Excerpt: In ‘Invaluable’, Somik Raha recalls Swami Ranganathananda’s lecture, and offers tips on aligning our decisions with our values

Invaluable

By Somik Raha

IndiePress, 316 pages, Rs 701

From coding at age 12 to a deep dive into philosophy, Somik Raha, raised in India, combines his Eastern upbringing with over two decades in the West. With a deep passion for both Western and Eastern philosophies, Raha offers readers a uniquely enriching perspective in his book, "Invaluable: Achieving Clarity on Value," exploring the human aspect of technology.

From coding at age 12 to a deep dive into philosophy, Somik Raha, raised in India, combines his Eastern upbringing with over two decades in the West. With a deep passion for both Western and Eastern philosophies, Raha offers readers a uniquely enriching perspective in his book, "Invaluable: Achieving Clarity on Value," exploring the human aspect of technology.

In a world where decision-making often feels overwhelming, "Invaluable" serves as a much-needed guide to aligning choices with personal values.

A groundbreaking book that helps readers clarify their values and integrate them into daily decisions, inspiring a fulfilling life. Each chapter empowers readers on a journey of self-discovery, guiding them to understand their unique values blueprint.

In today's complex world, it can be difficult to make decisions that align with our values. Invaluable fills an important gap in decision-making: achieving clarity on our values and integrating them into our decisions consciously. People already have unique values waiting to be unpacked and articulated across diverse work contexts. Invaluable offers a holistic framework to aid its discovery, testing and succinct communication.

This homage to values is brought out through stories, philosophy, poetry, citizen science and embedded podcasts. By the end of this book, the reader will have a deeper understanding of their singular values blueprint, making intentional decision-making an enriching process. You will also be inspired to live a life that is true to your values.

Raha holds a PhD from Stanford, and his focus lies in achieving clarity on value. Currently based in the Bay Area, he continues to explore the intriguing intersection of technology, philosophy, and humanity.

Here is an excerpt from the book:

THE PURPOSE OF BUSINESS

BUSINESS IS SERVICE

A favorite uncle of mine posed me a riddle. “There was a grocery shop near the train station and another one near a bus station. There was a third one that was in the middle. Can you guess which one did the best business?” Take a moment to think about your answer to this question before reading further. My thoughts at the time were around trying to figure out whether a train station would get more grocery customers than a bus station. In order to answer which grocer did the best business, I first had to get clear on the purpose of business. I was reminded of my fifteen-year-old self in a college auditorium in Chennai.

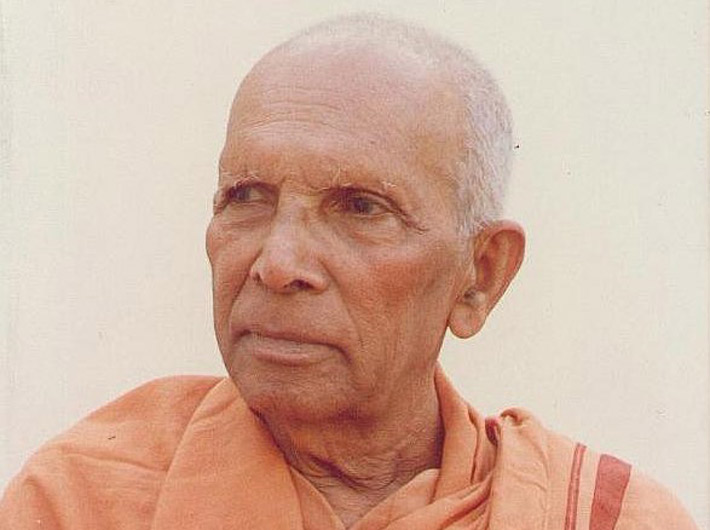

I was a high school senior at the time, and my father had sold me into attending a monk’s talk by saying, “There is this octogenarian monk I know who is going to give a talk on business. He never repeats himself. You also won’t forget what he says.” The lecture was organized by a company in India, and the speaker was Swami Ranganathananda, the head of the Ramakrishna order of monks at the time. It was only decades later that I was struck by the oddity of a monk being asked to give a talk on business to those who were in business, but such contradictions are a part of daily life in India.

The Swami started very simply, as my father had predicted, never repeating himself. He got right to it and defined business. “Business is service. You serve others, and in return for that service, people compensate you out of gratitude. Don’t worry about compensation; focus instead on being of service. For if people are truly served, your compensation is bound to come.”

I remember nodding. Yes, it made total sense. Why would anyone think any other way about this? And yet, days later, when I was faced with my uncle’s riddle about success in business, my very active and intelligent mind took me away from the clarity that Swami R had provided. As I grappled with the question using simple reasoning, I could not answer. My uncle grinned and eventually answered, “It was actually the grocer in the middle. For his behavior with his customers was the best, and they all loved him.”

The light bulbs went on for me. By focusing on the volume of customers in seeking an answer to the riddle, I had latched onto an industrial revolution mindset of viewing the customer as a widget feeding into profit. I had not left room for service as a foundational motive. Our service orientation is the basis for how we behave with others, and the connections we form with them. That grocer in the middle was focused on serving his customers well, and his service orientation came through in his behavior toward his customers. As Swami R had laid out, his compensation was bound to come.

If service is a primary motive of business, then in order to know whether my customers are being served, I should care a lot about their satisfaction. Not only their satisfaction, but also their delight.

As a fifteen-year old, I didn’t know much about customer satisfaction metrics. Nor did I know about ethnographic analysis and human factors research that could give us deep access into the holistic experience of a customer, far beyond what a few quantitative measures can do. It is not that hard to imagine that if you have happy customers, they will keep you in business. Many great businesses understand this today and instruct us to remember that the “customer is king” or the “customer is always right.”

So, when it comes to business, is service a means or an end? If we were to think of it as a means, and the end is profit, then the business world and business schools have much to offer on the link between the two. But what if Swami R meant that service was the end, and profit and everything else in business was a means to being able to serve? How does that reorientation feel? Does the distinction between means and ends even matter?

Service is a heavy word. Not the least because its roots come from the Latin servitium, or the condition of being a slave. When we are lectured about service in the context of business, it is often a leader wagging a finger with a “thou shalt” attitude. This leader is accountable for creating a profitable business, shareholder value or impact, and sees being of service as a path to achieving those objectives.

There is already a big pile of things on my to-do list, and now here comes this unclear “being of service” commandment. A new term has entered the lexicon, “servant leader,” which refers to a person who thinks about others before thinking about the self. Another wonderful stick to get beaten by. Feeling heavy already? Does the image of a martyr with no will or creativity surface for you? Why does service feel so passive, where I have to go wherever the customer wants me to go? The customer could be external, or someone my team supports, or my own boss or colleagues. If my service is a means to the greater end of business profits or shareholder value-creation or even someone’s view of impact, then there comes a point when I can no longer find it authentic to serve. Then the dictum of “being of service” rings hollow and the carrot of enrichment, whether financial or impact-related, ceases to inspire me.

What if Swami R’s definition of business is pointing us in the exact opposite view of service, where it is an end and not a means? This is now getting into dangerous territory. Being a diligent reader, you remind me that the promise of this book is about finding our philosophical insights through the narrow construct of counting and not through discourses from monks. You point out that everyone around you is so stressed about creating profits, shareholder value or making an impact. What makes this monk’s suggestion to flip the paradigm valid?

Indeed, we will have to revisit the Swami’s exposition after we have taken a walk through a humble counting construct.

[The excerpt reproduced with the permission of the publishers.]