Living in geographical anomalies called enclaves along the Indo-Bangladesh border, they lived bereft of modern administration. After decades of struggle, people of 51 enclaves in India and 111 in Bangladesh get to chose their nationality

Agroup of seven crowd around a newspaper Abu Bakr Siddique is reading. The audience is eager to turn to the sports page, but Siddique is in a mood to tease them. Though impatient they humour him, till he gives in to curiosity. Soon, however, disappointment starts showing on their faces. The main news report on the page describes in detail the shocking 2-1 defeat India suffered at the hands of Bangladesh in the ODI cricket series. “What, India lost to Bangladesh?” says Siddique, who is equal parts dismayed and outraged. He kills a fly with a quick swat of his palm on his knee. It leaves a tiny stain on his new blue lungi (sarong), but he flings the tiny dead body with his forefinger and thumb as he would a carrom striker. Seated on a bamboo bench under a tin shed wearing a white vest rendered purple by overuse of fabric whitener, Siddique asks his companions what could have gone wrong.

IN PICS: 'Freedom movement' along India, Bangladesh border from today

'Freedom movement' along India, Bangladesh border from today - See more at: http://www.governancenow.com/news/regular-story/freedom-movement-india-bangladesh-border-day#sthash.I6WmnI16.dpuf

In the subcontinent where cricket is akin to religion, such a scene is ubiquitous. What makes this one rife with meaning is the location. Siddique was born and lives in Mashaldanga, about 50 km from Cooch Behar of West Bengal. Till a few weeks ago it was a Bangladeshi enclave – a village belonging to Bangladesh but surrounded on all sides by Indian territory. Born in this geographical anomaly locally called ‘chhit mahal’, Siddique – and thousands of others living in more than hundred such places along the India-Bangladesh border – had no identity and no basic rights, as both India and Bangladesh ignored them.

It should be normal for this group to celebrate the victory of the Bangladesh cricket team – technically speaking, they were Bangladeshis till the other day. Instead, a visibly sad Siddique tells Governance Now that he has always considered himself an Indian. The others nod.

On June 6, prime minister Narendra Modi and his Bangladeshi counterpart Sheikh Hasina exchanged instruments of ratification of the land boundary agreement. Under the deal, the two countries swapped 162 tiny enclaves dotting the border, thus undoing the anomaly and providing territorial contiguity – so that enclaves within India will now be governed by India. This spells a huge relief for the people living in these enclaves. The agreement gives them a choice: they can move to the other side, or stay on and become citizens of the new country. Siddique and his family say they are choosing the latter.

Siddique’s father Asgar Ali, who claims to be 105 years old, joins him and other villagers in the shade. He looks strong for his age but his responses, in Bhatiyali dialect of Bangla, are drawn out and slow. “Journalists have been coming here inquiring about our dilemma ever since I can remember. Finally, we have an identity,” he says above the humming sound of tractors ploughing the nearby fields. Two of his five daughters are married and settled in Indian enclaves in Bangladesh which are now part of the Bangladeshi territory. Most of his relatives are also there. All have gained identities. But at the cost of separation. They, however, have no regrets, for what they had to endure was worse than this temporary separation till their passports arrive. Now they look forward to amenities, especially healthcare and education, from a more answerable administration.

Siddique’s nephew Jahangir Alam, who studies in Class 8 in nearby Najirhat, says he had to conceal his identity as an enclave dweller to continue at the school. “If my teacher came to know I am from an enclave, I would have been thrown out of school.” It was the same for many other children. Typically, a relative or a friend from the ‘mainland’ would pose as the father of a child seeking admission to a school.

An enclave is a piece of land which is totally surrounded by a foreign territory.

Total number of enclaves in India and Bangladesh – 224 (including ‘counter enclaves’ and ‘counter-counter enclaves’).

There are 106 Indian enclaves belonging to the district of Cooch Behar, in Bangladesh. Of these, three are counter enclaves and one a counter-counter enclave. There are 92 Bangladeshi enclaves in India. Of these, 21 are counter enclaves.

Number of enclaves exchanged under the land boundary agreement – 162 (111 in Bangladesh, 51 in India).

The centre has announced a package of '3,008 crore to West Bengal to rehabilitate the Indian nationals who will come from Bangladesh once the enclaves and adverse possession areas are transferred.

Districts involved under the land boundary agreement

India: Cooch Behar, Jalpaiguri

Bangladesh: Lalmonirhat, Nilphamari, Kurigram, Panchagarh

Population in Bangladeshi enclaves in

India: 14,584

Going to Bangladesh: None

Population in Indian enclaves in

Bangladesh: 37,364

Going to India: 979

Alam, like most children of the enclave, was born at home. Even though fake identity papers were used to admit pregnant women in hospitals in ‘India’, if a woman went into labour at odd hours, absence of roads and lack of transport made it impossible for her to reach a hospital. As a result, infant mortality rates are high in Mashaldanga that is home to 3,870 people as per the Indo-Bangladesh census, 2011. Polio is the only vaccination which was administered by health workers, perhaps because of the high stress on its eradication. Otherwise, health workers hardly ventured inside these enclaves, as they were outside Indian jurisdiction.

The beginning and the end of enclaves are hard to fathom for an outsider. Villagers say that milestone-like markers which may lie hidden behind bushes indicate the enclave boundaries.

Villagers look on forlornly at the electric poles that run all around Mashaldanga but elude the enclave. A little distance away, a wire connects a house to an electricity pole. It belongs to the Das family that owns a seven-and-a-half bigha plot of land within the Mashaldanga enclave – but it is part of India, forming an enclave within an enclave or a counter enclave. The family has been living in a unique predicament: they live on Indian territory, they vote in elections, and yet they do not get many services of the state. For instance, they have no access to the integrated child development services (ICDS) scheme. Debashree Das, who is the only one at home, says the paddy they cultivate has to be transported in several instalments using a bicycle, as the roads cannot withstand the pressure of heavy vehicles.

In the pic: Asgar Ali gets an identity in the twilight days of his life

It has not been easy for enclave dwellers to find life partners too. Marrying an enclave dweller was considered a taboo in the neighbouring regions falling in India. Alam’s parents, for example, found the groom for his elder sister from the mainland – but only after offering a dowry of '1 lakh and a motorcycle. Still she has to face taunts from neighbours for her ‘chhit mahal’ background. Alam’s mother too is from the mainland. Why did she marry into the enclave? “There were no demands from the groom’s side. My family was too poor to give dowry,” she replies.

About 18 km away, in Poatur Kuthi enclave, men are conspicuous by their absence. Almost all of them sweat it out as labourers in various parts of India. Women here say they often land up in jail because police at the Cooch Behar railway station frequently check for suspicious elements and enclave people fail to produce any identity documents – they don’t have any. Rafikur Islam was once arrested and later ‘released’ into Bangladesh. “BSF people took me to a border point and just pushed me to the other side, telling me to run away.” He managed to find his way back.

Many earn their livelihood by working in the farmlands, but a majority of men still have to go far from home to earn – and travel without papers. In 2011, people from several enclaves came together in protest. “We put up an intense agitation in front of the [Cooch Behar] district magistrate’s office in 2011 after which police have stopped rounding people off from railway stations,” says septuagenarian Mansur Ali Miyan.

Still most men continue to take precaution, visit home rarely, and send their salaries through their employers. It is not only police but also criminals who have left them frightened

The rule of the jungle

In 2009, a woman was murdered and her body was dumped in Poatur Kuthi. Her parents maintained that she was an Indian citizen, but the West Bengal police refused to venture into the enclave. Finally, Udayan Guha, an influential political leader of the area had to intervene. “Three days later, I hired some men to move the body out of the enclave, after which the police took up the case,” says Guha, chief of Dinhata municipality and MLA, All India Forward Bloc (AIFB).

Mashaldanga people recall the fury they faced in 2000 after a Muslim boy eloped with a Hindu girl from a nearby Indian village. Suspecting that the boy was from Mashaldanga, people from the Indian village stormed Mashaldanga, set houses on fire and stole cattle. “The next day, police asked us to collect our cattle from a nearby place. When some of us went to collect cattle they were arrested and released only after the intervention of the Bharat Bangladesh enclave exchange coordination committee (BBEECC),” says Siddique.

Now they are formally in India, but it will take a while to wipe away years of hostility and mistrust. When Mashaldanga people took out a procession to celebrate the land boundary agreement, people from Monsob Seoraguri, an adjacent village which treats enclave dwellers as social outcasts, protested and a clash ensued. Policemen had to be posted to ensure peace.

Fear continues to stalk the enclaves, as criminals who found a safe haven in them are not about to give up easily. Some farmers admit, on condition of anonymity, that they lease their lands for illegal marijuana cultivation which fetches '50,000-60,000 per bigha, compared to '3,000 from rice cultivation. Farmers fear that criminal elements who used to cultivate marijuana may turn to land grabbing to continue the illegal business.

Amid all the adversities due to the absence of the state, enclave people have soldiered on. Though they have not been able to do anything about the lack of healthcare facilities, they have made ad-hoc arrangements on their own when it comes to education. In Poatur Kuthi, Mohiruddin Ali, Mansur Ali Miyan’s son, and his friends set up a rudimentary school a couple of years ago. It has no official recognition or support, and merely supplements formal schooling. “We give free tuition here,” says Ali walking through a stack of benches in the narrow corridor. The enclave also has a small madrasa.

As for electricity, some people like Saddam Miyan who could afford it have installed a solar panel at home. Mansur Ali Miyan has a smaller panel which barely lights bulbs in the evening. He cannot even run fans. His house, like a few others, has a clean and well-maintained washroom.

Enclave dwellers get their drinking water from tubewells only 25 feet deep (though fresh water aquifers are reached at 150 feet). Almost all of them have cell phones (of course, they have to go to shops in the Indian territory to recharge the phone batteries). Unlike Siddique, Saddam Miyan watched the India-Bangladesh cricket match at home on TV through a dish antenna.

The land ownership records of all residents of Poatur Kuthi had been issued by Rangpur district authorities in Bangladesh. Mansur Ali Miyan recalls paying taxes to Bangladesh when he was young. “Men from the Bangladeshi government used to come and collect taxes from us. It stopped after 1962,” he says. In the Indo-Bangladesh census of 2011, people living in these virtually no-man’s-lands got officially recognised as enclave dwellers.

Local politics

The BBEECC was formed in 1994 by Forward Bloc leader Dipak Sengupta and others to find a solution for the problems faced by enclaves. After his death, his son Diptiman Sengupta became the chief coordinator of BBEECC in 2008. Enclave dwellers organised under the banner of BBEECC to push for their rights. One representative from each enclave was chosen to avoid taking help from political parties, as they did not want the movement to be coloured by politics.

Forward Bloc was the only political party to advocate for the rights of enclave dwellers, says Biswanath Chakraborty, professor, political

science, Rabindra Bharati University. Though it was part of the CPM-led Left Front, which had given crucial outside support to UPA1, it could not do much to push for a land boundary pact.

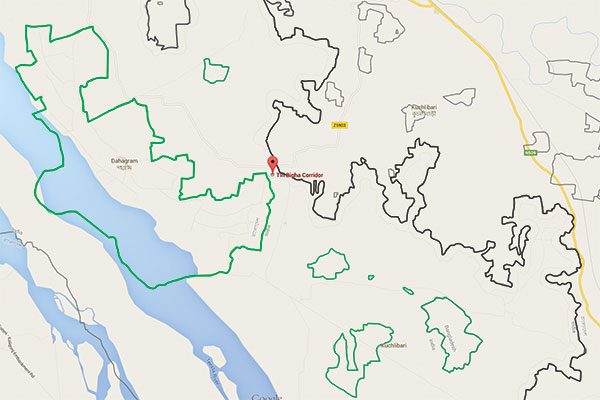

“There was no solution possible without exchange of land. We had discussed it with CPM many times. Though they agreed, they chose to keep silent on the Tin Bigha corridor. The corridor has been kept out of the agreement and, I am sure, it will cause much problem in the future,” says Udayan Guha of Forward Bloc. (Tin Bigha corridor is a strip of land belonging to India on the West Bengal-Bangladesh border. It was leased by India to Bangladesh in 2011 to enable people of Dahagram and Angarpota enclaves in India to travel to Bangladesh mainland).

As soon as the enclave became part of India, Trinamool Congress made a foray in the territory. In a single day the party’s Cooch Behar district president Rabindranath Ghosh visited three enclaves to congratulate people. He promised that the West Bengal government would provide them all facilities including schools, roads, electricity and drinking water.

But these services will take long. From July 6, a team of 75 officials began a census of the enclaves, also asking people if they want to remain in India or repatriate to Bangladesh. All of the Bangladeshi enclave dwellers in India have chosen to stay in India; whereas 979 people living in the Indian enclaves in Bangladesh have decided to come to India; majority of them are Hindus. This is in stark contrast to earlier estimates of about 13,000 people expected to come to India. Chakraborty says there are two probable reasons for such low turnout. “One very plausible explanation is the psychological bonding between man and land. People are reluctant to part with their land,” he says. The other reason, he says, could be people’s security concerns – misplaced or otherwise – in a Hindu-majority country.

July 31 is the day marked for the exchange of the enclaves. As per the agreement, which will be implemented in a phased manner over the next 11 months, India will hand over 51 enclaves, spread over 7,110 acres, to Bangladesh, and will receive 111 enclaves, spread over 17,160 acres in return. Between July 31 and June 30 next year the entire process, including physical exchange of enclaves and land parcels in adverse possession (the place that falls between de-jure and de-facto border) along with boundary demarcation, is expected to be completed. The passage of the enclave residents, arranged by the respective governments, is likely to take place by November 30, 2015.

Sandeep Salunke, who is inspector general, south Bengal frontier, Border Security Force (BSF), and also looks after north Bengal, says he has not received any formal instructions so far, but welcomes the agreement as “a clearly delineated border is always welcome and makes things easier at the operational level.”

Diptiman Sengupta strongly feels that identity is far more important than development. He has been demanding biometric identity proofs for the enclave citizens. “Development will come but first we need to recognise them as citizens. A voter ID card is for those above 18 years of age. We have a lot of population below that age who need an identity proof. We hope the biometric identification will start soon after July 31. We have a plenty of time to arrange for voter IDs before the 2016 assembly elections,” he says.

Politics of land boundary agreement

The BJP-led government in New Delhi took the initiative to seal the deal, though the party had earlier opposed such an arrangement. However, the move was not inspired by any vote-bank calculations, on either side of the border. The total population in the Indian enclaves is less than 40,000, and in the Bangladeshi enclaves it is estimated at about 15,000.

“Modi wants to position India as a global power so he wants to move away a little from nationalist sentiments,” says Chakraborty. “Modi is making an extra effort towards Bangladesh in order to isolate Pakistan. He is trying his best to unsettle Pakistan from south and southeast Asian politics. His foreign policy is directed heavily this way as is evident from his initiatives regarding Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka,” he adds. Chakraborty says perhaps BJP also feels that minority voters will come to place their confidence in it even if the rise of BJP in Bengal has been stemmed after the municipal corporation elections in April this year.

Chief minister Mamata Banerjee, who too had opposed the deal earlier as West Bengal will lose more land, has come around and supported the deal. “If we look at it from Banerjee’s perspective, her TMC (Trinamool Congress) badly needs the help of the central government, given the precarious state of finances. If TMC has good ties with the centre, the CBI investigation in the Saradha scam can also be ‘managed’,” says Chakraborty.

There is another reason why Banerjee needed to play along. On October 2 last year a blast ripped through the second floor of a building in Khagragarh area of Burdwan, killing two people. The building’s owner, Nurul Hasan Chowdhury, is a TMC leader, and he had even run a temporary party office during panchayat polls from this building. The National Investigation Agency (NIA) found that the accused, who stayed on the second floor, were members of the terror group Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen, Bangladesh (JMB), and were preparing improvised explosive devices for possible terror attacks in Bangladesh. The Sheikh Hasina government has been in the crosshairs of JMB. “Due to the Khagragarh incident Banerjee’s image has been heavily dented in the eyes of the Bangladeshi policymakers. The incident has also forced Banerjee to rethink the land boundary agreement,” says Chakraborty.

Om Prakash Mishra, general secretary of the state unit of Congress, says the TMC government’s U-turn on the deal was thanks to the centre’s compensation package of '3,008 crore. “The centre released part of the money even before the PM’s visit,” he says.

“The deal had been very much ready, all Modi had to do was to say ‘yes’. Earlier, he had opposed it; but he changed his mind as it is a recipe for success,” says Mishra. He says the Congress has supported the deal as it cannot afford to let the Hasina government get weakened. “There are many reform proposals and initiatives that we are not going to oppose. We want to show the contrast between the role of the Congress and the role of the BJP [when in opposition],” he adds.

Meanwhile, in this TMC stronghold, preparations are underway to take credit for the deal. In Poatur Kuthi, ahead of party leader Rabindranath Ghosh’s visit, youth is busy setting up a tent and fixing sound boxes.

Mansur Ali Miyan has been overseeing the work since morning. He takes a break and sits under the shade of a jackfruit tree beside a murky pond while his daughter-in-law stamps on the ripe paddy to separate the husk from the grain. He cradles a notebook in his hand in which he has documented the struggle of enclave dwellers. He shows a few pages.

In the early days after the partition, his entries talk of people getting killed by wild animals (Cooch Behar was largely forested back then). There are also entries about violent robberies he witnessed. And, of course, there are entries that bear witness to the travails and traumas of the life lived outside the modern state.

In an entry from December 2013 he has scribbled, “The land boundary bill introduced in parliament by foreign minister Salman Khurshid did not pass. The Hindus and Muslims in the enclaves of both countries do not even have the religious right to make pilgrimages or to go on Haj. Leaders of both countries, please lead us towards light!”

The last entry of the diary is in the first week of June. It reads, “Years of struggle has finally bore fruit. I am finally a citizen of India. I am eagerly waiting for the government to take over.”