Water disputes are certain to keep Telangana and Seemandhra regions at loggerheads for many, many years

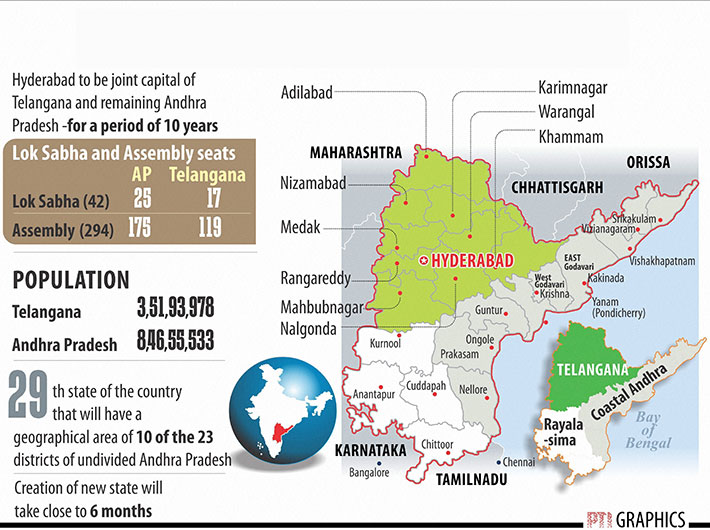

The Congress party has put the state of Andhra Pradesh to sword and divided it into two. On the momentous occasion of a Telangana state unfolding, here is a close look at an issue that is likely to remain thorny for both sides for some time: disputes over water.

The new state of Telangana, which got the UPA and the Congress party’s go-ahead on July 30, is the culmination of decades-long struggle and fulfillment of aspirations. But seeing this as a fairytale end to the vexed issue could be a big mistake. On the contrary, it would just be the beginning of yet another challenge; a mammoth task.

Despite calls for ‘parting of ways with grace and living harmoniously as friendly neighbours,’ water disputes are certain to keep the proposed Telangana and Seemandhra (or what remains of Andhra Pradesh – coastal AP and Rayalaseema regions) states at loggerheads.

ALSO READ: Telangana okayed, all eyes on AP assembly now

What were seen as partisan regional demands so far would now be escalated as full-blown inter-state disputes between Telangana and Seemandhra once they come into being. The trouble starts right at Jurala in Mahaboobnagar district, the entry point of river Krishna in present-day Andhra Pradesh. For long, it was felt that 811 TMC (thousand million cubic feet) awarded to the state by the Bachawat tribunal were insufficient. The state was used to utilise 748 TMC by 1975 itself.

What it got in addition later was a measly 60 TMC.

The hydroelectric project in Jurala, the first of its kind in the state, can store water throughout the year. The catchment areas of Krishna’s downstream projects –Srisailam and Nagarjuna Sagar reservoirs, besides Prakasam Barrage in Vijayawada – are eternally hard-pressed due to shortfall in inflows at Jurala.

The insufficient allocation and inflows in Krishna is already a matter of grave concern. The increase in the height of Almatti and Narayanapur dams in upstream Karnataka only adds a fresh nightmare to the predicament.

As a consequent impact, the state failed to get its due share of water through Jurala last year. Indeed, an irony, considering that the state sees around 3,000 TMC of floodwaters simply draining into the Bay of Bengal.

As a means to mitigate this problem, a diversion lift was proposed as part of the ‘Jalayagnam’ scheme. The work is yet to materialise. But when taken up in a newly created Telangana, it is only bound to make matters worse for the Andhra region.

Three subsidiary schemes of Jurala reservoir in Telangana – Kalvakurthi canal, Nettempadu lift irrigation project and the Bheema irrigation canal project – are at various stages of execution. Once these are commissioned, they are certain to leave the downstream catchment areas completely parched.

Issues over the Godavari

River Godavari poses an increased risk of its downstream catchments area going dry. With a total assured allocation of 1,482 TMC for the state, the river is the lifeline for Adilabad, Nizamabad, Karimnagar, Warangal and Khammam districts in Telangana and East and West Godavari districts in Andhra.

Sri Ram Sagar project (SRSP) is the first after the river’s entry into what is AP now. New projects in Maharashtra like the Babli dams, have caused water levels to dwindle here over the years. To harness rainwater in the backshores of SRSP, a lift irrigation system was initiated at Yellampalli.

Another project was initiated as part of Jalayagnam near Kaanthalapalli. The 20-TMC project was meant to increase storage capacity for Devadula pumping scheme. Two other projects – Rajiv Dummugudem and Indira Dummugudem – were planned in Khammam district.

Between this place and Sir Arthur Cotton Barrage near Dhawaleswaram lies the Polavaram major irrigation project. The controversial project, christened Indirasagar project, was the showpiece of Jalayagnam. It was planned to serve as a balancing reservoir to Dhawaleswaram barrage in East Godavari.

The two districts form a major part of the Godavari delta spread around the river before its confluence in the sea. As the bottom-end districts, they were awarded 260 TMC by the Bachawat tribunal.

The stiffest of opposition to the idea of splitting the state came from these two districts, long regarded as the rice bowl of Andhra Pradesh. Their fears centre around the fate and future of Polavaram irrigation project. The ambitious project, once completed, would entail an additional utilisation of 200 TMC by the two districts.

Dummugudem phase I and II and Kaantalapalli projects have remained nonstarters for a long time. Influential politicos of East and West Godavari are said to be the reason why they are in a limbo.

But the tables are certain to turn once the state of Telangana shakes them off their cobwebs and embarks on their construction. It will be nothing short of a death knell, capable of making the Polavaram project redundant.

The Bachawat allocation assures water for at least one crop a year for this region. But it has become a common trend to grow at least two, at times even three, crops in the highly fertile agricultural lands that includes the picturesque Konaseema, a delta in East Godavari district surrounded on all sides by water.

Last year, farmers of the two districts raised a banner of revolt against the state government for failing to assure water for the second crop. In a novel protest, they even announced ‘Crop Holiday’ to resent the government’s inaction.

What would be their response in a bifurcated scenario could be anybody’s guess. The irrigation and drinking water needs of the Godavari combine alone are likely to create one of the biggest water feuds between the two states.

But experts from the Telangana region are quick to take the wind out of their sails. They dismiss the argument that East and West Godavari districts would be deprived of their due share of water.

On the contrary, they claim, the two districts have been utilising close to 500 TMC. If their claims are right, the two districts are tapping an additional 240 TMC to their advantage. But being at the very end of the river, they were not robbing anyone of their share, it is contended.

The Rayalaseema crisis

Worst is the fate of Rayalaseema region. Most parts of the impoverished region are plain, barren lands, largely due to absence of a major water source. Their only lifeline is a small stretch of Tungabhadra river that eventually confluences in Krishna river in Kurnool district. The KC Canal project near Sunkeshula is supposed to irrigate lands in parts of Ananthapur, Kurnool and Kadapa districts. But water eternally eluded them due to diversions upstream.

Realising water scarcity in the region, the state’s previous chief minister, the late YS Rajasekhara Reddy, took upon himself a humungous task. The plan is to divert water from Godavari basin to Krishna basin and Krishna basin water to the Penna river basin. For this, a tailpond was planned between Dummugudem and Nagarjuna Sagar and another from Polavaram project till Prakasam barrage in Vijayawada.

The creation of Telangana jeopardises these Jalayagnam projects, which only means that the drought-prone Rayalaseema region will be deprived of around 250 TMC water.

But even in the midst of all this pessimism, some see positives in the state’s bifurcation. They hope that the fears of these disputes will lead to the institution of a regulatory body for water disputes. That way, the disputes that so far remained as local issues will be in for harmonious arbitration.

Also, Andhra Pradesh divided into two helps both states in optimum utilisation of Godavari river water. So far, Andhra Pradesh was able to utilise only 800 TMC, leaving another 600 TMC go waste into the sea.