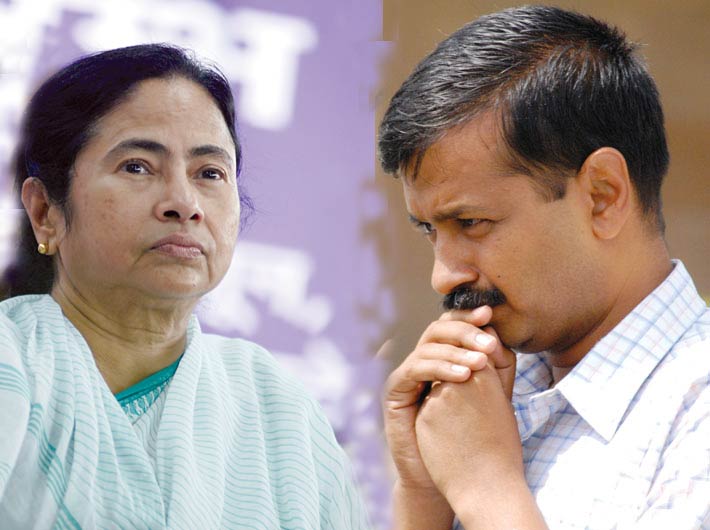

Hyperactive, populist and, well, somewhat anarchist, how similar is Kejriwal with Mamata?

They both arrived like whirlwinds after the latest round of state assembly elections in their respective states and governed with the panache of a tornado. And while anti-corruption activist and RTI campaigner Arvind Kejriwal jumped on to the political stage after spending time with his one-time mentor Anna Hazare during the Lokpal movement of 2011-12, his temperamental predecessor, so to speak, on the political dais, West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee, is reaching out to Hazare now.

So much so that after their meeting on February 18-19, questions are already being raised whether Banerjee’s TMC would find Kejriwal’s AAP as a natural ally.

While connecting with the people, spur of the moment decisions and their heart-in-opposition-even-in-governance mindset puts Kejriwal and Banerjee in the same basket – prompting marketing guru Suhel Seth to wonder on social media whether Banerjee is a “Kejriwal in a saree” and the latter “a Mamata Banerjee with a muffler” – they remain distinctly different as well. The biggest difference is that the uber-temperamental Banerjee is still at helm in Writers’ Building, Kolkata.

Kejriwal, the activist, the sensation and for many the ray of hope amid ruin and anarchy, stunned his opponents, pleasantly surprised his supporters and mildly amused the sceptics when he took oath for the chief minister’s office in Delhi on December 28, 2013. Forty-nine days later, he left many disappointed by resigning as chief minister amid pandemonium in the state assembly, raising many eyebrows and leaving behind an even more sharply divided AAP-BJP support base and #BhagodaKejri trending on twitter.

So how similar – or different – is Kejriwal from Banerjee, also well known for her hyperactive, populist and popular stances. More importantly, is there a lesson or two he can learn from her? (Recall that Banerjee, too, was somewhat of a motormouth, quote-a-minute CM in her first few months after she overthrew the Left Front regime).

Om Prakash Mishra, general secretary of West Bengal Congress and professor of international relations at Kolkata’s Jadavpur University, says that both leaders are “popular and populist” but the key distinction is that Banerjee never fought against corruption. Her “pet issue”, Mishra says, has always been political atrocity on civilians.

“The biggest corruption case (in Bengal) took place under her governance, when 30 lakh people were duped in a chit fund scam. She was also named in the scam. Despite that, Banerjee had the gall to name Ahmed Hassan Imran (editor of a Bangla daily that was previously owned by the scam-tainted Saradha group) as a Rajya Sabha nominee,” he says.

Another Kolkata-based political analyst (name withheld on request), who has seen Banerjee’s work from close quarters and is watching AAP and Kejriwal keenly, says AAP and TMC’s foundations are diverse. “AAP evolved out of civil society movement. The party has successfully highlighted political deficiencies but has not completely abandoned modalities,” he says. “Political parties bargain by negotiating. Though certain actions might look extremely high-pitched, they still constitute a regular part of political strategy.

“Banerjee can at times be very high-pitched, hyper and appear eccentric but she is very much within the political fold.”

Sabyasachi Basu Roy Chowdhury, vice-chancellor of Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata, and political commentator, says AAP offered a kind of deliberative democracy. “In a country like India, with conflicting and competing interests, interest articulation and aggregation” is the order of the day.

Stressing that Kejriwal and Banerjee are “two different idioms of politics that cannot be incorporated into each other, Chowdhury says, “Kejriwal has to be pragmatic; things cannot change all of a sudden.”

In words that could be deemed significant for both leaders, but more so for Kejriwal since Banerjee has won the mandate and somewhat settled down after the hyper-activity of the initial days, Chowdhury says, “Being in the opposition is completely different than being within the system. An alternate model has to be provided by taking into account the Indian scenario. Corruption is not the only issue. There are many issues intertwined within the system, which have to be contextualized.”

But Bengal Congress’s Mishra says, “Mamata is in public domain since the 1980s and has been a central minister four times before taking on the Left Front government. She has failed five times before registering success. Her success is directly proportional to the repudiation of her stand against the Congress. Kejriwal (in contrast) registered his political party only in 2012 backed by the civil society.”

Any parallel between Banerjee and Kejriwal, thus, is “misplaced”, Mishra says.