As Europe grapples with the refugee crisis, it can learn a lesson or two from India in responding to it

At a time when Europe is inundated by the refugees escaping violence and wars in Syria, Libya and other Middle East countries, the world could, perhaps, learn a lesson or two from India’s experience of handling a 10 million refugee crisis on its land 44 years ago.

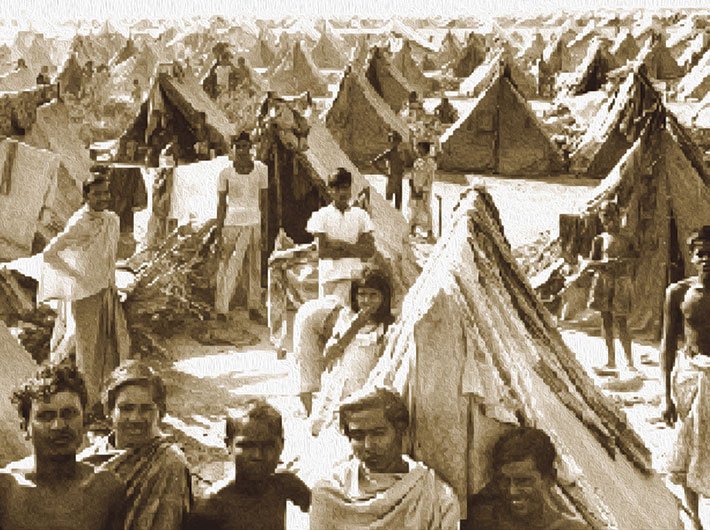

In 1971, the world was a bit different – engulfed in the cold war; no internet or mobiles to spread the gory truth about the Pakistan army’s brutalities on its own people in what was then the country’s eastern flank (now Bangladesh). Upset by the success of the Awami League party headed by the Bangla nationalist Sheikh Mujibur Rehman in general elections, the Pakistani regime had unleashed revenge in the East. The army launched a brutal crackdown in March 1971, ordering its men to kill and rape; lined up hundreds of Bengalis before the firing squads, massacred hundreds in universities and colleges, triggering a tsunami of people rushing to India. Nearly 10 million – initially Hindus and later Muslims too – had walked with bare souls and painful memories of atrocities to India over the next nine months. West Bengal, Meghalaya, Tripura and Assam were flooded with the refugees and a trickle had also reached the hinterlands of Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh by the end of the year.

To give it a context, India was a 24-year-old young republic and its economy was weak. (Its GDP was at $65.9 billion, or $116 billion at current rates, as against $2,066.90 billion in 2014.) It had to depend on the food aid from the US to feed its teeming millions. Therefore, hosting 10 million additional souls was no small task.

FL Pijnacker Hordijk, representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in India, was the first to raise an alarm over an impending humanitarian crisis in India on account of the military action in East Pakistan. On March 29, 1971, he sent a message to the UNHCR headquarters in Geneva.

As per the UNHCR ‘The State of the World Refugees-2000’ report, Hordijk told the world body that within a month, nearly one million refugees had entered India, fleeing the military repression in East Pakistan. “By the end of May, the average daily influx into India was over 100,000 and had reached a total of almost four million,” the report says. Indian official reports put the daily arrivals at about 10,000-50,000 refugees.

Pushpesh Pant, historian and author, says that in 1971 India’s economy was at the verge of collapse due to the burden of the refugees. “In particular, the state of West Bengal, which had received the largest chunk of refugees, was under tremendous pressure.”

The government had to issue a special postal stamp to raise funds for the refugees. Pant, who was teaching in the Delhi university then, remembers how people called conjunctivitis the Bangladeshi eye disease, as it was first spotted in a refugee camp. “However, despite this and other social tensions, there was huge sympathy and goodwill for the refugees across India,” he recalls.

On the political front, G Parthasarthy, the former diplomat who was posted in Moscow then, says India had taken a firm stand that at no cost it would take refugees permanently. “This was also partly done to put pressure on the world community so that they address the root cause of the problem – Pakistan,” he told Governance Now.

Bangladesh recognises that Indira Gandhi’s repeated remark that “the refugees would be sent back to their homes” had contributed immensely to the consolidation of Bangladesh nationalism and become a rallying point for the nascent nation that was to emerge soon.

The stories of torture, killings and rape by the Pakistan army narrated by the refugees were heartrending. However, a world polarised as it was between two big powers, the USA and the USSR, kept mum on India’s woes. Some countries took it as part of the unending Indo-Pak sibling rivalry and offered just lip service and some doles.

As soon as the first batch of refugees had arrived, the Indian leadership had sensed the lurking danger of the refugee buildup and begun preparing for a long haul including the possibility of a war with Pakistan.

In April 1971, Vijay Dhar was 30-year-old when his father DP Dhar, Indian ambassador in Moscow, was asked to quickly seal a treaty with the USSR that he had been discussing for too long. Vijay recalls how his uncle, foreign secretary Triloki Nath Kaul, had air-dashed to Moscow to finalise the India-Russia Friendship Treaty. “I had no idea that it will turn out to be the most important piece of treaty for us in the coming months,” he recalls.

Today analysts believe that this treaty had enabled Russia to mobilise its naval fleet in the Bay of Bengal as counter to the American 7th fleet, which could never come close to Indian shores. The Nixon regime wanted to bully India with its military might to give up the war with Pakistan. Russians, Dhar claims, were reluctant initially. “My father asked them point blank as why they were afraid of standing up to the Americans.”

Vijay Dhar had picked up some anecdotes from the conversation between his father and uncle, two key strategists of prime minister Indira Gandhi during those years. He recalls one: “My father and uncle would communicate in Kashmiri during the crucial and final round of negotiations on the Treaty. Initially, the Russians looked blank. But soon it was the turn of the Indians to get a surprise – the Russians had managed to get a Kashmiri interpreter!”

The refugees kept pouring in while US president Richard Nixon and his secretary of state Henry Kissinger were only thinking of how to save Pakistan. This was despite the US ambassador in New Delhi sending them this message in June: “The number of refugees is now 5.4 million and that rate of flow is increasing. This should be evidence enough that no matter what noises (Pakistani) president Yahya may make about restoration of normalcy, he has not yet done anything to effectively impede reign of terror and brutality of the Pakistan army, the root cause of the refugee exodus.”

A desperate and angry Indira Gandhi had, in a letter, told Nixon about the “carnage in East Bengal” and the flood of refugees burdening India. New Delhi told Americans that it was even contemplating training some of the refugees for guerrilla warfare against the Pakistani army. On hearing this, Nixon threatened to cut off economic aid to India!

Parthasarathy, however, says there was a wider appreciation of the refugee problem in the world. The aid for refugees had started pouring in from all over the world. “Though politically the US did not support India, it sent in a token aid for the refugees.”

The UNHCR has listed this as the world’s biggest movement of refugees in the second half of the 20th century. The Indian government had fixed rations for refugee. Each adult was given 300 grams of rice, 100 grams of wheat flour, 100 grams of pulses, 25 grams of edible oil and 25 grams of sugar per day, and half of this quantity for children. They were also given cash for daily expenses.

Left alone to cope with the mess created by Pakistan, India charted its own course and began preparing for an eventuality. Against all calculations, In December 1971, India fought a war with Pakistan; dealt it a humiliating defeat and kept its word to the refugees that they will be sent back “with honour” to their home – now Bangladesh. Some 6.8 million returned within two months of the end of the war while the last batch of 3,869 refugees left on March 25, 1972.

On December 16, the report of Pakistani army commander General Niazi’s surrender had first reached Delhi. Dhar recalls, “There was huge excitement in the war room where army chief General SFJ Manakshaw, PM’s principal secretary PN Haksar and DP Dhar were sitting.” They rushed to convey the news to Indira Gandhi, who broke it to parliament.

Dhar recalls the tense moments for all the PM’s war room managers for the next 24 hours as there was no confirmation of the surrender of one lakh Pakistanis. “In those days communications were poor and we had lost the link with the field. Immediately a senior General was sent to Dhaka,” he recalls.

What should be the take for Europe from the Indian story? According to Pushpesh Pant, India was bold enough to address the root cause of the problem and go to war for it, while the West today is not even ready to understand the root cause of the refugee influx at its doorsteps.

“The root cause of violence in Syria is the oil-rich Arab countries, mainly Saudi Arabia.” He says that the Saudi regime is the most “dogmatic, intolerant, uncivilised and least democratic”, and it sponsors what is seen as Islamic terrorism and Wahabism across the world.

“The irony is that Saudi Arabia is protected by the USA, and it is America which should be held responsible for destabilising more liberal countries in the Middle East and the Gulf.”

Pant says it is difficult for the Muslim refugees flocking to Europe to mingle with the society in their new countries. ''They will end up as cheap labour and live in ghettos and the social tension is inevitable,’’ he said.

As against this, India had housed the refugees in camps and provided facilities. They would be reminded of their homes and made to feel like guests. ‘‘Had we not done it, the refugees would have ended as cheap labour and created social unrest across India,’’ Pant said.

Despite a groundswell of sympathy for the Bangladeshi refugees, the situation was fraught with communal tension. Parthasarathy recalls DP Dhar’s admission that not allowing the anger of the early refugees – who were all Hindus and were persecuted by Muslims (Pakistani army) spill into the Indian society and cause communal tension was a huge challenge. “Pakistani forces had targeted Hindus believing that their votes had led to the victory of the Awami League. However, later they let loose their rein on terror on all and triggering the Muslim exodus.”

Indian refugees’ crisis had ended on a happy note – the creation of a new nation on the world map, Bangladesh, and breaking of a myth that only religion binds people of a nation. But is the West only interested in using refugees as cheap labour or is ready to take bold initiatives and make sacrifices like India did to teach a lesson to those responsible for the plight of refugees?

[email protected]

(The article appears in the October 1-15, 2015 issue)