A biography of Gujarat’s first novelist offers the glimpse of the dawn of modern India

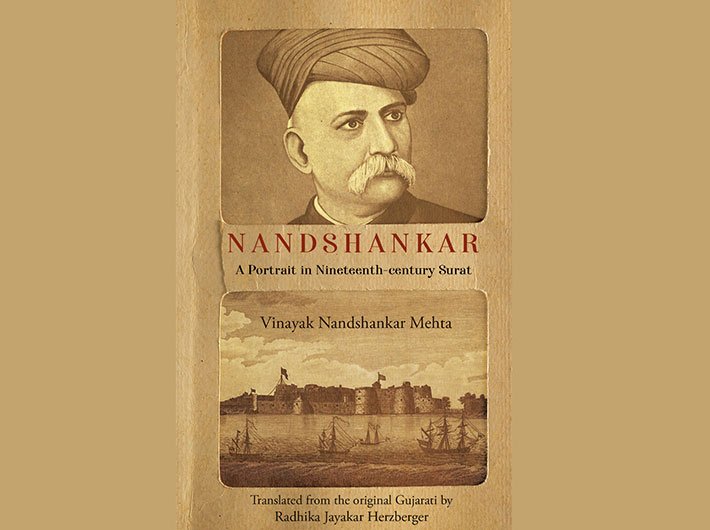

Nandshankar: A Portrait in Nineteenth-century Surat

By Vinayak Nandshankar Mehta

Translated from the original Gujarati by Radhika Jayakar Herzberger

Orient BlackSwan, xxx+257 pages, Rs 775

Nandshankar Tuljashankar Mehta (1835–1905), an eminent educationist and administrator, is acknowledged as Gujarat’s first novelist. His ‘Karan Ghelo’ (1866) was depicted the life of Gujarat’s last Rajput king, Karan Vaghela (1296-1305), and inaugurated the modern literary genre of fiction in Gujarati. Published in the immediate aftermath of the 1857 rebellion, harking back on the medieval times, it was a tale reimagining the glory of Gujarat before the fall. In the newly emerging print culture, readers were entranced by the experience of reading a long story, even if its narrative was weak. It underwent many reprints, and in 2015 it finally came out in English too, in the translation of Tulsi Vatsal and Aban Mukherji (Penguin).

In 1916, the author’s son, Vinayak Mehta, published a biography, ‘Nandshankar Jeevan Chitra’, making it the first of its kind, a filial tribute in this form. Today, it also presents a picture of Surat, the novelist’s home and a preeminent centre of commerce and culture on the west coast at that time. It was a unique time: with colonialism, modernity making its home in India. The English-educated class – Mehta was one of them, and so was M.K. Gandhi – was trying to find a middle ground between the world that was disappearing and the new world that was taking shape. With a foot in each of the two realms, their struggle was to retain what was good in the tradition as the tomorrow was making its entry with the speed of telegrams and railways.

In the turbulent time of 1860–1880, Surat was witnessing a high tide of creativity as the young Nandshankar, along with luminaries like Narmadashankar, Navalram and Mahipatram, dominated the Gujarat literary scene.

Vinayak Mehta was himself in the same class, educated at Elphinstone College in Bombay, Kings College of Cambridge University, and briefly at Heidelberg University in Germany. He narrates Nandshankar’s eclectic life against the backdrop of this vibrant cosmopolitan port and its changing political fortunes between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In the biography, he creates a composite picture of the rich cultural life of the period from fragments: remembered conversations, songs, poetry, witty anecdotes, and sketches of eccentric teachers, inept physicians and alcoholic judges.

The biographer-son presents facets of his father’s life: his boyhood shaped by British schoolmasters, Nandshankar as administrator, and Nandshankar as author of the historical novel. Drawn against a vivid and colourful backdrop of a changing culture, Nandshankar is presented as a man who navigated the disruptive aspects of modernity with grace and integrity. The biography, the outcome of historiography and historical craft combined with Vinayak Mehta’s literary and aesthetic sensibilities, reveals a work of astonishing eloquence, erudition and foresight.

Radhika Jayakar Herzberger, the renowned Indologist and educationist, fulfils the same filial duty in undertaking this translation – she is the granddaughter of Vinayak Mehta. In this nuanced and meticulously researched translation, she traces a hundred years of Surat’s social history, while carefully unravelling concerns important to the biographer and his times, and gently reading between the lines to uncover the hitherto unknown and untold story of his father’s life. Her scholarly introduction not only puts the biography in perspective but also gently ushers the reader into the forgotten era.