A programme brings communities together to talk about public health services in their regions via public dialogue with government officials

In Lalheri village in Punjab’s Ludhiana district, groups of men and women from Hambran, Sidhwan, Ghalib, Manewal, Lubnagarh, Arain and other nearby villages have gathered in a hotel and occupy the seats in a hall for public dialogue. They are people who work as accredited social health activists (ASHAs), auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs) and gram panchayat members. They have gathered for a Jan Samwad, public dialogue with government officials.

The discussion begins with an anganwadi worker from Kaddon village. Raj Rani complains about various problems she faces in delivering the services. “We have not yet received funds for the construction of an anganwadi building. Kids have to go to a nearby gurudwara for drinking water,” she says.

Jaspal Singh, a panchayat member of Goh village, expresses concerns about difficulties in getting birth certificates. “The sub-centre is extremely far from the village. The anganwadi is in a rundown condition. There is no furniture for kids,” he further complains.

From Salaudi village, anganwadi worker Ranbeer Kaur laments, “There is no electricity and water supply in the anganwadi. The fund received by the community is not enough to address the infrastructure problem.”

The list of grievances grows further in front of the health department’s civil surgeon Rajiv Bhalla and the child development project officer (CDPO), Khanna town, Ludhiana, Sarabjit Kaur.

It is the first ever Jan Samwad in Ludhiana, under the Community Action for Health (CAH) programme, earlier known as community-based monitoring and planning under the national health mission. The programme engages people from a particular village to give feedback on the quality of healthcare in their area.

By the people, for the people

In Punjab, the CAH started on a pilot mode in Ropar block in 2013. “Reports were submitted to the state government and it was stressed to expand it in the entire state but that never happened,” says Dr Arvinder Singh Nagpal, the coordinator of the district level NGO working with the government on CAH.

The programme was once again geared up in 2016 and now it is implemented in 11 districts of Punjab.

Prior to Punjab, the Population Foundation of India, the health ministry-appointed advisory group on the community action (AGCA), started the pilot phase between 2007 and 2009 in Assam, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu.

Today, it is implemented in 353 districts of 22 states. “The CAH started way back in 2005 when the government launched the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM),” says Bijit Roy, team leader, AGCA. “In 2007-09, its implementation began on ground. Thereafter, it remained inactive till 2013. In 2014, it finally gained pace and is still in its nascent stage.”

It functions at three levels – first, regular reporting from the field, second, pre-audit surveys and third is people’s feedback and participation in Jan Samwad.

“The foremost criterion is to raise awareness about different roles of health providers and apprise villagers about their basic health entitlements. They have to monitor health services at community level, identify gaps at local level and then finally get in dialogue with service providers. It is possible by strengthening the village health, sanitation and nutrition committee (VHSNC) and Rogi Kalyan Samiti that functions at the village level,” says Roy.

The VHSNC in Ludhiana comprises gram panchayat members, ASHAs, anganwadi workers or ANMs and other representatives from community-based organisations. They address service gaps in sub-health centres and anganwadis, and have to report incidences of denial of services and non-utilisation of funds. The committee gets Rs 10,000 annually as an untied fund from the government. There are 12,956 such committees active in Punjab.

“By highlighting these obstacles, a sense of accountability is created not only among ASHAs, ANMs and gram panchayat members but also among senior officials,” says Daman Ahuja, programme manager, AGCA.

Preparing report cards

Gaps in the healthcare are identified through the preparation of the village health report card. It is done before issues are raised in the Jan Samwad. The report card is prepared through discussions with pregnant/lactating mothers and others who are availing different health services under government programmes.

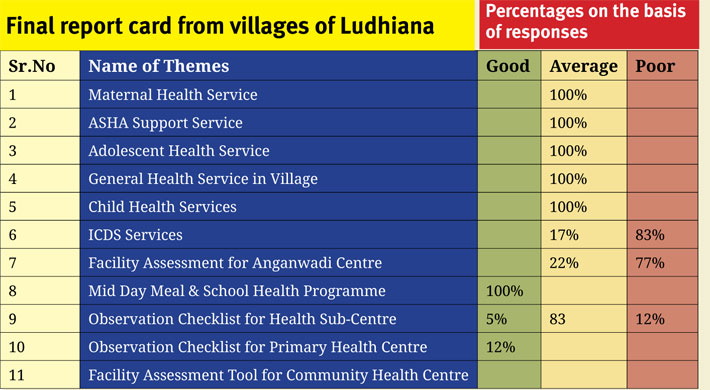

“There are basic questions in the report card like whether PHCs open on time, whether doctors are available or not and availability of medicines,” says Roy. Questions are divided under 11 themes – maternal health service, ASHA support system, general health service in village, child health services, adolescent health services, ICDS, facilities in anganwadi centre, school health programme and midday meal, observation checklist for health sub-centre and primary health centre, and facility assessment tool for community healthcentre.

Apart from this, a sub-health centre report card is also prepared based on direct observations related to the facilities in the sub-health centre.

The views shared by the respondents are recorded in the specified format. Three colours are used to rate the services as good (green), average (yellow) and poor (red). The collation criteria are – if the number of green tick mark is more than 75 percent and if the quality of healthcare service is rated as good. But if the green response is somewhere between 50 to 74 percent, services are rated as average. Less than 50 percent of green tick marks are put under the red category.

In this Jan Samwad, the state-level NGO along with district-level NGO shared the report card. It was found that maternal health services, ASHA support services, adolescent health services, general health services and child health services were average. On the other hand, ICDS services and facility assessment for anganwadi centres were in poor state while midday meal and school health programme were in a good state.

In Bihar, villages like Gambhri, Mananbhiga, Malhari, Imamganj and Khaira have shown remarkable changes through this programme. Primary additional health centres have been made functional, untied funds being used through awareness, functioning of Rogi Kalyan Samiti and demand for quality care.

Shortcomings

What was missing in Ludhiana was the village health plan. There wasn’t any discussion on charting an action plan. Before the Jan Samwad, the VHSNC prepares an annual village health plan, which cites reasons for gaps at the primary health centre, possible solutions, responsibilities and the required support that is lacking.

“It is the first Jan Samwad. Bringing together people is a tough task. Gradually, everything will fall into place,” says Monika Babbar, consultant, community participation, National Health Mission, Punjab.

At the Jan Samwad, many ASHAs and ANMs seem reluctant to talk about problems areas, probably fearing they might lose their job. Ahuja tried to boost the confidence of these foot soldiers to actively participate in the proceedings. He tells them how the health department alone cannot solve all problems and various other departments are equally responsible for lacunae. Still, it is important to talk about problems for attaining better solutions, he says.

“It is not a fault-finding process but a fact-finding activity,” says Ahuja.

archana@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the June 1-15, 2017 issue of Governance Now)