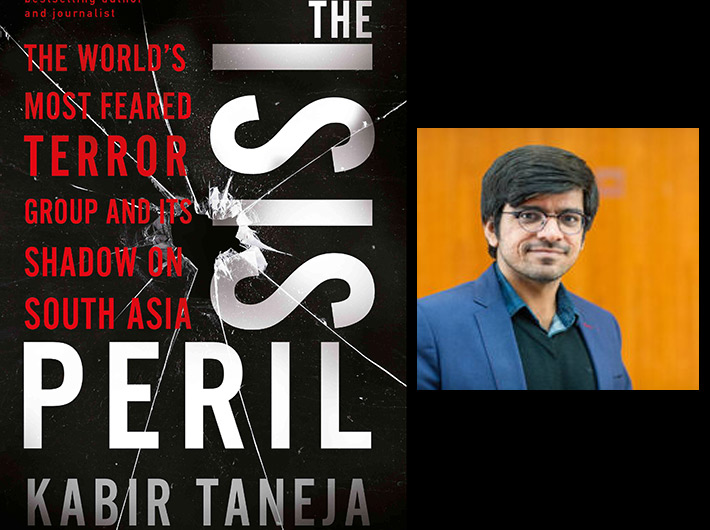

An excerpt from

The ISIS Peril: The World’s Most Feared Terror Group and Its Shadow on South Asia

By Kabir Taneja, Penguin

208 pages, Rs 499

The immediate threat from ISIS is not on the battlefield anymore, but in civilian spaces. The SDF [Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces] along with the few international aid organizations working on the ground have been left with the job of taking care of the land and people in a post-ISIS region, capacity that the Kurds-led group does not have. With hundreds of people living in makeshift camps, and many ISIS fighters being held in makeshift prisons, in close proximity with each other, there is complete confusion on how to handle these camps, who will pay for them and what to do with the ISIS fighters. In fact, the celebrations of an ISIS defeat at this rate could be short-lived, as the Kurds, who first took on the weight of actually defeating ISIS and now are having to host the stateless citizens of the caliphate may have no choice but to slowly release these radicalized people back into society. Most ISIS fighters in captivity would still be what they set out to be, those who believed in the caliphate and would still like to see it make a return. And considering the political landscape in both Syria and Iraq, many would also like to think that resurgence is fully plausible.

In mid-April, an activist group working in Syria said that ISIS in the central parts of the country killed more than sixty fighters supporting the Syrian government. While casualties were significant in number, this was not a one-off incident. ISIS has been active on both fronts despite their supposed defeat, and while their hierarchy has largely kept silent or is under complete hiding away from using communication tools and so on, the pro-ISIS narratives still maintain high visibility across the board.

Currently, the central Syrian region is acting as an excellent example of how not to approach the end of a terror group to make sure it does not have the intent or capabilities to restart in the near future. The challenges to defeating ISIS, fortunately or unfortunately, largely lie in Washington D.C. at the moment. Whether the world likes it or not, the de facto police of the world to its detractors, of whom there are plenty specifically in this region, US military deployed against ISIS is absolutely critical to manage the fallout of the caliphate, and to provide financial and military backup to the SDF which is the only organization on the ground currently looking to work with Western powers against ISIS.

However, this partnership is at a perilous stage itself as of December 2018. President Trump’s declaration of victory against ISIS was a precursor for a troops withdrawal. On 20 December 2018, Trump tweeted: ‘Getting out of Syria was no surprise. I’ve been campaigning on it for years, and six months ago, when I very publicly wanted to do it, I agreed to stay longer. Russia, Iran, Syria & others are the local enemy of ISIS. We were doing there work. Time to come home & rebuild. #MAGA.’ This abrupt withdrawal expectedly caused a flurry of concern at the Pentagon and US State Department, as both organizations, staffed with experts who have worked on the region for decades, rushed to control the damage such an abrupt move would cause. There are also indications that these decisions by the Trump administration were only found out most via his tweets, and not direct consultations.

One of the first casualties of this abrupt end to the US campaign against ISIS was Brett McGurk, the US special envoy for the global coalition to defeat ISIS. ‘The recent decision by the President came as a shock and was a complete reversal of policy. It left our coalition partners confused and our fighting partners bewildered with no plan in place or even considered thought as to consequences,’ McGurk said in an email he sent to his staff before resigning from his post.

McGurk and others working with partners on the Syrian front had painstakingly developed an ecosystem which would be capable and able to fight off both ISIS, and a resurgent ISIS in the future if the situation arises. The recalibration of the US anti-ISIS strategy by Trump significantly shortchanged this, by bringing down the number of US troops deployed to assist the likes of SDF to around 400, with half deployed around northeastern Syria and the other half in Al Tanf, a US military base on the Syria–Iraq border in the Homs governorate. Considering the scale of the conflict, and the fact that at a point of time Islamic State territorially was just about the same size as the UK, a residual force of 400 odd troops to back the SDF is the writing on the wall of a failed long-term policy of ensuring sustained stability.

However, a mere 400 troops expected to help maintain the sanctity of a sectarian fraught war zone is about the same as attempting to apply Band-Aid on a wound that requires reconstruction surgery. Why? Because ISIS has already proven to a certain degree that it is fairly proactive in conducting operations, not just in Syria and Iraq, but globally, and increasingly, in more countries.

In mid-April, ISIS claimed an attack in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a vast country in the centre of the African continent, declaring it the ‘Central African Province’ of a caliphate, which, as far as geography goes, does not exist anymore. The claim came after a gun battle between local soldiers and unidentified armed gunmen near the town of Beni. Between April 10–16, ISIS claimed attacks in ten countries, excluding Syria and Iraq, ranging from Pakistan and Russia to Afghanistan and Egypt. These went mostly under the radar as far as international Western media goes (even elsewhere, other than the media of the countries concerned) but they happened, and this uptick coincides with the increasing number of ISIS guerrilla attacks in Syria and Iraq as well.

Kabir Taneja is a researcher and writer based in New Delhi. He is currently a Fellow with the Observer Research Foundation (ORF). His work focuses on India's relations with the Middle East, specifically looking at the security dimensions raised by transnational jihadist groups. His byline and quotes appear regularly in national and international media.

[This excerpt is reproduced with permission of the publishers.]