There’s more than just lack of awareness to blame for the low rates.

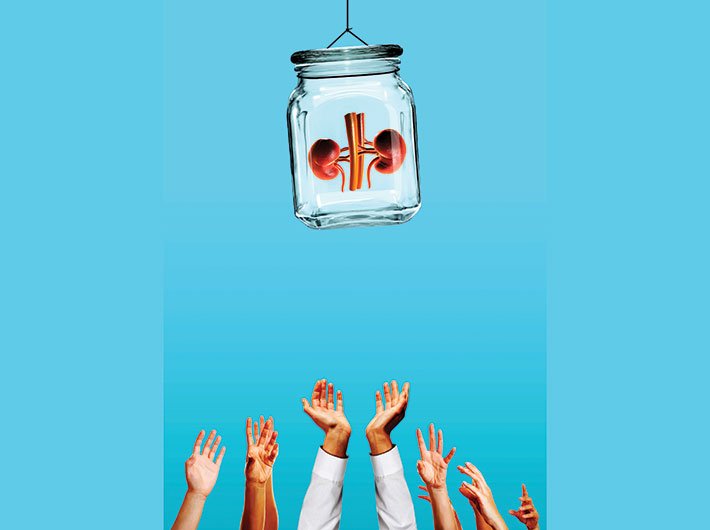

Kishan Kumar, who ran a small shop in Kanpur, died of kidney failure at 42. The cause, as in most cases, was progressive diabetes. With his meagre income, no medical insurance, and the responsibility of caring for a wife and three school-going children, he could afford dialysis, but not a kidney transplant – which would probably have saved his life. Thousands of Indians die such deaths for want of transplants. Having money is no guarantee of being able to arrange for a transplant either, for getting a donor (other than a relative) is almost impossible and cadaveric donations are difficult to organise.

India has some 61 million diabetics aged 20-79, and the number is rising yearly. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimates that by 2030, 8.4 percent of Indians (some 101.1 million) will be diabetic. Some experts call India the diabetes capital of the world. With hypertension and diabetes accounting for a majority of cases of organ failure, it is imperative for India to have an effective legal and policy framework in place to make transplants easy and affordable for those who need them. But there’s no hope this will happen soon.

At a loss

In his ‘Mann ki Baat’ radio talk to the nation in 2015, prime minister Narendra Modi urged people to donate their organs, which he said was the greatest donation they could make. But even if donors are available, the patient would have to go to private hospitals, where the procedure can cost from Rs 15 lakh to Rs 25 lakh and beyond. Of the 1,96,312 hospitals in India (India Brand Equity Foundation report), 14,379 are run by the government (National Health Profile, 2007). But according to the National Organ Transplant Organisation (NOTO), there are only 301 hospitals across the country, including government and private ones, where transplants can be carried out.

To get an idea of the dismal track record of government hospitals, one only need look at figures from AIIMS and the Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital, both in Delhi. AIIMS has performed only 141 cadaveric transplants to date, and Ram Manohar Lohia hospital only four. The six new AIIMS established over the last five years have not performed even one organ transplant, according to an RTI application. The PGI, Chandigarh, has performed 300 cadaver transplants of organs. Also, there aren’t enough transplant coordinators (point persons for matching donors to patients and doctors). An expert said there were four coordinators in government hospitals in a city like Mumbai – just not enough for a city of that size. And if this was the case with a big city, he said, you can imagine the situation for people living in towns and villages.

Since 77 percent of Indians do not have health insurance (according to a December 2017 report by KPMG and FICCI), they cannot think of going to private hospitals if they require a transplant. Of even those who have insurance, the majority have a Rs 5 lakh-10 lakh cover, not enough to pay for the cheapest of transplants, which would work out to Rs 15 lakh at least. Trouble is, many insurers set caps on payouts for transplants and other complicated procedures. Very few people buy insurance policies that give umbrella coverage for all diseases because premiums are exorbitant. “As a result, many people end up selling their land and other assets to get an organ transplant, but live miserable lives after the procedure, because they lose all their assets and much of their income after that goes into buying the expensive medicines they have to take all their lives. It is especially difficult when the patient is the only bread-winner of the family,” says Lalitha Raghuram, director of the Mohan Foundation, a voluntary group that among other activities supports patients requiring transplants. There are many NGOs, hospitals and trusts that help patients out with money or help them access funds from government. The internet has also spawned platforms like Milap and Ketto, which help generate funds through crowdsourcing. But all that is hardly enough.

In India, some kidney transplants happen in public hospitals, but most take place in private hospitals. However, liver transplants are almost exclusively conducted in private hospitals. This is for three reasons: a) the infrastructure simply does not exist at government hospitals, and that includes maintaining a sterile environment; b) they lack the specialists, who have mostly planted themselves in well-paying private hospitals; c) organising the logistics of transplants is expensive and government hospitals just don’t have the funds. As such there aren’t enough trained personnel to run transplant departments. Big private or corporate hospitals, however, gather and train the paramedical and non-medical ancillary staff required to create an effective transplant department. Obviously, patients end up having to shell out a lot of money – and there’s little help they get on this count. “There’s not much government support. Whatever support the government gives is not structured support. The support provided on the ground is by NGOs,” says Dr Darius Mirza, lead consultant for hepato-pancreatic & biliary surgery and transplants at Apollo Hospitals, Mumbai, who is also a founding member of Transplants: Foundation to Help the Poor, a non-profit.

Govt not doing enough

Across the world, transplants are mostly done at university hospitals or teaching hospitals. But this is not the case in India. “Teaching hospitals used to do well, but they stopped when things started becoming complex. In last ten years, it is corporate hospitals that led the way to anything new or anything different. The gap between the private and government/teaching hospitals in terms of skills is far greater than it ever was,” says Dr Mirza. He adds that if the government spruces up its hospitals – at least the teaching hospitals, attached to medical colleges – and appoints well-paid specialists to them, all segments of society could benefit from it and going to government hospitals would become the norm. “Then,” he says, “there will be much more trust that money will not decide who will get the treatment.”

Similarly, availability of organs and the infrastructure to co-ordinate the process efficiently needs to be improved at government facilities. Says Dr Harsh Johari, an adviser to NOTO on organ transplants, “It’s easy to say that 70,000 people die on the roads every year, so 1.5 lakh kidneys are available, so what else is needed? What remains unsaid is that if we had ambulances to pick them up in time, more than half of them wouldn’t die. Even if they are brought to hospital, many of our hospitals don’t have ventilators. We don’t have ventilators for living patients, leave alone the dying! If I’m a neurosurgeon and open someone’s skull, I’ll need a ventilator for that patient. I may not be bothered about cadaver donation, my commitment being to the living. So we don’t have the infrastructure, we do not have the trained nurses – at every step there is suspicion and answers to be made. Now the government is coming with some support; earlier, it used to be the rich man’s treatment. Now we have donations from the prime minister’s relief fund, the chief minister’s relief fund. We also try to help patients as much as we can.” He adds that the goal is to have transplant facilities at all medical college hospitals by 2020. Plus, government hospitals should take up transplant activity, while district hospitals should at least have arrangements for dialysis. “It’s easy to throw ideas about,” he says, “but it takes time to bring them to fruition.”

Dr Subhash Gupta, a liver transplant expert at Max Multispeciality Hospital, says, “Liver transplant is arduous, and requires 24x7 monitoring for a few days. This is difficult in government setups because of lack of infrastructure and incentives for doctors and staff.” Another expert adds that organ retrieval can come up at any time of the day or night and there’s no incentive for a government doctor to go beyond his duty hours to complete the task.

Changing, but not enough

The figures look tiny. Even so, organ donation has gone up five times, from O.16 persons per million population in 2012 to 0.80 persons per million in 2017. Last year, there were 800 organ donors in India, and 5,000 organs were harvested for transplants.

There’s more than just lack of awareness to blame for the low rates. Despite many campaigns, there is a significant gap between pledges to donate and actual donation. Says Dr Mirza, “I’ve worked for 20-25 years in the UK systems, and I don’t think events, walkathons are enough to raise awareness. Do you think political events where organ donations are pledged are enough? You probably have to work hard to educate the public and medical community also.” There are those who think incentives – non-financial, if need be – could promote organ donation. “We must think of incentivisation of the donor family in terms of the healthcare,” says Dr MC Mishra, former director of AIIMS, Delhi. He also advised that insurance must be regulated. Dr Subhash Gupta concurs, saying perhaps a CGHS health card could be issued to the immediate family of someone who donates organs on death. But there are those who believe organ donation is altruistic, and should be allowed to remain so.

The troubled path

According to the Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissue Act, 2011, cadaver transplants are allowed in case of brain death and most cases of brain death occur in accidents. The trouble is, doctors find it extremely difficult to make family members understand what brain death is. The question raised is: How can a person whose heart is beating and who is breathing be dead?

Another difficulty is the reluctance of doctors at public hospitals (where most accident cases are brought) to declare brain death.

Says Raghuram of Mohan Foundation, “When someone is in the ICU on a ventilator, doctors have to declare the person brain dead. When doctors don’t do so, how will the family know the person is brain dead and is a potential organ donor? The difficulty is more in the hospital domain than the public domain.” Quite often, there isn’t a neurosurgeon at the hospital, and doctors of other specialities refrain from declaring brain death. Now, with amendments to transplantation laws, it is not mandatory for a neurologist or neurosurgeon to be present: anaesthetists or intensive care specialists can head the board meant to declare brain death, provided they are not members of the transplant team.

Earlier, people were suspicious that brain deaths were being announced in order to harvest organs. Besides, there is an elaborate procedure to be followed. A cardiologist can certify cardiac death a day after he has finished his post-graduation requirements, but for brain death, to avoid error, it is required that two senior doctors not connected in any way to transplant teams make the declaration after eight specific tests.

But patients’ families resist. An RTI application revealed that the Ram Manohar Lohia hospital in Delhi declared 12 patients brain dead – but only verbally to relatives. Official written declaration was not made because all families refused organ donation. Some feel the law should make declaration of brain death mandatory. Tamil Nadu has such a law.

Dr R Anantharaman, of Frontier Lifeline Hospital, Chennai, says, “Smaller hospitals in Tier-2 towns, where quite a few people are taken after accidents, do not have specialists to declare brain deaths. So most of these hospitals don’t take the initiative for organ donation or transplant. Government is now looking at how small hospitals can be helped: maybe the patient can be transferred to a bigger hospital, or a specialist can come in and make the declaration.”

The second-level challenge occurs once a brain death has been declared. Says Raghuram, “We need trained transplant coordinators who will counsel and approach the family of the patient. Doctors are not going to ask about organ donation. These coordinators are trained to motivate the patient’s loved ones. Coordinator training takes place at several levels – the public, nurses, social workers, doctors and so on. We have trained some 1,600 coordinators across the country.”

Dr Anantharaman says one workable idea on which they have been working to get the centre and state governments to implement is an ‘organ donation clause’ in driving licences. “We’ve been working on the idea for 15 years, but now the government is looking at it seriously,” he says.

Also important, he says, is having infrastructure in place: databases accessible by all, trained personnel at government hospitals, organ retrieval teams, storage facilities and so on. Most important of all, he says, is the issue of trust. “What’s important is to reassure relatives of someone who has died that the organ goes to the right, deserving person,” he says. In Tamil Nadu, he says, there’s the Transplant Authority of Tamil Nadu (Transtan), with a doctor appointed by the state government as a secretary who ensures that donations are routed to the right recipient.

How others do it

Spain has for long been considered the model for organ donation. In May, 2017, the Indian government signed an MoU with Spain to facilitate bilateral cooperation in the field of organ and tissue procurement and transplantation. It is hoped that the exchange of knowledge will lead to improvement in organ transplant procedure here.

One of Spain’s key innovations is its “opt-out” system: every individual is a mandatory organ donor unless he or she opts out. Is the Spanish system suited to India? Says Dr Mirza, “The opt-out system requires a mature society. I don’t think India is ready for an opt-out system or it can ever be practised in India for a long time. We could not practise that in the UK, and we debated it for last 20 years. Only one part of the UK has adopted an opt-out. And that was about a year ago.”

Says Dr Johari, “Spain has a unique model. It is very small: you can have 30 or more Spains in India. They are educated people. They have one language and one religion. But perhaps if they have a referendum, more than 50 percent may say they won’t donate.”

In Iran, payment to a donor is allowed. Even then, only those who can afford to pay private hospital bills – and also pay the donor – are able to go for this option. Can India copy the Iranian system? “The model is very good if the system can be kept completely clean,” says Dr Mirza. “In western countries, people don’t need or expect to be rewarded in that way. And in India, the level of corruption is so high it will only provide one more avenue for corruption.” He says part of the reason it works in Iran is that it’s a police state. “The model might work in Singapore, but people in Singapore don’t need 1,000 dollars! It works in authoritarian settings where people are financially challenged.”

The Israelis have a different system. Priority in transplants is given by the government to those who have signed up as donors. “In Israel, you have to sign up as a donor and sign up as a recipient too. If I’m not ready to give, I shouldn’t expect state help when I have to receive. The law of averages says you are more likely to be a receiver than a giver. You are six times more likely to receive an organ than have the opportunity to give an organ. If it is good for everyone and there is 5:1 or 6:1 chances to become the organ receiver than organ donor,” says Dr Mirza.

TN’s success

Tamil Nadu is one of the leading states in having reforming organ donation and transplants. Where the India average is 0.8 donors per million, the state has a rate of 2.1 per million population (in 2016). In fact, Tamil Nadu is among the few states which introduced the deceased organ, transplantation programme in 1995. Brain death declaration is mandatory. The concept of non-transplant retrieval has increased donations. The state has a well-defined procedure of medico-legal cases in event of organ donation. Tamil Nadu has 218 transplant-licensed hospitals.

Dr Anatharaman speaks of how this came about: “When the Transplantaion of Organ Act (THOA) was introduced in 1994, on the initiative of renowned cardiologist Dr KM Cherian, a ‘brain dead’ law was enacted in Tamil Nadu. A network of four-five hospitals was created to share organs, and this model was later adopted by the state government. There was already a system in place, so they adopted it and generalised it for the whole state. If there’s any brain death, Transtan is to be notified. Under this cadaver transplant programme, it’s mandatory to register brain deaths with the authority.”

Says Raghuraman, “The most important thing is that the state government stepped in and ethical organ donation is happening here.” The rest of India could learn.

pragya@governancenow.com

(The article appears in the March 15, 2018 issue)