A look at how Singapore became the tiger of southeast Asia and what India can learn from a city-state of 5.56 million people

The Singapore story is essentially a telling in resilience and collective will. If an analogy between the island-nation and an individual could be drawn, its life-narrative would find place in the annals of history as one of the most inspiring rags-to-riches story. A newly independent Singapore in 1965 with S$3 billion GDP grew to 15 times its size in 1997 to S$46 billion and to its present size of S$421 billion in 2013. Its landmass is roughly only 3.5 times the size of Washington DC.

The Singapore we see today – the towering 4,300 high-rises, swanky ports, an urbane, literate population and a GDP equal to the nations of western Europe – is a compressed rapid growth of about 30 years. It is in stark contrast to the Singapore of 1963, when a British politician had called it a “pestilential and immoral cesspool”. The city-state has charted an unfamiliar story of successfully emerging from typical post-colonial grappling with ruins left behind by the European empire – poverty, unemployment and low self-esteem.

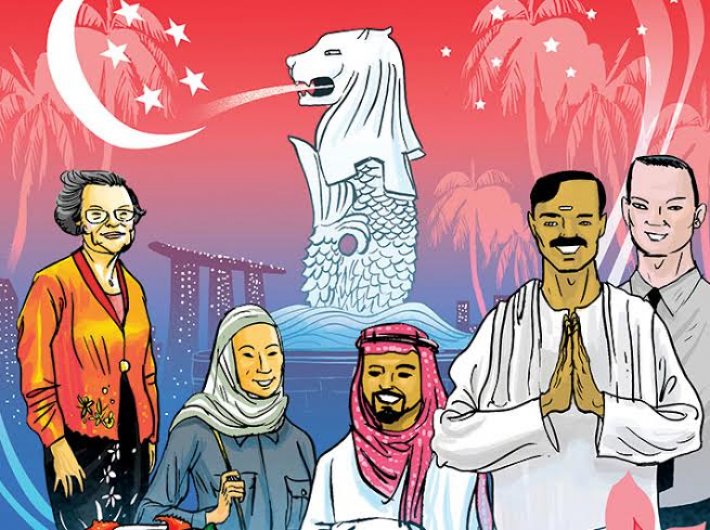

A melting pot

Singapore became a trading post when Stamford Raffles of the East India Company in 1819 landed on an island of about 1,000 Orang Laut, perhaps the only inhabitants who can claim original occupancy of the place apart from a section of Malays. The British-occupied state adopted a free trade policy with no restriction on immigration unlike the surrounding Dutch-controlled ports. By 1827, Chinese formed the majority of the immigrants followed by a kaleidoscope of people as diverse as Malays, Peranakans, Indians, Arabs, Jews, Armenians, Eurasians and Europeans. Over a period of 40 years, Indians became the second largest community (now they form the third largest group) with the bulk made of south Indian labourers in dockyards, railways and rubber plantations followed by Sikh, Gujarati, Sindhi merchants and Chettiar moneylenders. However, by the beginning of the next century, Indians were English-educated and took up white collar jobs, forming an important constituent of Singapore’s evolving hybrid culture. Thus was formed a multicultural mosaic of identities impregnated with many world civilisations – Indian, Chinese, Middle Eastern, European, etc.

The present multiculturalism of the city-state is perhaps best exemplified through its gastronomical assortments – the famous chilli crab is a mix of Chinese bean paste, Malay chilli, western tomato sauce and Sri Lankan crabs, and Jawi Peranakan (descendants of Muslim Indian/Arab men who were mostly spice traders and local Malay women) cuisine has a unique blend of Malay herbs and Indian spices.

Freedom at last

Except for a brief occupation by the Japanese forces (1942-45) during World War II, Singapore was under British occupation with increasing levels of self-governance, till it joined the Federation of Malaya in 1963 to form Malaysia, and subsequently established itself as an independent nation in 1965 – for 146 years before that Singapore was only an outpost of the British Raj.

Like India – and unlike China or Vietnam – the political emancipation of Singapore did not see any revolutionary transformation in society or its people. This was perhaps because its first prime minister Lee Kuan Yew and India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru were both children of the European empire. Educated in Britain, both adopted the Westminster form of governance for their respective countries, retaining the English common law, the civil services. (In fact, Lee was much influenced by Nehru, and The Discovery of India written by Nehru, was one of his favourite books.) Moreover, like India, Singapore has been able to articulate a mode of politics which is accommodating of its many discontinuities in race, class, religion and caste.

Lee came to power through the first general elections of the self-governing state of Singapore within the British empire in 1959. Possessing no natural resources of its own, Singapore was important only as an entrepot for trading goods. With the subsequent withdrawal of British bases (British military spending was about 20 percent of Singapore’s GDP and provided 70,000 jobs, directly and indirectly), Singapore was left in a state of virtual collapse. Lee, apart from the tough work of negotiating severe employment crisis, housing problems and social unrest, was also faced with the problem of nation building and securing the loyalty of very dissimilar peoples. In his memoirs, The Singapore Story, Lee writes, “I have not seen a book on how to build a nation out of a disparate collection of immigrants from China, Britain, India and the Dutch East Indies…”

Sighting the future

Owing to the lack of a common market with Malaysia and termination of trade with Indonesia, Singapore had to quickly industrialise without the comfort of having friendly neighbours. Lee did an Israel, so to speak, by leapfrogging trade with the region and preparing a market for Europe, the US and Japan. Since human resource was Singapore’s only strength, Lee focused on rendering First World standards of service which would come to be known for its efficiency and organisation. Also, locally assembled cars, refrigerators, televisions, radios and other goods were aggressively protected (such protectionism was, however, phased out by 1975). Secondly, Lee concentrated on developing the tourism industry which would be labour-intensive, absorbing people left jobless by the British withdrawal with little capital investment requirements.

Another important strategy used by the Lee regime for stabilising the economy was converting two naval dockyards in Sembawang left by the British for civilian use. Hon Sui Sen, former Singaporean finance minister, put all real estate to economic use; so much so that by 1971, in the words of Lee, “no land or building was left idle or derelict”.

The Singaporean government initially had a tough time attracting foreign investment. In 1961, the Economic Development Board (EDB) was set up on the advice of Albert Winsemius, the Dutch economic adviser to Lee who played an important role in the growth story of the island. The EDB, which was a one-stop agency for investors, precluded the necessity of dealing with multiple ministries. The EDB would sometimes make 40-50 calls to international investors before even one of them visited Singapore. The break came with Texas Instruments setting up an assembling factory for semi-conductors in 1968 followed by its competitor Hewlett-Packard. A serendipitous occurrence during the time was the Maoist Cultural Revolution, which saw investors avoiding Taiwan and Hong Kong, both perceived to be close to China, and flocking to Singapore.

In the late 1970s, General Electric set up six facilities for its range of products, including circuit breakers and electric motors, and was the largest single employer in the city-state. By 1997, the US had become the biggest foreign investor in Singapore with nearly 200 manufacturing companies and worth over S$19 billion investments at book value. This was followed by Japan, which also by that time had become the largest investor in manufacturing, especially setting up middle-level technology facilities, in east Asia. The British came in to manufacture high-value added products like pharmaceuticals for their markets in Asia. Thus was established one of the biggest manufacturing hubs in Asia. The government started new industries like National Iron and Steel Mills, Development Bank of Singapore, the Insurance Company of Singapore, Singapore Airlines and Singapore Petroleum Company.

In a similarly fascinating story of Singapore becoming the financial hub of southeast Asia, Winsemius, with the help of a banker-friend in London, fitted the city-state in a slot which would complete the 24-hour round-the-world service in money and banking. The Zurich-Frankfurt-London-New York-San Francisco financial circuit had a gap between San Francisco closing and Zurich opening. Singapore took over before San Francisco closed and Zurich opened. It gradually built its credibility where the risks of systemic failure – lack of supervision of banks, security houses, inefficient officers – were minimised. The offshore Asian dollar market was initially modest but because it fulfilled a great market need, by 1997 it exceeded US$500 billion, marking Singapore as one of the larger financial centres of the world. In the 1990s, Singapore’s foreign exchange market was the fourth largest after London, New York and marginally behind Tokyo. During the East Asian crisis of 1997 when the Thai Baht was devalued and stock markets, currencies and economies faltered, Singapore banks stood strong.

A room with a view

Another remarkable success in the Singapore story is the low-cost housing scheme. The Housing and Development Board (HDB) was set up in 1960 to build houses for workers. In 1968, workers were allowed to use their accumulated central provident fund to pay the 20 percent down payment and the rest in monthly instalments over the next 20 years for occupancy of the HDB flats. In 1996, 91 percent of the 7,25,000 HDB flats were owner-occupied. Breaking the convention of racial segregation of residential spaces, these HDB flats made racial mixing inevitable. Racial quotas were introduced in public housing in 1989 and in 2010 HDB quotas were also introduced for permanent residents (a visa status where non-citizens can live indefinitely).

Lee narrates in his memoirs some interesting anecdotes of comic adjustments that people had to make in these HDB high-rises: several farmers who could not bear to part with their pigs were seen coaxing them up the stairs, the Malays planted vegetables around the buildings like they were used to in their kampongs while the Chinese, Malays and Indians refused to take the lifts because they were afraid.

Through a remarkable plan of making EDB and HDB work together, Lee set aside land in the housing estates for clean industries which could employ housewives and women. In 1971, Phillips built its first factory in Toa Payoh, followed by Hewlett Packard, Compaq, Apple, Motorola, Seagate, Hitachi, Mitsubishi Aiwa and Siemens, producing computer peripherals and electronics and employing 1,50,000 people living nearby.

The future is here

Lee stepped down as the prime minister in 1990 to be succeeded by Goh Chok Tong and subsequently by Lee Hsien Loong, son of the first prime minister and the present PM of Singapore. People’s Action Party (PAP) has dominated every general election since Lee took over in 1959. Critics have argued that despite its Westminster pedigree, Singapore is essentially a one-party state where competing opposition parties have been treated unfairly.

Singapore is hardly immune to social conflicts and economic challenges. The slowing growth in emerging markets, especially Asia, the rising labour costs, increasing restrictions on foreign workers and an ageing population has dented the export demand. In the first quarter of 2013, manufacturing, driven particularly by higher electronics and biomedical production, fell by 6.7 percent. But there has been an uptick in the second quarter of 2013, growing 3.68 percent year-on-year. The government earmarked about $4 billion to aid firms in investing more in enhancing productivity to counter labour supply restrictions.

One of the most challenging problems of this island-country is that of dealing with an ageing population while at the same time managing immigration. In 2012, the first cohort of baby boomers turned 65 and by 2030 a quarter of the current citizen population would have reached retirement age. From 2020 onwards, this trend will become starker as the number of working-age population will decline – Singapore with its low birth rate cannot quickly replace its retiring population. To address this concern, the government presented a Population White Paper, which proposes to increase the population to 6.5-6.8 million by 2030 from the current 5.3 million. The paper suggests ways to regulate the intake of new Singaporean citizens and permanent residents. The proposal has evoked protests with fears of the negative impact on house prices, wages, infrastructure and a dilution of the ‘Singapore identity’.

Though the island was built with help from foreign workers and migrants, hostility against new immigrants and race clashes has required attention. There were two clashes in July and September 1964 between Chinese and Malay groups and one in 1969. The Little India riot in December 2013 reflected the anger of Indian migrant workers about their working conditions.

The government has devised various methods through the years to manage high immigration. Whereas in 1971, work permit was given even to non-citizens, in 1987 the Lee government levied a fee payable by employer for every foreign worker employed and to have a ‘dependency ceiling’ restricting the numbers of foreign workers for an employer. Immigrants are divided into foreign talent (foreigners with professional qualifications working at the higher-end of the Singapore economy) and foreign workers (unskilled and semi-skilled labour working in manufacturing, shipyards and construction sites) by the government. In 1989, it was announced that the government would over the long term encourage selective immigration of foreign talent who would be given permanent residency. To achieve its objective of developing Singapore into a talent capital of the global economy, Singapore has had to walk a tight-rope between attracting foreign talent and restricting foreign workers.

To deal with the immigration reality, there have been several government programmes promoting the integration of the host community with immigrants. Singapore’s national integration council was established in 2009 to promote national solidarity, and a US$7.95 million community integration fund was created to foster interaction between Singaporeans and immigrants. Additionally, in 2011 Singapore citizenship journey—a programme for orienting new citizens—was launched.

Around 40 percent of Singapore’s 5.4 million people are foreigners. Immigration has continued to be a major issue affecting both the general and the presidential elections in 2011. Beginning of this month, the government introduced new labour laws which will make it more difficult for foreigners to get jobs. The companies now have to advertise jobs to Singaporean citizens and permanent residents first and hold it for at least two weeks before it is opened for others. Some experts argue that this might prove detrimental for the economy which is built on its migrant population and finding the right skill-sets across a diverse range of jobs. However, the long-term impact of such a law is yet to be seen.

Singapore has carved a niche for itself in the global order which is unlikely to be threatened by any violent anarchy. However, what it does need urgently is a reconfiguration of national consensus wherein cultural tensions unlikely to go away anytime soon, can be negotiated better.

The story appeared in the August 16-31, 2014 issue of the magazine. More stories on this theme coming soon on our site.