Despite their high numbers, they are barely visible and budgets have not done enough for them

Land rights structurally escape women. This is a fundamental issue in understanding why women’s work as farmers is largely invisible. However, the large-scale migration of men towards pursuing other non-farm employment opportunities due to the worsening agrarian crisis has pushed more women into this sector. Work is not homogenous and neither are women or their work. Perceiving work through economic lens, the policy framework falls short in addressing the invisible and open unemployment of women along with increasing trends of feminisation in the sector. The first ask for women in the sector remains being identified as a ‘farmer’.

According to previous reports by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), the agrarian sector employs nearly 80 percent women workers. Despite such high numbers, both the sector and the macroeconomic policy framework are yet to recognise them as farmers. Moreover, 81 percent of the female agricultural labourers belong to dalit, adivasi and OBC communities (ILO, 2010). The largest share of casual and landless labourers also comes from these social groups. The burden of the agricultural debt has also inadvertently fallen upon women.

When unpacking schemes for women farmers, the Mahila Kisan Sashaktikaran Pariyojana (MKSP) is the only sub-programme under the Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana – National Rural Livelihood Mission (DAY-NRLM) particularly aimed at women farmers. The NRLM aims to reach out 8-9 crore rural poor households in an effort to organise 1 woman per household into self-help groups to take up organic farming in clusters. As per the ministry of rural development’s circular, “a total of 57,270 Mahila Kisan have been registered through 5,816 local groups for taking up organic farming”. The same circular also identifies nearly 14.03 lakh of women farmers under the State Rural Livelihoods Mission and MKSP. As one can see, women are at the centre of implementing the objectives of organic farming of the government. However, the total budgetary allocation for MKSP in 2018-19 (BE) was a mere Rs 1,000 crore. As MKSP is a sub-programme the allocations for 2019-20 (BE) are yet to be published. While the allocations for NRLM have increased over the years, increase in allocations for MKSP has yet to be realised effectively. In fact, the trends since 2014 show that not only does the policy framework suffers low levels of allocation and spending but also show how misplaced the government’s priorities continue to be in the agrarian sector with respect to women farmers. The sub-programme under NRLM for Mahila Kisan needs to be scaled up and backed with improved resource mobilisation plans, which may not be enough as work for women farmers also varies regionally. Moreover, transparency in the process of identifying and registering women farmers is crucial for better outcomes.

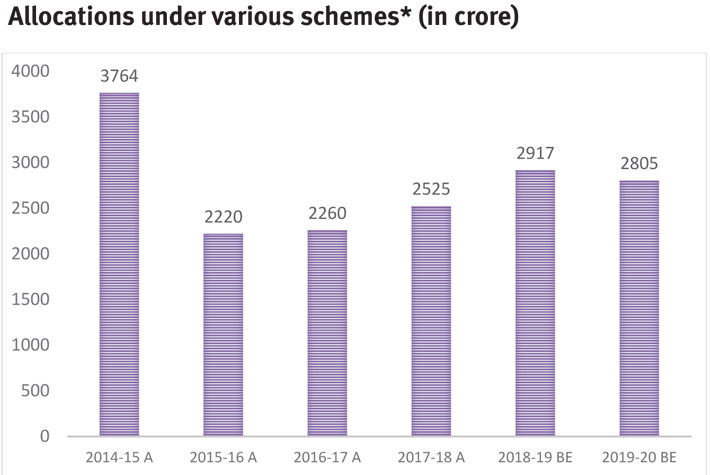

[Source: Compiled by CBGA from Union Budget documents, from various years]

As per the reply given by the ministry of agriculture in Lok Sabha on August 2, 2016, budgetary allocations for women farmers have been made at 30 percent on various schemes like Sub-Mission on Agriculture Mechanisation, National Food Security Mission, Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana, National Mission on Oilseeds and Oil Palm, Sub-Mission on Seed and Planting Material and Mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture (National Mission on Horticulture). The trend from 2014 shows that the fund utilisation for these schemes has systematically declined with marginal increases in allocation in years 2018-19 and 2019-20. It should be noted that the budget for the ministry of agriculture increased from Rs 57,600 crore in 2018-19 (BE) to Rs 1,40,764 crore in 2019-20 (BE). The total allocations for women farmers in 2018-19 (BE) under the above-mentioned schemes are 2 percent of the total expenditure under the ministry of agriculture for the same year. This amount is too little to provide coverage for the conservative number of 8-9 crore households.

The income guarantee scheme of Rs 6,000 per annum under the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Yojana for farmers owning less than 2 hectares of land announced in the interim budget is also outside the framework as most women in agriculture do not own land. In the absence of schemes designed especially for women farmers, there is little the government has been able to achieve to minimise gaps in land and asset ownership, wage gap, supportive infrastructure, access to credit, subsidised fertilizers, recognition to entitlements among others. n

Rai works with Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA), New Delhi.

(This article appears in the February 28, 2019 edition)