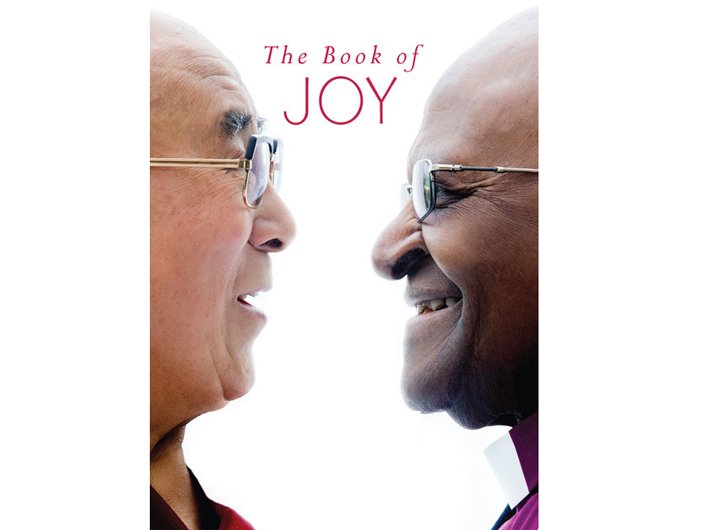

Book Review: ‘The Book of Joy’ says compassion for others is the source of our happiness

“Deep down we grow in kindness, when our kindness is tested.”

‘The Book of Joy’ (first published in 2016) introduces two prominent personalities, the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and discusses how because (and not despite) of all the hardships that they have suffered for over fifty years, they are the two most joyful people on the planet. The book attempts to answer the question we all have searched for in our lives: how to find joy in life’s inevitable suffering? The book gives a unique perspective to answering this question because not only do we learn from the wisdom of two wise and kind men, but also it relates their teachings to science.

The book defines “joy” as a state of mind and heart, which unlike happiness is not dependent on external circumstances. Before the book ventures into any insight, we come across this quote: “Suffering is inevitable, but how we respond to that suffering is our choice”, and this becomes the basis for further learning. One of the easiest ways to dissolve our anguish and pain is to shift our perspective and begin understanding others’ sufferings. From this comes the realisation that we are not alone, which alleviates our pain.

The idea is to develop empathy and compassion in ourselves. Life is going to come down on us, but the Archbishop reminds us to ask a deceptively easy question: How can I use this as something positive? The Dalai Lama narrowly escaped from his country and has been in exile for decades. But this suffering made him the person he is. He is now more compassionate towards other people’s pain. We journey through Nelson Mandela’s life in prison for 27 years, the Archbishop’s struggle during the Apartheid and learn the same lesson: nothing becomes beautiful without suffering. Compassion for others is the source of our happiness.

The book complements this learning with the research of psychologist Sonja Lyumbomirsky who also studied that our happiness is directly related to the ability of our mind to reframe any situation in a positive light, our ability to experience gratitude and our choice to become kind and generous; the exact teachings from the Dalai Lama and the Archbishop.

The book also condenses the findings of Richard Davidson, a neuroscientist, on happy brain. Our well-being is determined by first, our ability to remain in a positive state (by developing love and compassion); second, our ability to recover from negative states; third, our ability to focus and avoid mind-wandering; and last, our ability to be generous.

To these findings, the book takes us back to the mind of our two spiritual leaders, who explain to us that an individual, no matter how powerful, cannot survive without other human beings. Hence, the pursuit of our well-being truly lies in helping others and making more friends. When someone asked them, “how does one make friends?”, they explained, through trust. A genuine sense of concern for others’ well being will bring trust, friends and love. It is as simple as that.

Over the course of several more chapters, they also answer questions about how one should deal with fear, stress, grief, despair, loneliness, envy, and other negative feelings. At this point, the reader should be tempted to pick up the book and go through the details as it has the surreal power to instantly unburden a heavy heart. The crux of the learning remains: Our time on earth is destined to become more good, more loving, and more compassionate. This comes through learning. And learning happens when something happens that tests us. The book explains how suffering can either embitter us or ennoble us. The only difference lies in finding meaning or redemption for our suffering.

The following chapters of the book journey through the importance of developing mental immunity, the role of expectations, trouble with a self-centred attitude, among others. It also delves into the importance of meditation and how it gives us the freedom to reflect and choose one’s response, instead of merely reacting to perverse situations. The second half of the book gives us profound pearls of wisdom as it describes the eight pillars of joy: forgiveness, gratitude, compassion and generosity (qualities of heart); perspective, humility, humour and acceptance (qualities of mind).

This review tries to capture the essence of each chapter, but it is only the reader who can do justice to and imbibe the many spiritual teachings that this book offers. Among the qualities of heart, the chapter on forgiveness is easily one of the best. It begins by discussing how mothers who had seen their sons murdered during the Apartheid, when confronted with the murderers, simply forgave them. One of the mothers embraced the person responsible for killing her child and said “my child”. The chapter doesn’t just stop there; it is filled with instances of similar kinds of nobility and strength. Forgiveness is the only way to break the cycle of hurt or revenge. It is the only way to heal.

The next chapter on gratitude helps one move away from counting the burdens to counting the blessings of life. To illustrate its poignancy, the chapter discusses how Anthony Ray Hinton who was wrongfully accused, spent thirty years in a five-by-seven foot cell, in solitary confinement. The reader will appreciate the logic with which he forgave the people who had wronged him, and how it was connected to the gratitude he felt for the freedom he was granted. Compassion, as discussed before, gives us the courage to live with an open heart, which not only allows us to experience the pain of others but also their joy, enriching our lives. For instance, Hinton survived solitary confinement by focusing on the pain of his fellow inmates. His journey to bring about love and compassion in a loveless place is inspiring. Generosity, of money and time, is the natural extension of compassion. Helping others makes us feel valued and needed, bringing a sense of purpose to our lives, and bringing joy.

Among the qualities of the mind, a healthy perspective is for us to be able to see not just what we lost, but what we have gained (comes from stepping back and looking at any situation beyond our limited self-interest); humility reminds the readers that it is our vulnerabilities, frailties and limitations that we need one another; humour has the surreal power to diffuse the most tense situations – the ability to laugh at ourselves or the absurdity of the situation makes it easier for other people to communicate more honestly and compassionately with one another; accepting life’s inevitable hardships is the only way to come to the next critical question: how do we use this for something positive? The chapters do a wonderful job of reminding the readers that ultimately, love is the answer to everything.

The book take the reader through intimate conversations with the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Tutu and is filled with inspiring anecdotes, surprising humour in the grimmest situations, and many poignant moments of recalling love and loss. The book is an easy recommendation not just for learning the lessons to achieve a joyful life but also to experience the sheer vulnerability of the two most compassionate people in the world.

For instance, it stirs the reader when the Archbishop was asked if he forgave his father for treating his mother in a certain manner when inebriated or if he, himself asked for forgiveness from his wife for the pain that one of his decisions had caused her. The answers to both are delightfully peaceful. The author’s effortless portrayal of their joys and pain, and the ease with which one begins to relate to it, make it a must-read.