biodiversity and extreme climatic events. Here is a stanza from Meghaduta:

Where at dawn, the night-path of the amorous women

are revealed by fallen Mandara flowers from their ringlets,

golden lotuses torn, fallen from their ears,

threads of their necklaces broken, pearls scattered,

fragrant from the perfume of their breasts. [67]

The treasure of Sanskrit poems – indeed literature – is immense. Like every generation, the current one is rediscovering it and your translations help the new readers. So, what do you plan to take up next in this series?

Abhay K.: I’m not translating anything else from Sanskrit at this moment. However, translating these two classic poems of Kalidasa inspired me to write this book-length poem which commences its journey in Madagascar and follows the path of the monsoon invoking the rich flora and fauna, languages, cuisine, music, monuments, landscapes, traditions, myths and legends of the places through which monsoon travels. Monsoon seemed to me as a perfect messenger to carry my message from Madagascar to my beloved in the Himalayas with its origin near Madagascar in April and its journey across the Indian Ocean and the Indian subcontinent to reach the high Himalayas in June every year before retreating to Madagascar after September.

‘Monsoon’ weaves the beauty and splendour of the Indian Ocean islands of Madagascar, Réunion, Mauritius, Seychelles, Mayotte, Comoros, Zanzibar, Socotra, Maldives, Sri Lanka, Andaman & Nicobar and the Indian subcontinent into one poetic thread.

As ‘Monsoon’ is inspired from Kalidasa’s ‘Meghaduta’, the comparisons between the two are natural. ‘Monsoon’ has the same backdrop of two separated lovers longing for each other as in ‘Meghaduta’. While ‘Meghaduta’ covers the journey of clouds from Ramagiri hills in central India to the mythical city of Alkapuri near Mount Kailash, ‘Monsoon’ covers a much wider canvas stretching from Madagascar to the Himalayas. ‘Meghaduta’ has 111 stanzas of four lines each written in Mandākrāntā meter, whereas ‘Monsoon’ is a quatrain or ruba’i of 150 stanzas written in free verse. While ‘Meghaduta’ gives descriptions of mythical creatures such as sylphs, eight-legged animals and plants such as Kalpataru along with the diverse flora and fauna of Kalidasa’s time, ‘Monsoon’ not only depicts the rich flora and fauna of the places through which it travels but also highlights their vivid colours and sounds, tastes and aroma of the rich cuisine, history and legends, landscapes, monuments, among others.

In this poem I have also tried to weave together monsoon inspired architecture, such as the Monsoon Palace in Udaipur, Badal Mahal or Cloud Palace in Kumbhalgarh, Anup Talao at Fatehpur Sikri where Tansen used to sing his Megh Malhar, Deeg Palace near Bharatpur with its nine hundred fountains trying to recreate monsoon rains, and the monsoon festivals of Haryali Amavasya and Teej and the forgotten 17th century monsoon raga Gaund, which was once popular in the court of Mughal emperor Shah Alam. ‘Monsoon’ is a homage to the rich natural world of the Indian Ocean islands and the Indian subcontinent, their vibrant cultures and traditions and to the great Kalidasa who gave us ‘Meghaduta’ and ‘Ritusamhara’.

Hope the readers will enjoy the sumptuous journey ‘Monsoon’ takes them on all the way from Madagascar to Srinagar and back.

There must have been other diplomats who wrote poetry – or poets who did diplomacy, but the prototype seems to be Octavio Paz. His official residence during his India years, on the Prithviraj Road, must have been an inspiring landmark for you in your younger days. We’d like to hear from you about any cross-pollination between these two vocations have you chosen.

Abhay K.: Poetry and diplomacy have a lot more in common than it appears to our eyes. Poets and diplomats both deal with words and employ figures of speech to communicate their thoughts and feelings. Both choose their words very carefully. Emily Dickinson’s ‘Tell it but tell it slant’ is valued by poets as well as diplomats. Brevity of expression, or to say more with fewer words, is practised by both poets and diplomats. One needs to be sensitive to be a good poet as well as a good diplomat.

In fact, a number of poet-diplomats have excelled both in poetry and diplomacy, such as Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz, and George Seferis, who served as ambassadors of their respective countries and received the Nobel Prize in Literature. Octavio Paz as you have rightly pointed out was Mexico’s Ambassador to India and he has indeed been a great inspiration for me. In fact my poetry collection, ‘The Alphabets of Latin America’ (Bloomsbury India, 2020), is dedicated to the poet-diplomats of Latin America, including Octavio Paz and Pablo Neruda.

Saint-John Perse was the Secretary General of the French Foreign Ministry with the rank of an Ambassador, and had also won the Nobel Prize in Literature. There are several other poet-diplomats across the world who excel both in the art of poetry and diplomacy. Therefore, I believe there is a connection that needs further exploration.

I think poetry connects us at a deeper level, no matter where we come from. Reading and sharing a poem creates lasting bonds, even among strangers. Its universal appeal reaffirms our common humanity and transforms our minds. Poetry, like other art forms such as music, dance, painting… helps us in promoting dialogues across cultures.

I would like to quote the words of French writer Françoise Sagan—‘I shall live badly if I don’t write, and I shall write badly if I don’t live,’ to present my case. I’ll be a mediocre diplomat if I don’t write poetry and a mediocre poet if I am not a diplomat. For example, in December 2021, I was invited to guest edit the ‘Madagascar Literature Month’ by the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative and while interacting with Malagasy writers I learnt about ‘Ibonia—the Malagasy Ramayana’, as well as a book published in 1951 that lists over 300 words from Sanskrit in Malagasy language. I also learned that Madagascar’s greatest poet Jean Joseph Rabearivelo was inspired by Rabindranath Tagore’s poetry and mentioned him in his poem number 15 in his poetry collection ‘Translated from the Night’. These facts are of great value for cultural diplomacy. I would not have come to know about these if I was not interested in poetry.

When I was posted in Kathmandu, I started a monthly poetry event named ‘Poemandu’ which ran for 39 months. In Brasilia, I continued this monthly poetry reading with a different name ‘Cha Com Letras’ for 36 months and the trend continues in Madagascar with the name ‘LaLitTana’. So far 14 editions of ‘LaLitTana’ have been organised. These poetry events brought together a number of poets and gave them recognition, inspiration and support to continue writing poetry.

Apart from poems – written, edited, anthologised or translated – put together in the form of printed books, you have been a lyricist, an artist and much more that we know little about. Please tell us more about your avenues of creative expressions, of explorations of the world.

Abhay K.: My first book River Valley to Silicon Valley (Bookwell India, 2007) was in fact a memoir for the first 25 years of my life. It also contained my first poem ‘Soul Song’:

I was always here

As blowing wind or falling leaves

As shining sun or flowing streams

As chirping birds or blooming buds

As the blue sky or empty space

I was never born, I didn’t die.

I have been painting since 2005. I started painting almost at the same time I started writing poetry in Moscow. My artworks have been exhibited in Paris, St. Petersburg, New Delhi and Brasilia. Being a diplomat I travel a lot and that makes me aware of global issues that get channeled into my art works. My solo exhibition in New Delhi in 2012 titled ‘We have come far’ addressed issues related to environment and spirituality.

My last solo exhibition at the National Library of Brasilia, titled ‘One Planet,’ aimed to raise awareness about the triple threat of climate change, biodiversity loss and environmental pollution that our planet faces.

I wrote ‘Earth Anthem’ in 2008 in St. Petersburg, Russia one night, inspired by the Blue Marble image of our planet taken from space by the crew of Apollo 17 and by the ideals of ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’ (the whole Earth is a family) from Maha Upanishad. The idea behind writing ‘Earth Anthem’ was to celebrate the beauty and diversity of our planet from a cosmic perspective (‘Our cosmic oasis, cosmic blue pearl/the most beautiful planet in the universe’), express the unity of life on Earth (‘united we stand as flora and fauna, united we stand as species of one Earth’), to emphasise unity in diversity (‘diverse cultures, beliefs and ways/we are humans, Earth is our home’), to show solidarity with one another (‘all the people and all the nations/one for all and all for one’) and finally uniting to give our highest reverence to our planet (‘united we unfurl the blue marble flag’).

It means a lot to me as it sums up my world view, my philosophy of being on Earth. ‘Earth Anthem’ has come a long way since I wrote it in 2008. It has been translated into more than 150 global languages, played at the United Nations in 2020 to mark the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, featured in over 200 publications across the globe including the BBC and The Christian Science Monitor. UNESCO described it as “an idea that can help to bring the world together,” and it was performed by the National Symphonic Orchestra of Brazil and the musicians of the Amsterdam Conservatorium, was set to music by violin maestro Dr. L. Subramaniam and was sung by Kavita Krishnamurti. Over 100 poets, artists, singers, musicians, professors and people from different walks of life from across the world came together to read Earth Anthem to mark the 51st Earth Day on 22nd April 2021. It became one of the key global events on this occasion. I would like that someday our planet has a common Earth Anthem, which every person Earth can sing.

I also wrote a South Asia/SAARC song which was extensively played during the last SAARC Summit in Kathmandu in 2014.

I penned a Moon Anthem, which has been put to music by Dr. L. Subramaniam and sung by Kavita Krishnamurti. It was played live on major Indian TV channels hours before the landing of Chandrayaan on the moon in September 2019. I have also penned anthems on all the planets in our solar system, which have been received well.

Rilke has described poetic duty as “Ein zum Rühmen Bestellter” — “the one whose task it is to praise.” I want to celebrate the beauty and diversity of our planet in my poems, sing the places I visit, capture my feelings of wonder, record my experiences of meeting people living in different parts of the world, and create a poetic portrait of our planet. I would also like that someday an institution of Earth Poet Laureate is created to celebrate the beauty and splendor of the biodiversity of our planet and promote ecopoetry globally.

I love travelling and taking photographs. Someday I would like to an exhibition of my photographs taken across the world.