Understanding the causes and effects of seasonal migration vis-a-vis gender in Khohar village of Rajasthan’s Alwar district

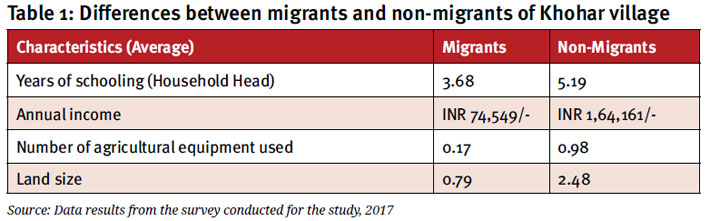

Khohar, a village located in Alwar district of Rajasthan, nestled in the foothills of Aravalis, is home to 154 families, most of whom are farmers by profession. The village has a large adult population with 65 percent over the age of 18. The village educational levels are relatively low, with household heads having only attended an average of 4.6 years of schooling (Figure 1). Out of the total population of Khohar, 33.11 percent are medium farmers (1-4 bighas of land), 16.2 percent of them are large farmers (more than four bighas of land), and 50.6 percent of them are small farmers (equal to or less than one bigha of land). The small farmers are mainly migrating farmers. The village faces a rampant problem with water scarcity for all households, rich and poor alike. Procuring water for domestic as well as agricultural purposes is a critical issue they face every day. Lack of a water body in or around the village makes farming a challenging task, leaving the people having to rely only on rain to cultivate crops. The villagers are mostly unconnected to government programmes and benefits, which magnifies their plight. A consequence of these problems is that at least 30 percent of households actively participate in seasonal migration (Table 1), traveling to the rural belts of Punjab and Gujarat for cotton, rice, and wheat cultivation for almost eight months in a year. Upon return, they are mostly idle since no work is available in the village. The aspect worth noticing is that the villagers migrate with their entire families, including their children, spouses, and even the elderly in some cases. The village appears deserted most parts of the year with every other house being empty and abandoned for four to five months at a stretch.

As per the socioeconomic profile of the villagers of Khohar, their dependency ratio indicates an age-population ratio of those typically not in the labour force and those typically in the labour force. It is used to measure the pressure on productive population. In Khohar, the dependency ratio is very less, which is a positive indicator. However, due to child labour, the income earners of the village became high that is a negative indication of the socio-economic status of a village. The illness yearly is found to be very high due to migratory diseases, inadequate access to quality drinking water, lack of access to proper health facilities, etc. The sources of income are two or more than two as there is diversification in the livelihood options. The agriculture diversification index is an average value as the diversification is more only for the large farmers who have multiple agricultural options. The average land size is less than two bigah as only large farmers have more significant land area. Only large farmers own agricultural equipment. The average family size ranges from five to six. The average education status of household head is usually up to primary level.

Labour migration is a common phenomenon seen in almost every part of India. Leaving one’s home and place of origin in search of better employment and higher wages is a significant component of the livelihood of many. Throughout history, migration was primarily seen as a male-dominated process where the men of the household ventured out to other cities and towns to work. However, this scenario is changing fast with females accounting for 70 percent of internal migrants in India (UNESCO, 2013). Data trends indicate that female labour migration is on the rise, with a 101 percent increase between 2001 and 2011. Female migration for business increased by 153 percent, four times more than the rate for men (GoI, 2017). In Khohar, female migration is typical, with women participating equally and migrating with men and children for agricultural work.

Women of Khohar lead very challenging lives as migration is a necessity for them and the only means possible for earning a living guaranteeing survival. They have been migrating since they were children and saw their parents do so as well. Their education was interrupted because of the frequent migration, and many dropped out of school at a young age and never went back. The cycle continues with their kids being unable to go to school for similar reasons. All family members who are healthy and can participate in the fields work together to earn maximum returns from their migration.

The decision to migrate is a routine practice as the adults have witnessed this since childhood and appear to be unaware of any other source of employment. Deciding when and where to migrate is always the decision of the husband or household head, who is male in 93 percent of the migrating households. Migrating patterns are routine, and no one is willing to break the tradition or explore novel occupation avenues. A group of women explained how everyone in their families is illiterate, so no one will give a job to them anyway. Women also blame their husbands for being too lazy to think about any alternatives to this situation, resulting in them traveling to the same places every year for agricultural work.

While working on the fields in places where they go to, the women’s day starts at four in the morning, cooking food for the whole family in addition to other domestic chores, and then they begin work in the field that continues until six in the evening. Many families have small children and infants they have to leave under a tree or in a protected area near the fields where they work. Livability standards worsen with no proper housing, as they have to live on the fields. They set up makeshift shelters under which the family sleeps on the floor, with no electricity or water. One of the migrating women, Silo Devi, described how snakes creep around near the place they inhabit especially during monsoon season. Protecting themselves and their children from them is another task they struggle with. Certain contractors provide ration for cooking, but the women need to fetch water for drinking and other purposes from the nearby canal or streams. Living in such situations, one’s health is affected. Women are usually found nutritionally deficient and anaemic. Malaria and fever are common diseases that migrating villagers contract from their places of work.

An anomaly: A special case of female migration

There are a few women who migrate every year, leaving their families behind. Suman, a nineteen-year-old girl, talked about how her mother is the only member of her house migrating along with the neighbours in a group. Her father grazes livestock in the village and stays back with the children. Her mother migrates by her own choice and without expressed pressure from her family to do so. She opts for it as it gives her a source of additional income to sustain herself and her household. Such cases are extremely rare, but they demonstrate how ingrained the concept of seasonal migration is in the villagers. They do not think twice before choosing this as a source of livelihood even though it means enduring poor-quality living standards. At the same time, it illustrates a loosening of gender barriers where the husband is staying back with the kids while his wife migrates to another place for work.

Surviving under such unbearable conditions makes the whole process of migration extremely hard for all members of the migrating household. More so, the situation comes down harder on females as they are expected to perform all household duties and look after the children as well as work in the fields for long hours even if they are unwell. A study by Sandhya Mahapatro (2013) highlights how increased female migration is a sign of empowerment for women and that higher migration leads to an improved role of women in their households and in decision-making processes. Khohar, however, presents a different side to this. Living in a patriarchal system, migration trends of Khohar women are not characterised by empowerment but by forced and taxing situations from which they can’t seem to find a way out.

Table 1 shows the difference between migrants and non-migrants of Khohar across a set of socio-economic characteristics. The average years of schooling is higher for the non-migrants, but is still below satisfactory. The average annual income of a non-migrating household is more than a migrating household by 8.5 percent. However, if we were to quantify the social costs that migrating households bear, the gap would be much wider. The non-migrants, on average, use more equipment and tools to cultivate their fields and have larger sizes of land as well. A non-migrant household obtains close to three times more credit than a migrating one, making it possible to invest more in their agricultural fields for better returns.

Gender disaggregated perspectives of youth on the challenges they face due to migration reveal stark differences between boys and girls. When asked about one major problem they find living in Khohar, the boys cite unemployment and how tough it is to find a job in and around the village even after completing their graduation or skill training programmes. Girls on the other hand cite the lack of a proper school in the village for them to complete their education, as the current government school is only till 8th standard, and the closest higher secondary school is about ten kilometers away. This is one of the major reasons that parents don’t let girls study further.

Attendance records of a government school in the village Rajkiya Uchh Madhyamik reveal that out of the total students studying till 8th standard, 69 percent migrated in 2016–17. While the percentage dropped to 39 percent in 2017–18, the absolute difference in students dropping out between the two years was only thirteen. Though the boys get a chance to complete their education, their prospects are not that encouraging either. Regarding skills and education, the state of Rajasthan does not present a positive picture. Only 1.7 percent of its youth aged 15–24 have obtained any formal training (Aajeevika Bureau, 2014). Male youths in Khohar are trying to break this cycle of distress migration by trying to go to other cities for work, learn driving, for instance, and pursue that as a profession. One of the boys, Chandan, does stitching at home that he learned from his father. He planned to go to Jaipur for work. Though alternative livelihood options are slowly opening up for boys, girls are still not able to move forward because their proper schooling continues to be a distant dream. Like the limited opportunities available to them, their dreams are also limited. They only aspire to fulfill very basic and fundamental needs such as education, getting married on their own terms or possibly going to college.

Summing up

Migration should always be a choice; however, when it happens out of necessity, which is the case for maximum rural migrants in India, it is responsible for some challenges and hardships that migrating families have to face that ultimately affect their livelihood and quality of life. Inhabitants of Khohar are going through this exact phenomenon, with very few of them finding a way out or working in non-agricultural sectors to make a living. Women of Khohar are strong and resilient to be able to survive these grinding conditions. But their road to empowerment is a long one. Access to proper education is a major hindrance in addition to the other challenges they face. There is a definite need for government policies and programmes to be designed for such seasonal migrants and, more importantly, made accessible to villages like Khohar. The villagers continue to thrive with no social security, low wages, unstable jobs, and no legal protection against any of the unfair practices or disputes occurring at their places of work (Aajeevika Bureau, 2014). There is no check on the number of villagers migrating yearly, where they migrate, or how much they earn. Seasonal migrants are almost invisible entities in society with very little to no attention being paid to them or the harsh conditions they grapple with.

The road to a stable and satisfying life for the people of Khohar is filled with many obstacles. Yet it can be achieved with well-structured policies and programmes. Water scarcity, a significant factor for many villagers who opt for migration, needs attention and requires a solution. Rampant digging of borewells has led to no permanent relief for the households and is further depleting groundwater levels. This can be checked with proper regulations. The state can intervene with techniques like rainwater harvesting to help the people of Khohar have a proper supply of water for their fields as well as their homes. Awareness and education regarding the right techniques and tools for agricultural production and informing them of ways to maintain soil quality and cultivate less water-intensive crops will lead to maximum yields and minimum losses thereby proving beneficial. That way small landholders could also invest their hard work in their fields instead of cultivating other farms in distant locations under non-liveable conditions. Apart from this, having a higher secondary school in or around the village to ensure that both boys and girls receive complete education would be a huge step toward breaking this vicious cycle of poverty and distress migration.

The authors are with SM Sehgal Foundation, Gurgaon.

(The article appears in November 15, 2018 edition)