Even though a number of studies highlight alarming levels of mercury emission in India, the government is still not ready with a national policy to address the issue

Many of us have fond childhood memories of playing with droplets of mercury spilled out of a broken thermometer. A dark silver-coloured shiny liquid was a plaything for kids and perhaps still is, but in reality it is quite a dangerous curiosity. Unaware of the toxicity that mercury contains, many continue to mishandle mercury thermometers at homes and clinics, the consequences of which are not pleasant. Joint and body pain, nausea, skin discolouration, difficulty in speaking and blurred vision are some of the symptoms of mercury poisoning in the human body.

But in the past, not just individuals but manufacturers of mercury-added clinical products too have mishandled mercury, causing major loss to human health and environment. The now defunct thermometer factory of Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL) in Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu, is one tragic example. Around early 2000s, a number of workers at the factory began complaining of kidney-related ailments. Soon, in 2001, public interest groups accused the company of disposing off mercury waste without following proper procedures, thus contaminating groundwater and forest area. It was also alleged that the company made its workers handle mercury without any protective gear.

After 15 years, the company was made to compensate its ex-workers. However, it seems that the Tamil Nadu pollution control board (TNPCB) hasn’t learned any lessons from the incident. “The contaminated site comes under the forest area, but the state body had set residential standards of mercury clean-up in the area at 20-25 mg/kg. They claim it is adequate to protect residents, but what about the forests? More stringent standards have to be evolved – at 6.6 mg/kg,” says Nityanand Jayaraman, a social activist associated with NGO Jhatkaa. A senior official at TNPCB, however, says that the clean-up activity hasn’t started yet and the standards to be applied are still under consideration.

In India, around 21 tonnes of mercury is used annually in manufacturing mercury-based thermometers, as per data provided by Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) for 2011-13. “Yet, there is no system to treat mercury-contained clinical devices separately in India,” says Piyush Mohapatra, programme coordinator, environment equity and justice programme, Toxics Link, a Delhi-based non-profit organisation working on environmental issues.

Mercury-added consumer products, however, contribute only a small portion in the overall pollution caused by mercury in India. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) data of 2005, industrial plants involved in burning of coal are primarily responsible for polluting the environment – with 87 percent of total mercury emissions. In another study, CSE found 290 tonnes of mercury being emitted by the industrial sector during 2011-12.

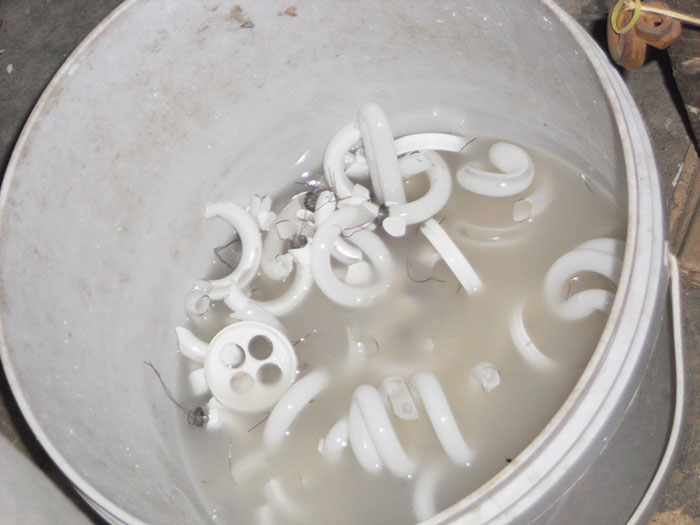

Photos Courtesy: TOXICS LINK

CFL bulbs containing mercury being disposed of and treated in the informal sector.

The IEA Clean Coal Centre, an organisation that carries out research on clean and efficient use of coal worldwide, found India to be the second largest polluter of mercury in the world after China in a 2012 study. With the “limited” data available on mercury emissions in India, the study found that 8.83 percent of the global total was emitted from here.

As such, there is no clear data by the government on the total mercury emission from various sectors.

“If no action is taken, emissions from India could increase by 44 percent within the next decade, the largest increase being in the coal combustion sector,” Lesley Sloss, a member of IEA Clean Coal Centre, has said in her 2012 report on mercury emissions from India and southeast Asia.

In 2014, India became a member of the UNEP-led Minamata Convention, along with 127 other member countries. The convention, aimed to regulate and phase out mercury usage around the world, was named after a city in Japan. Minamata was affected by a disease caused by consumption of fishes containing high level of methylmercury, a more toxic element, all because of a chemical manufacturing company named Chisso that had been discharging its industrial waste containing mercury, directly into the Minamata Bay, from 1932 to 1968.

In India, a national action plan to ratify the convention is awaited. “The formulation of a plan would take another two years to get ready, since the government does not have a comprehensive inventory on mercury,” says an official from the ministry of environment, forest and climate change (MoEFCC). “If we have to take that as a bind upon us, we should know where we stand,” the official added.

Once ratified, India would be legally bound to follow the rules issued under the convention. So far, only 25 countries have ratified the convention. These countries would have to implement their policies to control and regulate mercury supply and trade, reduce usage of mercury, ban manufacturing of mercury-added products by 2020, reduce mercury emissions and releases, identify sites contaminated with mercury and deploy efficient technology for remediation, ensure safe handling of mercury waste and retire excess mercury for long-term storage, and constantly monitor the transportation of mercury within the country and at cross-borders.

The MoEFCC official adds that India would soon start mercury’s initial assessment, a UNEP project, which would help identify all the sectors using mercury and their rate of consumption and emission. The data would subsequently help the government to form policies to control mercury pollution in the country. “Once the assessment is done, we will be in a position to take a call on ratification of the Minamata Convention – whether we have to go with the deadline or opt for an exemption,” the official says.

Satish Sinha, associate director of Toxics Link, is worried about the deadline. If a national action plan is not submitted to UNEP before March 2017, he says, India would not be able to participate in its next conference in Geneva in June 2017. “It would be sad if India doesn’t participate as I believe India should be looking at a leadership role in the convention.” The MoEFCC official, however, was optimistic about India’s participation in next year’s conference.

Status check

In India, a major portion of mercury emission comes from burning of coal by industries, mainly coal-based power plants, gold mining plants and chlor-alkali plants, since mercury is a natural element of coal. Many studies have found that coal in India has a high amount of mercury, which is released into the environment through gases, ash and dust.

Jayshree Chemicals’ chlor alkali plant in Odisha is identified as a mercury contaminated site by CPCB. It released its mercury-contaminated waste into the nearby areas and the sludge close to the pond which is located in the bed of the Rushikulya river.

“From coal combustion, around 58 percent of mercury is released in gaseous form, 2.5 percent in particulate matter (PM), around 32.5 percent goes through ash while the remaining seven percent remains unaccounted for,” says Sanjeev Kanchan, deputy programme manager, sustainable industrialisation, CSE.

Moreover, the study by Lesley Sloss finds that Indian coal is particularly low grade, containing 35-45 percent of ash, and thus more coal is needed to be fired to produce power, in turn increasing the mercury emission.

The CSE’s Green Rating Project in 2015 had conducted a study on 47 coal-based power plants across the country. Its findings were alarming: 20 plants were discharging ash slurry, holding toxic heavy metals, directly into rivers and reservoirs, while nearly 60 percent of the plants analysed did not have effluent and sewage treatment plants. The study also found that only 50-60 percent of the 170 million-odd tonnes of fly ash generated by the sector was being “utilised” while the rest was dumped into poorly designed and maintained ash ponds, thus polluting land, air and water. In such cases, mercury transforms into methylmercury which then enters into our food chain, affecting us and other living beings.

In another CSE study conducted in 2012 in Sonbhadra district, Uttar Pradesh, average mercury content in 19 human blood samples was found to be six times the safe limit (5.8 ppb, as per the US Environmental Protection Agency) while drinking water was found unfit for consumption without treatment. Same was the case with Rohu fishes of Rihand reservoir. Mercury was present in all seven soil samples. In fact, the study found mercury level of 113.48 ppb – nearly 19 times the safe limit – in the blood sample of a resident of Khairahi village who used to eat fish two-three days in a week.

The problem is that there is no technology deployed by power plants to control mercury emission, and most of them do not even monitor the emissions constantly. It is because India, until December last year, did not have a standard set on mercury emission from power plants. MoEFCC notified the standard of 0.03 mg/Nm3 for mercury, on recommendation of the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). “Since there was no norm till now, industry didn’t bother to monitor and control mercury emission,” says Kanchan.

India also doesn’t have an adequate amount of coal washing technology which is used to reduce ash from coal by 10-30 percent. “We have less than one-third of the capacity required for coal washing in India. Since washed coal is expensive compared to raw coal, there are fewer buyers for it,” says Kanchan. As per the government data, production of washed coal was 6.011 million tonnes during 2014-15, down by 9.1 percent from 2013-14. The ministry of coal, however, plans to change this situation. “We are aiming to increase the capacity of washed coal to 112 million tonne by September 2017,” says DN Prasad, advisor (projects), ministry of coal.

As per the World Health Organisation (WHO), exposure to mercury, even in small amounts, may cause serious health problems to the development of foetus and in early stage of a child’s life. The toxic element, depending upon its exposure, may also affect the nervous, digestive and immune systems, and lungs, kidneys, skin and eyes.

“A significant investment of expertise, time and money in improving the existing emission inventories is needed to find suitable and viable options for mercury emission control in India,” says Kanchan.

Control mechanism

Some positive steps have been taken towards regulating mercury handling in the consumer sector. In April, MoEFCC revised the e-waste management rules to include compact fluorescent lamp (CFL) and other mercury containing lamps under its ambit for their safe collection, treatment and waste disposal. Mercury contained in CFL bulbs was so far dumped in the open since there were no regulations.

The new rules, to be effective from October 1, will also follow the European Union standard on mercury allowed in lamps, which is 2.5 mg for 26 watt of bulb; at present it is 5 mg. However, according to a Toxics Link study of 2011, average mercury content in CFL bulbs was found to be as much as 21.21 mg.

“There is an alternative available to these CFL bulbs that are light-emitting diode (LED) bulbs, which do not contain mercury. I don’t understand why the government is so reluctant to promote the mercury-free technology available in India,” says Sinha.

For industries, even though there is no mercury controlling technology adopted in India yet, there are other ways to reduce mercury emission – they can deploy existing technologies that control emissions of particulate matters (PM) and sulfur dioxide (SO2). This is because when coal is burned, mercury is emitted through PM and SO2 into the atmosphere. “Mercury controlling technology is very expensive. Indian power industry still can reduce mercury level to an extent by controlling PM and SO2 emissions. However, only a few coal-based power plants at present have flue gas desulfurization (FLD) technology that is used to control sulfur dioxide emission,” says Kanchan.

Now, it is to be seen how India formulates and implements its policy that would control mercury pollution, a danger created by large-scale industries followed by the informal sector. More importantly, awareness among the public and various stakeholders about dangers of mercury pollution is needed. “It’s high time the government understood that the cost of inaction would be much higher than the cost of action,” says Sinha.

taru@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the June 1-15, 2016 issue of Governance Now)